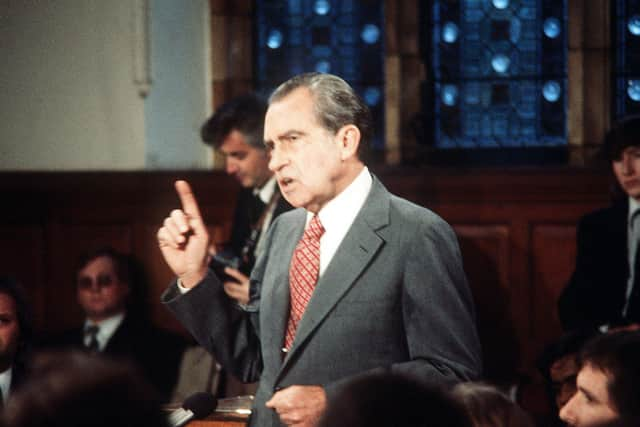

Watergate 50th anniversary: Nixon’s presidency was nothing short of a calamity

and live on Freeview channel 276

Nixon, not surprisingly, was in sombre mood, and in an attempt to lift his spirits, Kissinger assured him that history would judge him to be one of the great presidents. “That depends, Henry, on who writes the history,” Nixon replied.

He was right.

Most of what has been written about Richard Nixon since 1974 has not been favourable to its subject. Far from being considered one of the great presidents, he has often been judged to be one of the worst. The reason, of course, is Watergate, and to a much lesser degree, Vietnam – though the two are connected, as we will see.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWatergate is the filter through which the Nixon years are analysed, leading to an inevitably damning verdict. In his (taped) conversation with the president in March 1973, White House counsel John Dean described Watergate as a ‘cancer within ... the presidency’, but history’s verdict – so far – seems to be that Nixon himself was the cancer and that the presidency only survived when Nixon was removed – or rather, removed himself – from office on August 9 1974.

There is, however, another school of thought about why Nixon’s presidency ended in the way it did, one that fewer subscribe to but one that acknowledges the potential of the institution to mould and influence the office-holder, though we are conditioned to think of the office-holder shaping the institution.

Richard Nixon was the product of the ‘imperial presidency’ – a presidency seemingly without limits and without constraints; a presidency that had grown so powerful that the Constitution had become unbalanced. According to this line of reasoning, a rebalancing of the powers of governance was necessary to save the system. A reckoning had to happen – and that reckoning just happened to occur during Richard Nixon’s tenure of office. This is not to absolve Nixon of his wrongdoing – which essentially concerns his attempts to obstruct justice after 17 June 1972 – but rather to put Watergate in the context of post-war presidential history.

The focus remains on Watergate, however, and that puts any study of Richard Nixon itself in danger of becoming unbalanced. Watergate brought about the downfall of Nixon and dominated his second term in office, or what he served of that second term, but it does not explain why he came to power or, even more importantly, why he was re-elected in a landslide victory in November 1972.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWatergate continues to hold our attention because it marked such a dramatic fall after the successes of Nixon’s first four years in office. Ironically, it is precisely because Nixon de-escalated the Cold War, opened contact and dialogue with the People’s Republic of China and managed to extricate the US from its long and costly war in Southeast Asia without South Vietnam collapsing that we first and foremost remember Watergate – because it represented the most incredible contrast to Nixon’s achievements on the international stage.

Lord Longford gave his short biography of Nixon the subtitle ‘A Study in Extremes of Fortune’, and while it’s debatable how much the highs and lows of Nixon’s presidency had to do with fortune, there can be no argument that the gulf between the two was indeed extreme.

Elliot Richardson, the attorney-general who refused to carry out the president’s order to fire the Watergate Special Prosecutor in October 1973 and ended up being dismissed himself, once observed that the character defects that led to Nixon’s disgrace would not have been that hard to fix. However, he added, by doing so it is unlikely that Nixon would ever have made it to the presidency and the landmark foreign-policy triumphs of his first term.

It is relatively easy to draw a line from events and episodes in Richard Nixon’s earlier life and career through to the scandal and crisis of Watergate; it is much more difficult to determine where that line starts. For example, does the line reach right back to his youth and the trauma of his brothers’ deaths, especially that of his younger brother, scarring Nixon to the extent that he shut himself off from the world and other people, unwilling, and ultimately unable, to trust others and becoming himself distrusted?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOr are the seeds of Watergate to be found in the experiences of Nixon’s early political career, when he became an acceptable target for Democrats who could not lay a hand on the immensely popular Eisenhower? Or is the gestation period concentrated in the years 1960–62, when the presidency, he believed, was stolen by the Kennedys, when he delivered his ‘last press conference’, and when he came more and more to see his opponents not as adversaries but as enemies?

Perhaps Watergate was a product of Nixon’s White House years, when he and his small inner circle became increasingly isolated and embattled in the face of the anti-war movement on the streets, Democratic majorities in both Houses of Congress and a perceived fifth column operating within the wider administration and bent on sabotaging the president (principally through leaking classified information to the press).

An alternative explanation is to take a wider perspective in which Watergate becomes the endgame or endpoint of the imperial presidency, an institution already damaged and weakened by Vietnam and LBJ’s ‘credibility gap’. Richard Nixon’s actions brought the edifice crashing to the ground, but his presidency, in this reading, is only part of the story, though its most dramatic part.

Nixon’s predecessors since World War II had all engaged in borderline-legal if not illegal activities, had obfuscated and deliberately misled the American public, and had kept secrets – many, many secrets. Nixon’s secrets were uncovered, along with his lies, by his own taping system – and the price was the presidency.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo fully understand Watergate, however, we have to refocus yet again, and zero in on the period between June 1971 and August 1973. It was in June 1971 that The New York Times began publication of what became known as the ‘Pentagon Papers’, a classified and comprehensive study of why and how America had got involved in the war in Vietnam up to the end of the Johnson presidency.

Because the report did not encompass the Nixon presidency, the president was not initially perturbed by its publication; in fact, its criticism of the policies and actions of Kennedy and Johnson only confirmed what a difficult legacy they had bequeathed. However, Henry Kissinger persuaded the president that this major leak of classified information could have a negative impact on the highly secret and highly sensitive negotiations that the administration was engaged in with the USSR and China at this point, and that those responsible had to be uncovered.

So was born the Special Investigations Unit, better known as the ‘Plumbers’ (as their job was to plug ‘leaks’), the White House’s own team of investigators and intelligence-gatherers. Nixon might alternatively have called on the services of the CIA and/or the FBI to deal with the Pentagon Papers matter, but he did not trust either to carry out his wishes, convinced that they were dominated by Kennedy and Johnson sympathisers. The sense of being encircled by hostile forces that this mindset and action suggests would only deepen throughout the rest of Nixon’s presidency.

The Plumbers, comprising a number of ex-CIA and ex-FBI operatives, supervised initially by John Ehrichman, was an enterprise of dubious legality. Its first major operation, in September 1971 – the break-in at the office of Daniel Elsberg’s psychiatrist’s office to look for damning information about the man mainly responsible for the Pentagon Papers’ leak – was unquestionably illegal though it would only be uncovered much later during the Watergate investigations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was essentially this team, with a few changes in personnel, that would carry out the break-ins, during the second of which they would be apprehended by police, at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate office complex in Washington, DC, in June 1972. Their task was to gather information on the Democrats that would be useful to Nixon in the upcoming presidential election campaign by placing a wiretap on a number of telephones – though surprisingly, not that of the DNC chairman, Larry O’Brien.

It has never been proven that the president himself knew in advance about the Watergate operation, but within days of the burglars being caught he set in motion a cover-up to protect his administration and himself. This involved interfering with the FBI investigation, manipulation of the CIA, the payment of hush money to the burglars and their families, instructions to White House officials to commit perjury, and various other breaches of the law.

At first the plan seemed to work – Nixon secured a landslide re-election victory in November 1972 – but in the new year it began to unravel when one of the burglars decided to expose the cover-up. From that point, Nixon was fighting a losing battle to stay in office.

The televised Senate Watergate Committee hearings got the American public interested in the affair for the first time, and the discovery of the White House taping system in those hearings ensured that Nixon in the end would be condemned by his own words. When he lost the legal battle to retain control of the tapes under his claim of executive privilege – a battle that went all the way to the Supreme Court – he effectively lost the presidency.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRichard Nixon became the first American president to resign from office when he handed the presidency to Gerald Ford on August 9 1974. Had he not done so, he would have been impeached and most probably have been convicted by the Senate, with the Democrats in control of both Houses of Congress, Nixon simply did not have the numbers to survive.

And for Nixon and his supporters, this was what Watergate was really about in the end – party politics. He had left himself exposed by his own words and actions – his mistakes, as he called them; never wrongdoings – and his enemies used the power they had in Congress to, as he saw it, drive him from office and overturn the massive electoral mandate the American people had given him in November 1972.

As Nixon put it in his interview with David Frost some years later, “I gave them a sword. And they stuck it in. And they twisted it with relish. And, I guess, if I’d been in their position, I’d have done the same thing”.

If we assess Nixon as president using the criterion of comparing the state that the presidency was in when he inherited it in 1969 and the state of the office that he handed over to Gerald Ford, then his presidency was nothing short of a calamity. Arthur Schlesinger’s ‘imperial pres idency’ had crashed to the ground.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe process had begun with LBJ in Vietnam and the emerging credibility gap. This was the era when protestors began to burn the American flag – and when Richard Nixon in response began to wear an American flag lapel badge. Trust in the presidency began to erode because of Vietnam, under LBJ, and it was seriously damaged by Watergate, under Nixon. In the words of Theodore White – and the title he gave to his book about Watergate – Richard Nixon was guilty of a “breach of faith”: “The true crime of Richard Nixon was simple: he destroyed the myth that binds America together, and for this he was driven from power. The myth he broke was critical – that somewhere in American life there is at least one man who stands for law, the President. That faith surmounts all daily cynicism, all evidence or suspicion of wrongdoing by lesser leaders, all corruptions, all vulgarities, all the ugly compromises of daily striving and ambition. That faith holds that all men are equal before the law and protected by it; and that no matter how the faith may be betrayed elsewhere, at one particular point – the Presidency – justice will be done beyond prejudice, beyond rancour, beyond the possibility of a fix. It was that faith that Richard Nixon broke, betraying those who voted for him even more than those who voted against him.”

Rather than seeking to protect the presidency, Nixon believed that the presidency would protect him, and that miscalculation, based on a steady increase in presidential power during the Cold War, ultimately forced him to resign from office.

Some would argue that there was an upside to the way the Nixon presidency ended, in that the system – the US Constitution – proved that it worked. In particular, the Supreme Court remained ‘supreme’. It was a unanimous decision by the Supreme Court on July 24 1974 that effectively ended the Nixon presidency by ordering the release of the Watergate ‘smoking gun’ tape and other recordings.

The Justices held that not even the president was above the law, and it didn’t agree with Nixon’s claim of executive privilege. More important, the court said, were “the fundamental demands of due process of law in the fair administration of criminal justice”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe court’s curb on executive power would remain crucial in the future.

This all leaves us with the question of why, after his resignation and condemnation, Richard Nixon was not banished forever into outer darkness, why his presidency, and the man himself, continues to be a subject of debate?

The answer, of course – and this brings us full circle – is that there was more to Nixon than Watergate. Looking back on his life, Nixon wrote that he had “been on the highest mountains and in the deepest valleys”.

We have tended to focus on those valleys and have lost sight of the mountains.

About the author

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRonnie Hanna lectures in history in the adult education programmes at Queen’s University Belfast and Stranmillis College. He is happy to receive readers’ responses to this article, and can be contacted at [email protected]