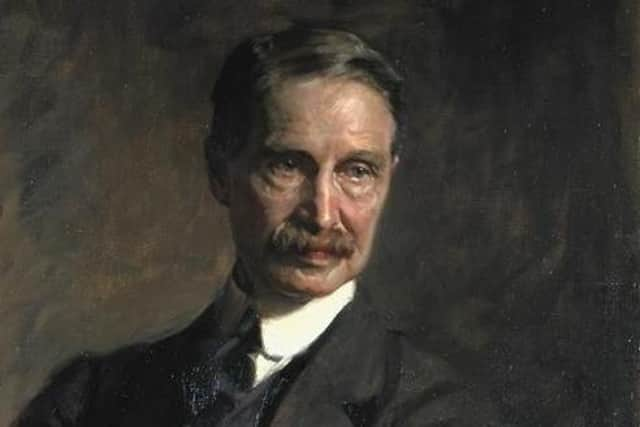

Andrew Bonar Law: Cancer robbed only Ulster-Scots PM of chance to make his mark

Although Law was born on September 16 1858 in Kingston, New Brunswick (one of the maritime provinces of modern Canada), and largely grew up in Glasgow and its environs, his father, the Rev James Law, was a Presbyterian minister from Coleraine. His brother, William, was a much-respected physician in Coleraine.

In 1877 the Rev James Law returned to live at Maddybenny, near Coleraine, and died there in 1882. During the last five years of his father’s life, despite being a notoriously bad sailor, the then Glasgow-based Law visited Ulster almost every weekend to see his father.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLaw knew Ulster and her people well. As a result, during the third Home Rule crisis in the years before the Great War, his sympathies were emphatically with Ulster Unionism. Ultimately, if Ulster was fairly treated, he would not stand in the way of the rest of Ireland having Home Rule.

As Lord Blake has noted, Law was a strange figure to become ‘the leader of the Party of Old England, the Party of the Anglican Church and the country squire, the Party of broad acres and hereditary titles’.

Law was more of an Ulster-Scot than he was ever Canadian or Scottish, was a Presbyterian, was steeped in commerce and industry and cared nothing for titles or honours. John Charmley has accurately described him as ‘the sort of leader the Conservatives would turn to because they could find no one else’.

In March 1921 Bonar Law stepped down from his first term as Conservative leader and was briefly replaced by Austen Chamberlain, the son of the great Joseph Chamberlain and the older half-brother of Neville Chamberlain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLord Blake described Austen as ‘kinder than his father, more likeable, more honourable, more high-minded and less effective ... he lacked that ultimate hardness without which men seldom reach supreme political power’.

Winston Churchill claimed Austen ‘always played the game, and he always lost it’. (Until William Hague, Austen was the only Conservative leader of the 20th century not to become prime minister.)

The real problem was that Austen was too wedded to the continuation of the Lloyd George coalition and the possibility of ‘fusion’ – the creation of a new centre party formed out of a merger with the Lloyd George Liberals – but the Conservative Party took a different view.

As the Carlton House meeting of October 19 1922 clearly demonstrated, the Conservative Party overwhelming rejected the continuation of the coalition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBonar Law told the meeting that he attached more significance to keeping the Conservative Party united than winning the next election and advised that the continuation of the Lloyd George coalition would result in what happened to the party after Peel repealed the Corn Laws in 1846.

Law explained that ‘the body that is cast off will slowly become the Conservative Party but it will take a generation before it gets back to the influence the party ought to have’.

After the Tory split in 1846 there wasn’t a Tory government with a parliamentary majority until Disraeli’s second administration in 1874.

As the Coalitionists in the Conservative Party (Austen Chamberlain, Arthur Balfour and Lord Birkenhead) accounted for most of the party’s talent, they imagined that Law would have great difficulty in constructing a new administration, but he did – even if Winston Churchill dismissed it as ‘a Cabinet of the second eleven’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn fairness, Law realised this and regarded one of his principal objectives to be to secure the return of ‘the Big Beasts’ to the fold. As already noted, Law had an acute appreciation of the importance of party unity.

Although the Cabinet was weak in debating power in the House of Commons, the Duke of Devonshire assured the Earl of Derby there was no need to worry because there was a clever lawyer called ‘Pig’ who could deal with all the difficult issues.

‘Pig’ was Sir Douglas Hogg, the attorney general, whose Ulster-Scots family roots were in Magheramorne, outside Larne. A formidable debater, he was always completely on top of his brief and persuasive.

One of his first tasks was to steer the constitution of the Irish Free State through the House of Commons. (He was to be the father and grandfather of Tory Cabinet ministers.)

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLaw’s premiership lasted only 209 days because he was diagnosed with inoperable throat cancer.

His premiership was too brief to evaluate properly and the problems – the intricacies of international debt, rising unemployment and a housing shortage – were too great to resolve in such a timescale.

But we can say that he was an effective chancellor of the Exchequer (1916-18), a formidable leader of the House of the Commons as Lord Privy Seal (1918-21) and a skilled leader of the opposition (1911-15).

As leader of the opposition before the First World War he was ‘a highly successful debater’ who ‘pulled no punches’ and mounted a direct frontal assault on Asquith’s Liberal government. He reinvigorated a dispirited Conservative Party, gave it purpose and direction and between 1911 and 1914 made 15 by-election gains and lost only two by-elections. He almost certainly would have won the general election due to take place in 1915 (which of course never happened because of the First World War).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs chancellor of the Exchequer, he financed the British war effort. Tom Jones, the Welsh assistant cabinet secretary and a former professor of economics at QUB, praised his series of war loans as ‘among the greatest achievements in the history of British finance’. In his 1917 budget Law proudly pointed out that the UK was unique in being able to raise 26% of its wartime expenditure out of revenue.

As Lord Privy Seal, he was highly successful, emollient (in contrast with his style between 1911 and 1914) and skilful in leading the House.

There is surely sufficient evidence to suggest Law could have been a very able prime minister.