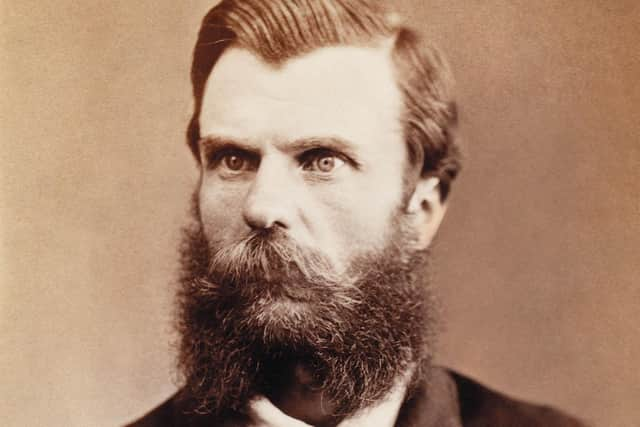

Andrew George Scott aka Captain Moonlite – the NI rector’s son who turned to life of crime in 19th century

As a young man, this Ulster-Scots equivalent of ‘the wild colonial boy’ was described as ‘dark, handsome, active and full of spirits … but known for impulsive acts of violence’.

Any consideration of Scott’s career requires a healthy measure of scepticism. If Scott is to be believed he studied engineering in London but his studies were swiftly terminated when he seduced the wife of a prominent businessman.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn Italy, while studying Roman aqueducts, he allegedly served with Giuseppe Garibaldi in il Risorgimento in 1860 and supposedly earned a personal note of commendation from Garibaldi. As an outlaw in Australia he was to wear a red shirt in Garibaldi’s honour.

In 1861 he moved to New Zealand with the intention of trying his luck in the Otago goldfields but the Maori Wars intervened. Scott served as an officer in the local militia, and fought at the battle of Oraku where he was wounded in both legs.

When he recovered, Scott went to America to prospect for gold in California but ended up by joining the Union Army in the American Civil War. He may have participated in William Tecumseh Sherman’s ‘March to the Sea’ in November and December 1864.

Returning to civilian life Scott worked as a consultant civil engineer in San Francisco before moving to Australia in early 1868.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere he ingratiated himself with Charles Perry, the Anglican Bishop of Melbourne, and became lay reader at the Church of the Holy Trinity, Bacchus Marsh, with the intention of entering the Anglican priesthood. At Holy Trinity he drew large congregations which enjoyed his colourful sermons enlivened by anecdotes from his military career. He was then sent to the gold mining town of Edgerton, near Ballarat, the centre of the Victorian gold rush of the 1850s and 1860s. There he grew bored of taking tea with respectable ladies, so much so that one night in May 1869 he donned a cloak and mask and robbed the local bank.

Scott forced Ludwig Julius Wilhelm Bruun, a young bank official whom he had befriended, to open the safe. Bruun described being robbed by a masked figure who forced him to sign a note absolving him of any role in the crime. The note read: ‘I hereby certify that L W Bruun has done everything within his power to withstand this intrusion and the taking of money which was done with firearms, Captain Moonlite, Sworn.’

Bruun subsequently claimed that the bank robber sounded like Scott but no gold was found in Scott’s possession. Scott retaliated by accusing Bruun and James Simpson, a local schoolteacher, of the crime. Bruun and Simpson became the prime suspects and Scott left for Sydney shortly afterwards. Both men were subsequently acquitted but lost their jobs.

Possessing impeccable manners and exuding considerable charm, Scott moved easily among the higher echelons of Sydney society for several months and lived lavishly off the proceeds of his crime. By the end of 1870 he began to pass worthless cheques. Arrested while trying to leave for Fiji aboard a fraudulently obtained yacht, he was sentenced to 12 months in jail. On his release in 1872 he was rearrested and charged with robbing the bank at Egerton.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInitially Scott conducted his own defence at his trial with considerable skill. However, relishing the experience too much and losing sight of the purpose of the exercise, he amused the courtroom by scoring points indiscriminately off witnesses, prosecuting counsel and the judge. Perhaps because of his impertinence, he was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in jail.

Scott was released from prison in March 1879 and embarked upon a new career as a penal reformer but was seriously irked that his campaign for prison reform was being regularly upstaged in the press by the exploits of ‘Ned’ Kelly.

Motivated by a combination of envy and admiration, Scott recruited a gang from among the friends he had made in jail and reverted to a life of crime as ‘Captain Moonlite’. Scott even invited ‘Ned’ Kelly to join forces with him but Kelly threatened to shoot Scott if he or his gang approached him.

Scott’s life of crime ended in a series of gun battles at Wantabadgery in November 1879. Scott and his gang had seized a sheep station, near Wagga in New South Wales, terrorising the employees and the family of the wealthy squatter. They also stole a substantial quantity of drink from the Australian Arms Hotel and took the residents of neighbouring properties hostage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFour police troopers eventually arrived, but Scott’s well-armed gang held them at bay for several hours until they retreated to a farmhouse owned by a man called McGlede. There the gang was surrounded by a more substantial force of police.

In the shootout at McGlede’s farm, a police trooper and a member of Scott’s gang were killed. James Nesbitt, a young man widely considered to be Scott’s lover, was mortally wounded, attempting to divert the police away from the house so that Scott could escape. When Scott saw Nesbitt shot, he was so distracted that McGlede was able to disarm him.

At his trial in Sydney, Scott in another bravura court appearance accepted total responsibility for everything which had happened and allowed the others to lay all the blame on him. He and another gang member were sentenced to death.

On the day of his hanging – January 20 1880 – Scott asked if journalists were to be present. On being told there would be none present, he went quietly to the gallows, wearing a ring woven from a lock of Nesbitt’s hair on his finger.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScott packed much into his 38 years. One journalist summed up Captain Moonlite’s career in terms which would have greatly flattered Scott’s ego: ‘Brave to the verge of recklessness, cool, clear-headed and sagacious and with a certain chivalrous dash … the beau ideal of the brigand chief’. The reader is under no obligation to accept this unduly sympathetic evaluation.