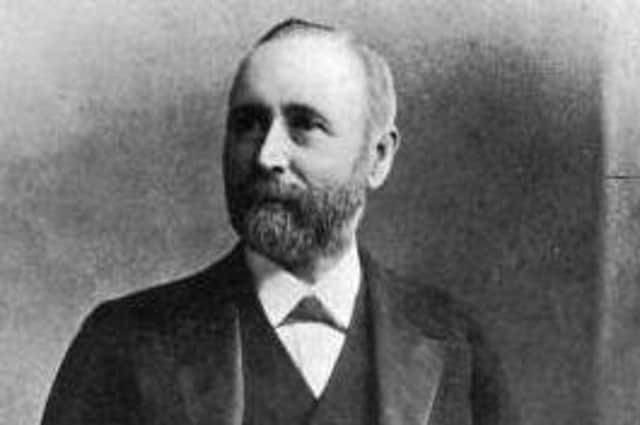

Apprentice who made Harland & Wolff the greatest shipyard in world

William James Pirrie was born on May 31 1847 in Quebec, Canada. He was the son of James Alexander and Eliza Pirrie (née Montgomery). Both parents were of Ulster-Scots ancestry. After his father died, mother and son returned to Ulster where the young Pirrie grew up in Conlig, Co Down.

At the age of 15 he entered Harland & Wolff as an apprentice-draughtsman. By the age of 27 he was a partner in Harland & Wolff and on Harland’s death he became chairman, a position which he retained until his death.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHarland contended that ‘Pirrie won his place in the firm by dint of merit alone, by character, perseverance and ability’.

Even at a very early stage he had almost exclusive control over the yard. Over the next 50 years under his leadership Harland & Wolff became the greatest shipyard in the world.

He travelled widely to keep abreast of the latest developments in naval architecture and marine engineering. He was at the forefront of the development of the diesel engine for marine propulsion. His career was contemporaneous with the development of the steel shipbuilding industry. He was ‘the creator of the big ship’ and for many years the largest passenger liners in the world came from his yards, notably the Olympic, the Britannic, and the Titanic.

Politically, he was rather more interesting and complex than either Edward Harland (Unionist MP for North Belfast, 1889-1895) or Gustav Wolff (Unionist MP for East Belfast, 1892-December 1910). At a dinner party on August 2 1886 Thomas MacKnight, the editor of the Northern Whig, asked Pirrie whether or not he would transfer Harland & Wolff to the Clyde in the event of Home Rule becoming law. He replied, ‘Most certainly this would be done’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt this stage Pirrie was a Liberal Unionist (a Liberal opposed Home Rule). However, in the first decade of the 20th century he reverted to Liberalism and became a Home Ruler. In 1896-7 he was lord mayor of Belfast and became the first freeman of the city.

In 1897 he was made a member of the Irish Privy Council. Harbouring parliamentary ambitions, in 1902 he wished to be the Unionist candidate in the South Belfast by-election of that year (occasioned by the death of the celebrated William Johnston of Ballykilbeg).

However, the Unionist Party selected another candidate. Out of pique, he assisted T H Sloan, the victorious Independent Unionist candidate and future founder of the Independent Orange Order, financially.

Pirrie wished to be the Unionist candidate in West Belfast in the general election of 1906 but failed to be selected. Again, out of pique, he ran Alexander Carlisle, the managing director of Harland & Wolff and his brother-in-law, as a spoiling independent unionist. Carlisle polled a derisory 153 votes but it was sufficient in a very tight contest to deprive the Unionist candidate of the seat and hand it to Joe Devlin, the Nationalist candidate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1906 Pirrie was raised to the peerage (for his political apostasy in the eyes of his political opponents) and was a prime mover in the establishment of the Ulster Liberal Association in April 1906. His support for Home Rule had no impact on the fervent unionism of the shipyard’s work force. In February 1912 he earned their contempt when he brought Winston Churchill, then a Liberal cabinet minister, to Belfast to speak in favour of Home Rule, and chaired the famous meeting in Celtic Park.

In 1907 Pirrie persuaded the White Star Line to order three great transatlantic liners which would put the White Star Line’s rivals and competitors out of business. The first would be named Olympic, the second Titanic and the third was originally to be called Gigantic. The Olympic was launched on October 20 1910. On May 31 1911 Olympic’s fitting-out was complete and the great liner, up until then the world’s biggest ship, steamed out of Belfast Lough.

However, a few hours earlier, Harland & Wolff launched the Titanic, 1,000 gross tons heavier than her sister ship.

The Gigantic was renamed the Britannic and was launched on February 26 1914. However, she was laid up for many months before being used as a hospital ship in 1915. In that role she struck a mine off the Greek island of Kea on November 21 1916.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn April 1912 Pirrie intended to travel aboard the Titanic on her maiden voyage but was prevented by illness. Had he done so he would be much better known today because he would have either drowned (like Captain Smith, Thomas Andrew or Colonel J J Astor, the Titanic’s captain, designer and richest passenger respectively) or he would have survived and have been universally reviled like J Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, who got away in one of the last lifeboats.

Between 1908 and 1914 Pirrie was pro-chancellor of Queen’s University, Belfast. In the years before the outbreak of the Great War he served as a member of the Committee on Irish Finance. In 1911 he became Lord Lieutenant of the City of Belfast.

During the war he was a member of the War Office Supply Board and in March 1918 he became Comptroller of Merchant shipbuilding, helping to replace British shipping lost to submarine warfare. He was also mainly responsible for introducing the idea of standardising ships, a principle that was adopted in Britain and the United States during Second World War.

In recognition of his war work and charity work, he became a viscount in 1921. He also became a member of the Senate, the upper chamber of the Northern Ireland Parliament.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy this stage he had abandoned both Liberalism and his support for Home Rule. His acute political antennae informed him that both represented the past rather than the future. The rebellion in Dublin in 1916 played a significant part in his return to Unionism.

He died at sea of pneumonia (on his return from a business trip to Latin America) on June 7 1924. The body was brought back to Belfast and was buried in the City Cemetery.