Bloody-minded Grant’s war of attrition forced Lee’s surrender in American Civil War

When President Lincoln brought Ulysses Grant east to confront Robert E Lee in March 1864, he was also given supreme command of all the Union’s armies.

Grant was aware of the challenge of confronting an enemy which enjoyed the advantage of interior lines of communication. Up to this stage the Confederacy was able to cope with widely separated Union thrusts by switching troops from one sector to another.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs Grant was in command of all the Union’s armies, including those commanded by William Tecumseh Sherman in the South and by Philip Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley, he sought to prevent this by putting all the Confederacy’s armies under simultaneous pressure.

Grant served in the field against Lee, supervising George Meade, who was still commander of the Army of the Potomac, and maintained a close eye on the Union campaign in its entirety.

Grant wasted no time in embarking on a campaign of attrition against Robert E Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The campaign lasted exactly a year and was punctuated by several extremely bloody battles, notably in The Wilderness (May 5-6 1864), and at Spotsylvania (May 8-19 1864) and Cold Harbor (June 1-12 1864).

The Wilderness was an area of dense woodland and it was here that the first direct clash between Grant and Lee occurred. Grant had never confronted a commander of such daring and flexibility while Lee had never faced such dogged determination from a Union general.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough vicious fighting resulted in a stalemate, Lee’s smaller force emerged best from the fighting and had succeeded in giving Grant’s army a bloody nose. On past form after such an encounter, the Union army would have retreated but not under Grant. On the evening of May 7 he ordered his army to continue their march south and ordered reinforcements. ‘I will take no backward step’ became one of Grant’s best-known sayings.

Spotsylvania was yet another brutal slogging match which could be viewed as a tactical draw. Lee inflicted heavy casualties on Grant’s army. Grant lost 18,000 men out of an army of 100,000. Lee probably lost 10,000 men out of his smaller army of 50,000. The difference was Grant could replace his losses but Lee could not.

Although Lee had managed to check Grant’s advance on Richmond twice – in The Wilderness and at Spotsylvania – in a fortnight, he told General Jubal: ‘We must destroy this army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River. If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.’ The accuracy of Lee’s analysis cannot be faulted.

Cold Harbor was one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. In an episode which invites comparison with Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg, Grant threw his men across open ground against Lee’s carefully prepared defensive positions with devastating losses. At dawn (4.30 am) on June 3, three Union corps attacked the Confederate works at the southern end of the line at Cold Harbor and sustained between 6,000 and 7,000 casualties in approximately an hour. By noon the attack was called off.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Union soldiers who participated in the attack had no illusions about its outcome and their prospects of survival. Before the battle a member of Grant’s staff saw them pinning pieces of paper to their coats with their names and addresses so that their bodies would not go unidentified.

The youthful General Emory Upton, who had distinguished himself by his carefully planned attacks at Rappahannock Station and Spotsylvania, was ‘disgusted’: ‘Our men have … been foolishly and wantonly sacrificed … thousands of lives might have been spared by the exercise of a little skill.’

Grant briefly became ‘Butcher Grant’. In his personal memoirs, one of the classics of military literature, Grant wrote: ‘I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made ... No advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained.’ Grant lost between 10,000 and 13,000 men in 12 days.

Despite horrendous casualties, Grant’s year-long campaign was a strategic success for the Union. By engaging Lee’s forces and not allowing them to escape, Grant forced Lee into a siege at Petersburg in just over eight weeks and inflicted proportionately higher losses on Lee’s army, although not numerically. Lee’s losses, although lower in absolute numbers, were higher in percentage terms (over 50%) than Grant’s (about 45%).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

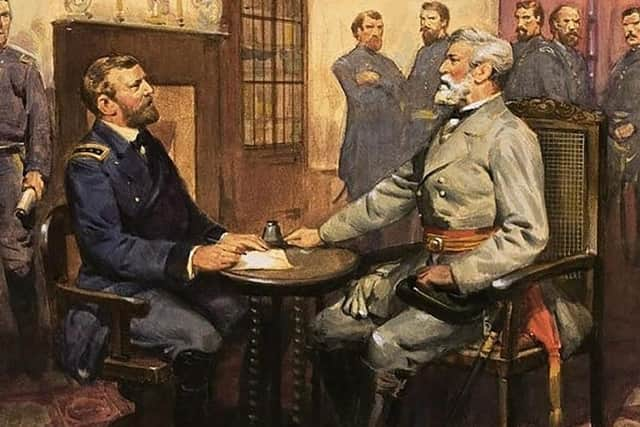

Hide AdGrant’s war of attrition succeeded in grinding down the Confederates. On the afternoon of April 9 1865 Robert E Lee surrendered the remnants of the once proud Army of Northern Virginia to Grant at Appomattox. Recognising the importance of securing national reconciliation, Grant offered his defeated opponents generous peace terms. In doing so, Grant was complying with President Lincoln’s wishes as expressed to Grant and W T Sherman on March 28.

Grant told Lee that his officers and men could go home ‘not to be disturbed by US authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside’, a formula which guaranteed former Confederate soldiers immunity from prosecution for treason.

Grant agreed, at Lee’s request, that his men could retain both their horses and mules to enable them ‘to put in a crop to carry themselves and their families through the next winter’.

Lee responded: ‘This will have the best possible effect upon the men and do much toward conciliating our people.’ Finally, Grant sent three days’ rations for 25,000 men to Lee’s famished army. As James M McPherson has observed: ‘This perhaps did something to ease both the psychological as well as the physical pain of Lee’s soldiers.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBefore the Civil War Shelby Foote has pointed out that Americans spoke of their country in terms of ‘the United States are …’. Significantly, postbellum usage became ‘the United States is …’. Although not grammatically correct, this was indicative of a shift away from the individual states and towards a renewed emphasis on the Union, which Lincoln politically and Grant militarily had secured and preserved.