Bloody Sunday 1920 was barely a bump on road to Irish settlement

On November 9, 1920 in his Mansion House speech Prime Minister Lloyd George famously claimed to have ‘murder by the throat’ but he also said: ‘We are offering Ireland not subjection but equality, not servitude but partnership.’

This was an explicity twin-track strategy: military pressure to bring Sinn Fein to the negotiating table and holding out the prospect of generosity in the negotiations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was an appreciation in London and Dublin Castle that many republicans would happily accept a ceasefire, negotiations and dominion status. It was Canadian historian Peter Hart’s assessment (in ‘Mick: the Real Michael Collins’) that Collins would have been very happy with a ceasefire beginning as early as December 1920.

Signals were exchanged and channels of communication were opened up. Patrick Moylett, a republican businessman close to Arthur Griffith, the founder of Sinn Fein, was the first conduit. In December, at the suggestion of Joe Devlin MP, Archbishop Clune of Perth (in Western Australia), became another intermediary. The events of Sunday November 21 1920 scarcely got in the way.

The IRA’s riposte to Lloyd George’s Mansion House speech was to be a day of spectaculars: the targeting and killing of intelligence officers (the self-styled ‘hush-hush men’) in Dublin and attacks on Liverpool docks and warehouses, power plants in Manchester and London timber yards.

The aim was to relieve the pressure on the IRA by killing the ‘hush-hush men’ who were proving too successful in identifying the terrorists and hampering their activities on one hand and to demonstrate on the other that the IRA remained in business. Ironically, the spectaculars in Manchester and London had to be aborted because the IRA’s plans had been captured by the authorities in a raid.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

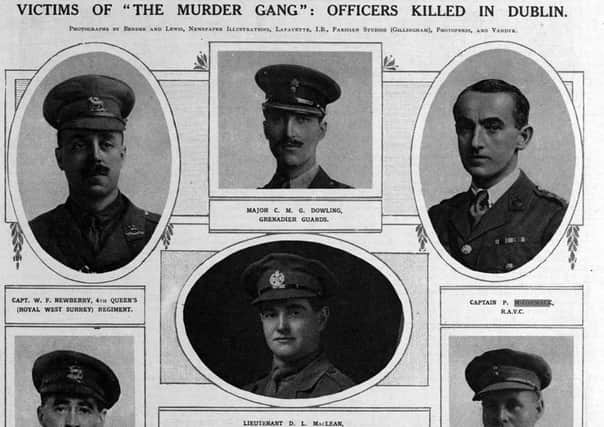

Hide AdOn Sunday morning of November 21 Michael Collins’ squad visited eight addresses, the homes of those who the Dublin brigade of the IRA believed to be the ‘hush-hush men’, in the centre of Dublin which left 14 men dead, one mortally wounded and five wounded but who survived. Jane Leonard provides impressively researched biographical detail and analysis of the victims in an essay in David Fitzpatrick (ed.) ‘Terror in Ireland 1916-1923’.

Twelve of the 15 were members of crown forces: eight were serving army officers, a GHQ staff officer on secondment from the Admiralty, and three were policemen. Two were civilians and a third defies ‘confident categorisation’. Of the nine army officers, six were engaged in intelligence operations and two were court-martial officers. The GHQ staff officer was not involved with military intelligence. At least one man – an Irish vet in Dublin to purchase mules – was wrongly identified.

As far as republicans are concerned, ‘Bloody Sunday’ refers solely to the events of the afternoon of November 21 when Auxiliaries were sent to a GAA match at Croke Park to apprehend IRA men on the run, or even some of those who had been involved in the morning’s shootings.

The plan was to surround the ground as soon as the match began. Armoured cars were deployed at the main entrance. Troops would guard all the exits and the railway line behind the ground. Fifteen minutes before the end of the match an officer would announce that all males leaving the ground would be stopped and searched. Anyone trying leave by any route other than the official exits would be shot.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThings did not go according to plan. Ten minutes into the match shooting broke out. Who fired first has never been conclusively proven (and never will be). It is perfectly possible that it was an IRA man attending the match. Dozens of IRA weapons were found abandoned at Croke Park afterwards. Fairly or unfairly, the Auxiliaries are usually saddled with the responsibility. Twelve people were killed and many more wounded. One of those killed was a member of the Tipperary team and an IRA officer.

Three more men died in Dublin before the end of the day: Richard McKee, Peter Clancy and Conor Clune. They had been arrested the previous evening and were allegedly shot while attempting to escape from Dublin Castle.

McKee was the commander of the Dublin Brigade of the IRA and Clancy was his second-in-command. Clune is sometimes regarded as a civilian but a memorial plaque in Dublin Castle describes him as Volunteer Clune. Of greater significance, his uncle was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Perth.

The events at Croke Park were an unmitigated public relations disaster, consolidating support for Sinn Fein.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe impact of the shootings in the morning has been greatly exaggerated. The IRA had not ‘blinded the British secret service in Dublin’. By the spring of 1921, as Collins was fully aware, the authorities had rebuilt an even better intelligence organisation in Dublin which was putting the IRA under severe pressure.

According to Liam Tobin, an IRA intelligence officer, the deaths of McKee and Clancy ‘knocked all the good out of it [the morning’s events] … we had no sense of jubilation as the enemy had evened up on us’. Lloyd George dismissed events in Dublin as ‘tragic’ but ‘of no importance’, adding: ‘These men were soldiers and took a soldier’s risk.’

Patrick Moylett assumed events had derailed the government’s peace overtures only to be told: ‘Not at all.’ Moylett proved indiscreet, to Collins’ disgust, and Archbishop Clune’s efforts did not produce immediate success but events moved, albeit slowly and almost imperceptibly, in the direction Lloyd George envisaged because Collins was seriously interested in peace.

In December 1920 Collins had told Arthur Griffith: ‘It is too much to expect that Irish physical force could combat successfully English physical force for any length of time if the directors of the latter could get a free hand for ruthlessness’ (which Collins feared would become the case). Other IRA leaders too came to realise they could not sustain their campaign indefinitely. A truce came into operation on July 11 1921, and negotiations resulted in the Anglo-Irish treaty of December 6 1921 and the establishment of the Irish Free State, a polity with dominion status, in 1922.