Charles III coronation: Shrouded in myth, the Stone of Scone will be at centre of ceremony

Although it could be dismissed as only a block of red sandstone, weighing 336lb (24 stone), it is regarded as a sacred and ancient symbol of Scotland’s monarchy and has played an integral part in coronations for centuries.

Its origins are shrouded in myth and legend but, whatever the truth, it is part of our national heritage.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLegend has it that it was the pillow used by Jacob in Genesis 28 when he dreamed of a ladder reaching up to heaven.

Legend also has it that the prophet Jeremiah arrived in Ireland, several years after the capture of Jerusalem by Babylonians, accompanied by Tephi, the daughter of King Zedekiah, the last king of Judah, and heiress to the Davidic throne. He also brought with him a stone subsequently named Lia-Fáil (the Stone of Destiny in Irish).

Tephi married Eochaidh, a Milesian-Zarahite prince of Ireland. This union preserved the line of Solomon and the Davidic throne.

The Lia-Fáil became the coronation stone which was used at Tara for inaugurating the High Kings of Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Ulster-Scots take on the Stone of Destiny focuses on the Ulster-Scottish kingdom of Dalriada and Fergus Mór (Fergus the Great), its first king after whom Carrickfergus is named.

Around 503 Fergus supposedly took the Stone of Destiny (Lia-Fáil) as his coronation stone to Argyll where he was crowned on it, according to ‘Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland’ (Original Chronicle of Scotland) by Andrew of Wyntoun (c. 1350-c. 1425).

In 841 Kenneth MacAlpin, a descendant of Fergus Mór and the first king of Dalriada and the Picts, is supposed to have taken the stone from Iona to Scone Abbey in Perthshire.

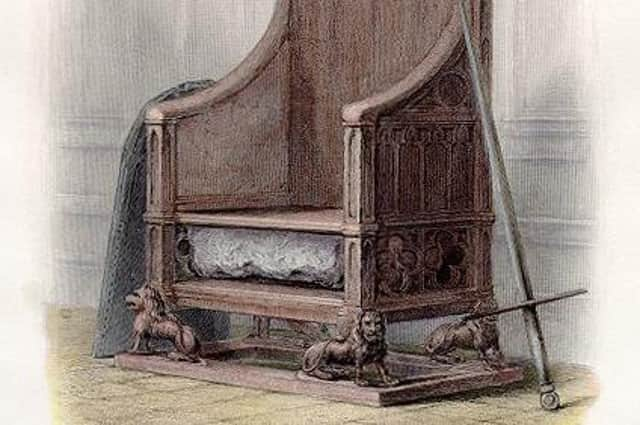

For five centuries, the Stone was kept in the abbey church there and only taken out to the Moot Hill for enthronements. At first it may simply have been covered with embroidered cloth for the king to sit on. Later it may have been incorporated in a wooden throne.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1296, when King Edward I invaded Scotland, he removed the stone and had it incorporated in a new throne at Westminster Abbey, known as King Edward's Chair – which is said to be the oldest piece of furniture in the United Kingdom to retain its original function.

(Some believe that the stone taken to London by Edward was a fake because the abbot at Scone concealed the real Stone in the River Tay or buried it elsewhere. It is alleged that descriptions of the Stone of Scone do not match the present stone.)

For 700 years, it has been used in the coronation ceremonies of most British monarchs. In the 17th century the historian John Speed described the stone in Westminster Abbey used in the coronation of James VI & I in July 1603 as ‘Saxum Jacobi’ (the Stone of Jacob).

By the terms of the Treaty of Northampton, the English agreed to return the stone to Scotland in 1328 but rioters prevented its removal from Westminster Abbey.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThereafter, the stone’s history has been uneventful. In 1657 Oliver Cromwell removed it to Westminster Hall for his investiture as Lord Protector.

It may have been damaged in 1914 when suffragettes hung a small bomb on the Chair.

During the Second World War it was secretly buried within Westminster Abbey to prevent it falling into the hands of the Germans.

Apart from the Dean of Westminster and Charles Peers, the Surveyor of the Fabric of Westminster Abbey, very few people knew of its hiding place.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdConcern that the secret could be lost if all these people were killed during the war (by no means an improbable scenario), Peers drew three maps showing the hiding place.

Two were sent in sealed envelopes to Canada, one to the Canadian prime minister who deposited it in the Bank of Canada’s vault in Ottawa. The other went to the lieutenant governor of Ontario who stored his envelope in the Bank of Montreal in Toronto.

Once Peers had received word that the envelopes had been received in Canada, Peers destroyed the third map.

In the 1950s the SNP commanded derisory electoral support but on Christmas Eve 1950 a group of four Scottish nationalists pulled off a stunning public relations coup by breaking into Westminster Abbey and removing the stone, breaking it into two when they dropped it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCompton Mackenzie’s novel ‘The North Wind of Love’ (1944) probably inspired the stunt. Mackenzie was a life-long Scottish nationalist and a co-founder of the National Party of Scotland, a precursor of the SNP.

The stone disappeared without trace for four months but was found in the ruins of Arbroath Abbey, where the Declaration of Arbroath was drawn up in 1320, on April 11 1951.

The stone – again with some doubts as to whether it was the original – was returned to London and was in place for the coronation of the Queen in 1953.

In 1996, when the SNP had become a more significant electoral force, then prime minister John Major unexpectedly announced in Parliament that the stone would be returned to Scotland on the understanding that it could be ‘borrowed’ for future coronations. (The Dean of Westminster was only informed 48 hours earlier.)

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the 700th anniversary of the stone’s removal from Scotland, Prince Andrew handed it over to Historic Environment Scotland, the custodians of Edinburgh Castle, where it was displayed with the ‘Honours of Scotland’ (the Scottish Crown Jewels) in the Crown Room.

The then moderator of the Church of Scotland hailed the stone’s return as ‘a substantial landmark’.

Four days after Queen Elizabeth II’s death, Historic Environment Scotland announced that it would be conveyed to Westminster for the coronation of Charles III.

In 2024 the stone is to find a new home in Perth City Hall, which is only two or three miles from Scone.