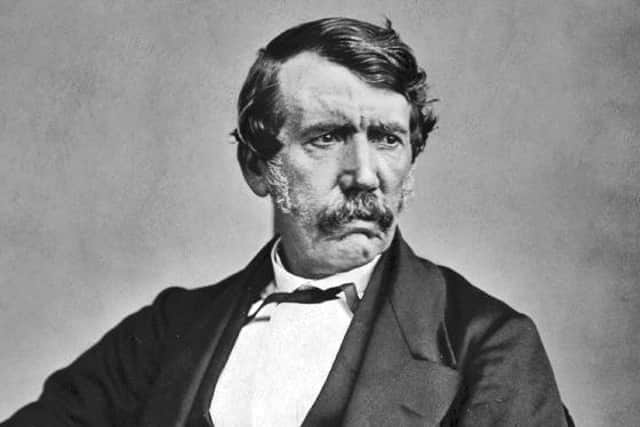

Dr Livingstone I presume? Iconic meeting was 150 years ago

Dr Livingstone, I presume?’ One of the most famous encounters in history occurred 150 years ago on November 10 1871 when Henry Morton Stanley, the Welsh-born journalist, finally located the missing Scottish missionary and explorer Dr David Livingstone in Ujiji, near Lake Tanganyika.

In the late 1860s, while searching for the source of the Nile and compiling facts on the slave trade (conducted by Arabs), Livingstone lost contact with the outside world for six years. In 1869 the New York Herald sent Stanley to find him. Stanley allegedly greeted Livingstone with the now famous words ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’ Stanley’s famous words – perhaps more appropriate to an encounter between two gentlemen meeting for the first time in a London club – may well be a fabrication but it scarcely matters. In 1872 Stanley published a book entitled ‘How I found Livingstone’ which Florence Nightingale scathingly dismissed ‘as the very worst book on the very best subject I ever saw in my life’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdH M Stanley was born illegitimate in 1841 in Denbigh in north Wales and grew up in the Asaph Union Workhouse. There was a time when Stanley’s achievements (finding Dr Livingstone, his exploration of central Africa and his search for the of the source of the Nile) and in overcoming the disadvantages of his birth and upbringing were much admired. These days the focus tends to be on less admirable episodes in his life such as his (probably reluctant) service in the Confederate Army during the US Civil War and the work he undertook for King Leopold II of the Belgians in the Congo basin.

David Livingstone too was born in humble circumstances. He was born in a single-room tenement in Blantyre, Lanarkshire, a generation earlier in 1813. Aged 10, he went to work in the local cotton mill. He studied at night school and the Anderson Medical School in Glasgow where he trained as a doctor. A Congregationalist, he was accepted for service by the London Missionary Society as a medical missionary and was sent to southern Africa.

He viewed his mission spreading the gospel to the African interior and ending the slave trade (an evil which was simply impossible to exaggerate) but he also inadvertently became an explorer.

In 1849 and 1851 he travelled across the Kalahari Desert. Between 1852 and 1856 he searched for and found a route from the Upper Zambesi to the Indian Ocean.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe explored the southern and eastern regions of the African continent between 1858 and 1864.

One of his great achievements was to dispel the myth that the African interior was arid desert inhabited by savages. On the contrary, it was a land ripe for cultivation, settlement and economic development.

By settlement, Livingstone meant settlements of dedicated European Christians who would live among the Africans assisting them to devise ways of living that did not involve slavery.

The Zambesi River, he thought, would greatly facilitate trade. In this he was mistaken because the river is frequently interrupted by rapids which have unfortunately prevented it from becoming a major transportation route.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe embarked upon his final and longest mission in 1866 (during which he disappeared from the view of the outside world).

Although often described as ‘Africa’s greatest missionary’, it is possible that he converted only one African: Sechele, who was the chief of the Kwena people in Botswana.

Livingstone had great difficulty in converting Africans to Christianity to his satisfaction. Africans were not impressed by his unwillingness to demand rain of his God like their rainmakers, who said that they could. Polygamy was another problem. Where Livingstone’s teaching was found to be at variance with his African heritage, Sechele, tended to opt for his native culture.

Nevertheless, Sechele proved to be an important convert because he remained faithful to Christianity (in his own way), introducing missionaries to surrounding tribes and succeeding in the conversion of almost the entire Kwena people. Neil Parsons of the University of Botswana has concluded that Sechele did more to spread Christianity in 19th-century southern Africa than virtually any single European missionary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe sincerity of Livingstone’s Christian faith is not in serious doubt. In one entry in his journal, he wrote: ‘I place no value on anything I have or may possess, except in relation to the kingdom of Christ. If anything will advance the interests of the kingdom, it shall be given away or kept, only as by giving or keeping it, I shall promote the glory of Him to whom I owe all my hopes in time and eternity’.

Whatever Livingstone’s shortcomings as a missionary, he surely deserves most of the credit for the expansion of missions to central Africa in the 1870s and 1880s and raising the profile of overseas missions in general.

Livingstone treated Africans with respect, and this was fully reciprocated. This too was an important legacy. He believed Africans were no better or no worse than Europeans. What condemned them to poverty and barbarism were basically defective social and economic institutions, which could be improved through the joint forces of commerce and Christianity.

Twentieth-century African nationalists admired Livingstone for his opposition to white rule, his humanitarianism, and his commitment to the equality of mankind. (Livingstone was an ardent admirer of the equalitarianism of Burns.) Kenneth Kuanda, the first president of Zambia, even described Livingstone (somewhat incongruously) as ‘the first freedom fighter’. On the centenary of Livingstone’s death in 1973 34 African countries issued stamps in his honour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite the animosity of many Africans towards figures such as Cecil Rhodes, Livingstone continues to be held in high esteem.

Few would dream of toppling statues of Livingstone. Indeed, a new statue of Livingstone was erected on the Zambian side of the Victoria Falls in 2005. (Livingstone was probably the first European to view the falls – on November 16 1855.)

Rhodesia is now Zimbabwe, but the cities of Livingstone in Zambia and Livingstonia in Malawi happily retain these names with pride. Blantyre, formerly the capital of Malawi and still the seat of the judiciary, is named after Livingstone’s birthplace.