Edith, Marchioness of Londonderry, and Ramsay MacDonald: the landed Tory lady and the Labour PM

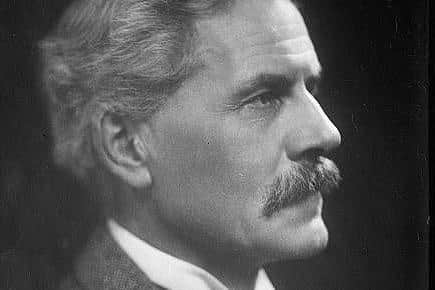

He became a socialist at the age of 19 and spent almost 50 years promoting his vision of parliamentary socialism.

Disproportionately responsible for shaping the thinking of the early Labour Party, he succeeded in transforming it from a weak and deferential trade union pressure group into the main left-wing party in the UK and led the first Labour government which took office in January 1924. He deserves to be regarded as a ‘pivotal’ figure in modern British history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBorn on December 3 1878, Edith Chaplin came from the very opposite end of the class or socio-economic spectrum. She was the daughter of Henry Chaplin, a Conservative MP and landowner, and Lady Florence Sutherland-Leveson-Gower. As a result of the early death of her mother in October 1881, she grew up in Dunrobin Castle, home of her maternal grandparents, the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland, the largest landowners in the British Isles.

At the age of 21, Edith Chaplin married Viscount Castlereagh, the eldest son of the 6th Marquess of Londonderry and one of the most eligible bachelors of the day.

When Edith’s father-in-law died in 1915, she became the Marchioness of Londonderry and the chatelaine of several large houses, most notably Londonderry House in Mayfair and Mount Stewart in Co Down. The Londonderrys also owned Seaham Hall and Wynyard Park (both in Co Durham) and Plas Machynlleth in Wales.

Despite being born in England, Edith, by virtue of her Scottish ancestry and upbringing, her marriage to Viscount Castlereagh and her long residency at Mount Stewart, may be regarded as an Ulster-Scot.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEdith was well known as a leading political and society hostess, especially at Londonderry House, Park Lane, London, where she established an exclusive dining club, ‘The Ark’, which included, among many others, every British prime minister of the 1930s and the future Edward VIII and George VI. On the strength of these connections, she was formidably well informed.

MacDonald was widowed in 1911 at the age of 45. He had warm relationships with several upper class women – Lady Margaret Sackville, Mrs Molly Hamilton and Cecily Gordon-Cumming – who provided him with a degree of emotional support, even if these relationships could not entirely fill the void in his life. As Diane Urquhart explains in ‘The Ladies of Londonderry: Women and Political Patronage’ (London 2007), ‘MacDonald’s loneliness holds the key to understanding his friendship with Edith Londonderry’.

They first met at a dinner in Buckingham Palace, shortly after MacDonald became prime minister. At this point Edith ‘detested’ MacDonald’s views on Russia and ‘disliked’ what she had heard of him, not least because of his pacifism during the Great War. For his part, MacDonald found it difficult ‘not to hate Conservatives deeply’ and had ‘an ill-concealed distaste for unionism’.

Despite being politically poles apart, they discovered a shared interest in the Scottish Highlands and Gaelic myths and folklore. (Edith was a Highlander, descended on her mother’s side, from the Mackenzies who had been Jacobites in 1745.) They also found that they enjoyed each other’s company and had a similar sense of humour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough warned that Edith was a ‘a dangerous woman’ – probably by Beatrice Webb – MacDonald was undeterred.

Within ‘The Ark’, Edith was ‘Circe’, an enchantress in Greek mythology, and MacDonald became ‘Hamish the Hart’. The relationship became much closer during the second Labour government (1929-31) than the first and after MacDonald’s breach with the Labour Party in 1931 it became closer still.

In this period David Marquand, MacDonald’s biographer, contends – based on her surviving correspondence – that she provided him with ‘a good deal of moral and emotional support at a time when he badly needed them’. His letters, again according to Marquand, make clear that ‘he became more dependent on her’.

Diane Urquhart acknowledges their close friendship had ‘serious political implications’ right up until MacDonald’s death in 1937.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen her husband was appointed secretary of state for air (1931–5), he attributed his appointment to his wife's friendship with MacDonald, who was then prime minister. MacDonald formed a National Government with Conservatives and Liberals in 1931 in response to the financial crisis. Edith was credited with being its ‘mother’ and was the object of serious and widespread criticism within the Labour Party.

According to the Duke of Sutherland, Edith’s cousin, she had first floated the idea of a national government on a visit to Chequers in November 1930.

On January 16 1930 Tom Jones, a senior civil servant and former professor of economics at QUB, noted in his diary the increasing social and political fusion between the Londonderrys and MacDonald as well as the unease that it caused.

In February 1930 the Daily Express observed: ‘A Socialist Prime Minister sat amicably with the greatest Tory hostess of her generation … The lion had indeed lain down with the lamb’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMacDonald defended his infatuation with the Marchioness by claiming their relationship was 'spiritual', prompting one irate Labour activist to observe, 'I thought the bugger was daft'.

Little wonder MacDonald was vilified by the Labour Party as a turncoat who consorted with the enemy and drove the Labour Party to its nadir in the general election of 1931 when it was reduced to a rump of 52 MPs.

In the 1930s Edith’s relationship with MacDonald was sufficiently close to provoke scurrilous gossip. Lady Rose Lauritzen, Edith’s granddaughter, has repudiated the idea they were lovers. She insists – almost certainly correctly –their relationship was purely platonic.

Ramsay McDonald was not the only Labour prime minister over whom an un-elected woman has exerted huge influence. Marcia Williams (subsequently raised to the peerage as Lady Falkender) was Harold Wilson’s political secretary. Unlike Edith and MacDonald, Wilson and Williams were lovers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to Joe Haines, Wilson’s press secretary, Wilson lived in fear and dread of her ‘tantrums, tirades and tyranny’. Haines even blamed Williams for Wilson’s early political demise in 1976 and believes that ‘on a scale of evil no one approached Marcia’.

Observing the strange dynamic between Wilson and Williams, Bernard Donoughue, Wilson’s policy advisor, concluded in his diary: ‘I get the feeling everything [Wilson] does in politics is to please her.’