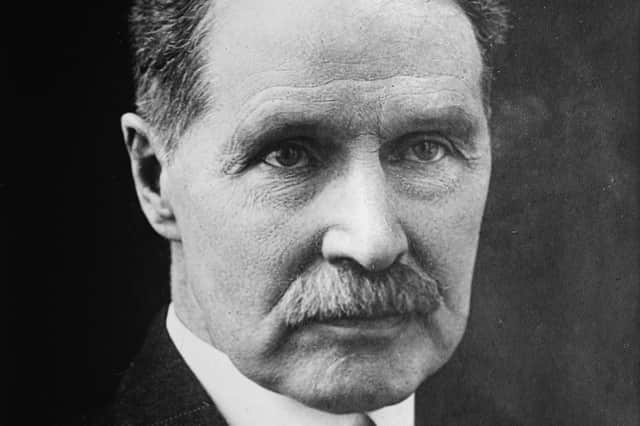

Gordon Lucy: Bonar Law, Ulster-Scots PM with a career rich in ironies

Although Law was born on September 16 1858 in Kingston, New Brunswick (one of the maritime provinces of modern Canada), and largely grew up in Glasgow and its environs, his father, the Rev James Law, was a Presbyterian minister from Coleraine. His brother, William, was a much-respected physician in Coleraine.

In 1877 the Rev James Law returned to live at Maddybenny, near Coleraine, and died there in 1882. During the last five years of his father’s life, despite being a notoriously bad sailor, the then Glasgow-based Law visited Ulster almost every weekend to see his father.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLaw knew Ulster and her people well. As a result, during the third Home Rule crisis in the years before the Great War, his sympathies were emphatically with Ulster Unionism. Ultimately, if Ulster was fairly treated, he would not stand in the way of the rest of Ireland having Home Rule.

For the connoisseur of irony, Law’s career is rich in ironies.

No Conservative leader in the 20th century waited so long for the premiership yet occupied the office for less time – 209 days.

His short tenure is no reflection on his ability. Ill-health alone curtailed his occupancy of 10 Downing Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLaw is the only Conservative leader to have returned to the party leadership having relinquished it – as we will see.

As a man who devoted so much of his time and energy into keeping the Conservative Party united, it is ironic that he should have secured the premiership as the result of a party split.

On October 19 1922 Conservative MPs met at the Carlton Club to discuss the continuation of the party’s coalition with Lloyd George’s Liberal Party.

‘The big beasts’ of the Conservative Party – Austen Chamberlain, Balfour and Birkenhead – favoured the continuation of the arrangement. Lord Birkenhead was contemptuous of those who thought otherwise.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Conservative Party’s ‘big beasts’ believed a continuation of the coalition was necessary to oppose the rise of the Labour Party. Some were already thinking in terms of ‘fusion’, the creation of a new centre party formed from a merger of Lloyd George’s party and the Conservatives.

The meeting was deliberately held the morning after the Newport by-election which ‘the big beasts’ imagined would demonstrate how crucial the continuation of the coalition was to Conservative Party’s electoral fortunes. Unexpectedly, the Conservative leadership’s calculation completely backfired because the Conservative candidate won easily, pushing the coalition candidate into third place. Few by-elections have had greater repercussions.

Conservative backbenchers were uneasy about the coalition for a multiplicity of reasons.

Unionist-minded MPs took a very dim view of the Anglo-Irish Treaty to which both Birkenhead and Chamberlain were signatories.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEmpire-minded Conservatives were unsettled by plans to confer greater self-government on India and Egypt.

The bellicose reaction of some ministers to Kemal Ataturk’s disregard for the Treaty of Lausanne and the expulsion of the Greek population from Turkey threatened to saddle the country with a fresh and unwelcome military commitment.

Ambitious Conservatives with aspirations to seats in the Cabinet were aggrieved that Conservative strength in the House of Commons was not reflected in the composition of the Cabinet.

Moral issues weighed heavily with Stanley Baldwin. Lloyd George was shamelessly selling peerages to enrich the coffers of his party and himself. Furthermore, Lloyd George was the first Prime Minster since the 3rd Duke of Grafton in the 18th century to live openly with his mistress. Despite his intellectual brilliance as Lord Chancellor, Birkenhead was frequently the worse for drink. Baldwin summed up this sentiment by observing:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad‘England prefers second-class intellects with first-class characters to first-class intellects with second-class characters.’

Thus, there was no shortage of raw material for grievance and dissatisfaction with the coalition. The Newport by election emboldened Conservatives by giving them solid grounds for repudiating the coalition and the outlook of the leadership. ‘The Peasants’ Revolt’ was led Stanley Baldwin, a figure with historic familial ties with Ballinamallard, who told the meeting that Lloyd George was ‘a dynamic force and it is from that very fact our troubles … arise. A dynamic force is a terrible thing. It may crush you but it is not necessarily right’.

Baldwin drove home the message that the ‘Welsh Wizard’ had already split the Liberal Party and it was time to stop him before he replicated that feat with their own Party.

The vote was decisive: 187 Conservative MPs agreed with Stanley Baldwin and only 87 supported Chamberlain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWithout Conservative support Lloyd George appreciated that he could not command a majority in the House of Commons so he resigned within three hours of the Carlton Street vote. Austen Chamberlain also reigned as leader of the Conservative Party.

King George V sent for Law, who had been leader of the Conservative Party between 1911 and 1921, but he declined to form an administration until he had been confirmed as Party leader. On 23 October the Party unanimously endorsed Law’s leadership and he was immediately appointed Prime Minister.

As the Coalitionists in the Conservative Party accounted for most of the brainpower and talent in the party, they imagined that Law would have great difficulty in constructing a new administration, but he did – even if Winston Churchill dismissed it as ‘a Cabinet of the second eleven’. In fairness, Law had the wit to realise this and regarded one of his principal objectives to be to secure the return of ‘the Big Beasts’ to the fold. Law always had an acute appreciation of the importance of party unity.

In the ensuing General Election on 15 November 1922 Conservatives won 345 seats to the Liberals’ 116. Although Labour won an impressive 142 seats, Bonar Law nevertheless had secured a comfortable majority. (These figures are only indicative because party affiliation did not appear on the ballot paper.)