Independent Orange Order founder Robert Lindsay Crawford was dubbed 'a Fenian Protestant'

James Crawford, his father, was a ‘scripture reader’ or evangelist. Matilda Crawford (née Hastings), his mother, hailed from Co Monaghan.

In 1901 Robert was a brewer’s agent and was living with his widowed mother and sister in Arran Quay in Dublin. However, later that year he became the founding editor of the evangelical ‘Irish Protestant’, a position he retained until 1906.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn impressive public speaker, he also proved to be a talented journalist. Until his mid-30s Crawford subscribed to a conventional Protestant and Orange worldview but thereafter his views evolved in new and unexpected directions which would eventually result in his embrace of Irish nationalism and to him being described as ‘a Fenian Protestant’.

The ‘Irish Protestant’ was regarded as ‘a lone voice of protest against the Conservative administration’ in the southern unionist press, an observation highlighting that at the core of Crawford’s political thinking was a deep-seated antipathy to Conservatism and the Conservative Party. Crawford’s other obsession was the growth of ritualism in the Church of Ireland.

In June 1903 Crawford and Thomas Sloan, the independent unionist MP for South Belfast, founded the Independent Orange Order (IOO) with Crawford as grand master and its ideologue.

Crawford insisted that the IOO was ‘strongly Protestant, strongly democratic and strongly Irish’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSloan, an evangelical and an unskilled shipyard worker with a talent for self-promotion, shared Crawford’s hostility to ritualism and the Conservative Party.

Other key figures were Alex Boyd from the Donegall Road and the Rev D D Boyle from Ballymoney, who became grand chaplain of the IOO.

Boyd was a militant trade unionist and the organiser of the Municipal Employees’ Association. He brought a Belfast working-class distrust of the unionist commercial and industrial elite to the order. Boyle, on the other hand, was a Presbyterian minister in Ballymoney, a leading member of North Antrim Land Purchase Association and a strident advocate of the interests of tenant farmers of The Route.

Politically, the IOO appealed to these sectional interests and had serious traction in south Belfast and north Antrim as would be evidenced by the general election of January 1906 in those two constituencies.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1904 in ‘Orangeism, its History and Progress’ Crawford claimed that ‘the unholy alliance between Orangeism and Toryism has been marked by the betrayal of Protestantism, and the promotion on every possible occasion of the power and influence of the Church of Rome’. He also expressed the hope that ‘Orange democracy’ would become ‘a powerful factor in our national life – softening the acerbity of religious and political strife’.

Developing this theme in the Magheramorne Manifesto of July 1905, Crawford was highly critical of all forms of clericalism and urged Protestants and Roman Catholics to unite on the basis of a shared (Irish) nationality. He simultaneously denounced the newly formed Ulster Unionist Council and dismissed unionism as ‘a discredited creed’.

Sloan and the IOO endorsed the manifesto presumably because their political antennae were insufficiently acute to appreciate Crawford’s direction of travel. At this point he was morphing into a liberal rather than unionist.

In May 1906 Crawford was obliged to sell the ‘Irish Protestant’, sales of which were in steep decline because he had comprehensively alienated its readership. In November of that year he contested the North Armagh by-election occasioned by the death of Colonel Saunderson, the Unionist leader. His crushing defeat demonstrated that there was no appetite for his political platform – in North Armagh at any rate.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn January 1907 he became editor of the ‘Ulster Guardian’, the official publication of the Ulster Liberal Association, underscoring the extent of the radical change in his politics.

By 1908 his politics were more than both the ‘Ulster Guardian’ and the IOO could stomach (but for different reasons), resulting in his sacking from the newspaper and his expulsion from the IOO.

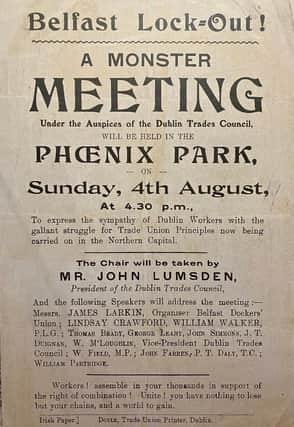

He antagonised the former by his support for the Belfast dock strike (or lock-out), sharing a platform with Jim Larkin, attacking linen barons and his increasing focus on labour issues. Although he denied being a socialist, to Liberal ears he sounded like one.

He antagonised the IOO by extolling the virtues of Dr William Drennan, his admiration for Michael Davitt and his sympathetic but not uncritical interest in cultural nationalism (including the Gaelic League).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile an alliance between the urban working class and tenant farmers might have been politically viable, abandoning unionism and embracing nationalism only served to undermine rather than expand his potential political base. Unlike Bismarck or ‘Rab’ Butler (to whom the axiom is usually credited), Crawford failed to appreciate that ‘politics is the art of the possible’.

In January 1910 Sloan lost his South Belfast parliamentary seat, largely due to ambiguity surrounding his commitment to the Union – partially on account of the content of the Magheramorne Manifesto.

Unable to find employment in Ireland, in June 1910 Crawford emigrated to Canada. He secured a post with the ‘Toronto Globe’ where he was to remain until February 1918 (when they too parted company politically). The quality of his journalism sufficiently impressed his Canadian employers for them to send him in March 1914 to Ireland as a special correspondent to cover what they imagined were the closing stages of the third Home Rule crisis.

In Canada he was proactive in endeavouring to enlist the support of leading Canadian politicians for Irish Home Rule but with limited success. After the 1916 rebellion his politics underwent further change, embracing republicanism. Thus, he supported Sinn Fein, the War of Independence, and the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn recognition of his support for the Irish cause as president of the Protestant Friends of Irish Freedom, an Irish-American lobby organisation, and his political activism both in Canada and the United States, in December 1922 the government of the newly created Irish Free State appointed him as its trade representative in New York.

Crawford died in New York City on June 3 1945.

The Ulster-Scots community periodically produces unconventional people with challenging or idiosyncratic ideas and Crawford is an intriguing example.