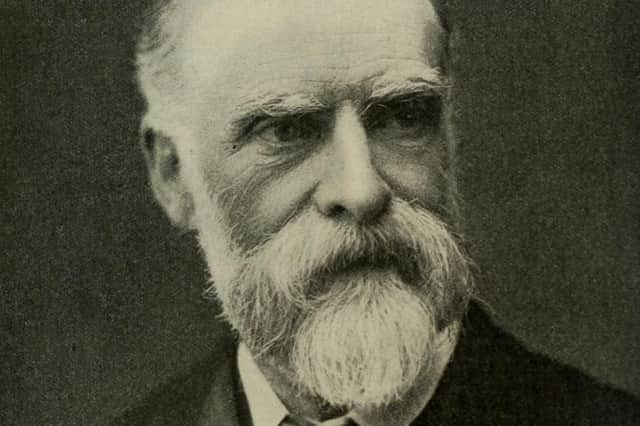

James Bryce, probably the most dazzling and successful Belfast man you’ve never heard of

The term ‘polymath’ might have been devised to describe James Bryce, author, classicist, historian, political scientist, jurist, politician, diplomat, inveterate traveller and mountaineer. (As chief secretary for Ireland, he dragged his officials up Croagh Patrick for exercise in 1906.) British ambassador to Washington, DC, from 1907 to 1913, his magisterial survey of the United States Constitution, ‘The American Commonwealth’, remains a classic. Yet, he is largely forgotten in his native city.

James Bryce was born on May 10 1838 in Arthur Street, Belfast. He was born into a distinguished Ulster-Scots Presbyterian family. Both his father and grandfather merit entries in ‘The Dictionary of National Biography’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEntering the University of Glasgow in 1854, Bryce studied classics and in his second year won a gold medal for Greek and a prize for mathematics. (Glasgow still has a chair of politics named in his honour.)

At Oxford, he was ‘that awful Scotch fellow who outwrote everybody’. He graduated from Trinity College, Oxford, in 1862, and won a scholarship to Oriel. Bryce won many prizes at Oxford. His prize essay on The Holy Roman Empire was published as a book in 1864. Translated into German, French and Italian, the book won him a European reputation in his 20s.

Called to the bar in 1867, he was Regius Professor of Law at Oxford from 1870 until 1893 and co-founded ‘The English Historical Review’ with Lord Acton.

Liberal MP for Tower Hamlets, 1880-1885, and for South Aberdeen, 1885-1907, Bryce held office as under secretary of state for foreign affairs, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and president of the Board of Trade, concluding with a spell as chief secretary for Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the Liberal leader, viewed Bryce as ‘the most accomplished man in the House of Commons’ because ‘he has been everywhere, he has read almost everything, and he knows everybody’.

When Campbell-Bannerman became prime minister in December 1905, he appointed Bryce chief secretary for Ireland rather than foreign secretary, the office to which Bryce aspired and to which he believed himself well equipped to fill.

Home Rule was not a pressing issue for a Liberal government, which after the general election of January 1906, had a massive parliamentary majority, independent of Irish Nationalist MPs. By this stage Bryce considered the Irish unfit for Home Rule and wished Nationalists to settle for something less than full-blown Gladstonian Home Rule. This made him very unpopular with John Redmond and John Dillon, the Nationalist leaders. Although Dillon liked Bryce as a man and admired him as a scholar, he distrusted him as a politician and detested him as an administrator.

In February 1907 Bryce was appointed British ambassador to Washington, DC. F S L Lyons, the biographer of Dillon, observed that Bryce had ‘jumped at the opportunity’ to escape from Irish politicians. Bryce already had made many friends in American political, educational, and literary circles because of his regular visits to the United States since 1870.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis classic work, ‘The American Commonwealth’ (1888), in which he expressed admiration for the American people and their system of government, greatly contributed to his popularity. He calculated that three-quarters of his period as ambassador was directed at resolving differences and improving relations between Canada and the United States. The principal differences were over Alaska, fishing rights and tariffs and in resolving these matters he was extremely successful. He retired as ambassador in April 1913.

During his embassy Bryce visited every state of the American Union. Bryce’s tenure of British embassy in Washington DC overlapped with Whitelaw Reid’s time as United States ambassador to the Court of St James. Therefore, both the United States ambassador to the United Kingdom and the United Kingdom’s ambassador to the United States were Ulster Scots.

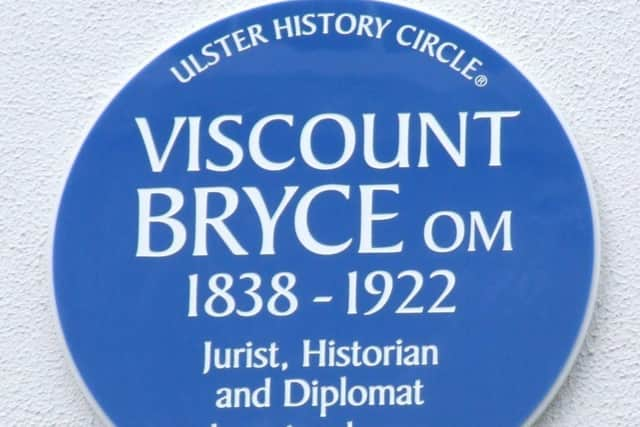

At the beginning of 1914 Bryce was created Viscount Bryce. In the House of Lords he supported the temporary exclusion of Ulster from the terms of the third Home Rule bill. He also became a member of the International Court of Justice at The Hague. Prime minister Asquith commissioned him write a report detailing German atrocities against civilians in Belgium. He was an early advocate for establishing a League of Nations and active American participation in the League. His final speech in the House of Lords was in support of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. Bryce on died January 22 1922 at Sidmouth in Devon.

Although we have not focused on his political career, Bryce’s political achievements might fairly be described as modest. Perhaps he was viewed as ‘too clever by half’ and less able politicians relished frustrating his plans. Such pettiness is not unknown in political life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn contrast, Bryce’s achievements outside politics, especially in scholarship and diplomacy, were and remain impressive. ‘The American Commonwealth’ is still a highly regarded book. Like Walter Bagehot’s ‘The English Constitution’ it is a brilliant analysis of the working of the politics of that great country at a precise moment in its history. Woodrow Wilson reviewed it favourably in ‘Political Science Quarterly’. ‘The English Historical Review’ that he and Lord Acton founded in 1886 is still being published and is one of the most prestigious academic journals in the world.

As a diplomat, Bryce was a conspicuous success in the United States. During the Great War, the German a mbassador to the United States was greatly relieved that he did not have to contend with Bryce as his opposite number. Although the United States was neutral until 1917, the British probably received a better hearing in the United States than might have been the case largely because of Bryce’s legacy.

Turning briefly to politics, is it possible that if Bryce had been more successful in persuading Gladstone of the reality of ‘the Ulster Question’ in 1885/86 or 1892/93, the history of this island in the 20th century might make for more pleasant reading? Gladstone was genuinely ignorant and extremely ill-informed about the realities of Ulster life. Bryce’s failure to educate the Liberal political elite in these matters might be regarded as a matter of serious regret.