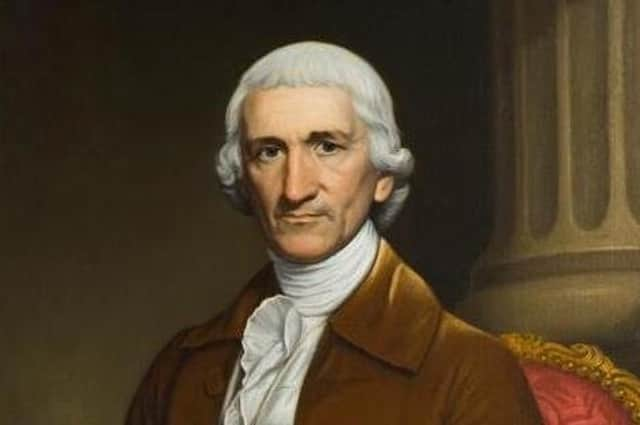

Maghera-born Charles Thomson: A leading light of the movement that became the American Revolution

Charles Thomson was born in Gorteade, near Maghera, Co Londonderry, in 1729. After the death of his mother in 1739, John Thomson, his father, an Ulster-Scots Presbyterian linen bleacher, emigrated to the British colonies in America with Charles and his two or three brothers.

Unfortunately, John Thomson died at sea, and the boys arrived in America as penniless orphans, robbed of all they possessed by the ship’s captain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA kindly blacksmith in New Castle, Delaware, took Charles under his wing. He had the good fortune to be educated in New London by Francis Alison, another Ulster-Scot. In 1750 he became a Latin tutor in Philadelphia and by the end of the decade had developed an absorbing interest in politics.

Unfortunately, we know comparatively very little about this clearly significant period of Thomson’s life because he destroyed all his papers and correspondence between the late 1750s and the 1770s. However, we do have the testimony of John Adams, the second President of the United States, that in Pennsylvania politics Thomson played a role comparable to that of Samuel Adams in Massachusetts. In other words, he was one of the leading lights of the movement that became the American Revolution and was one of the principal architects of the American republic and its political culture.

In 1774 he became Secretary to the Continental Congress and got married for the second time within a week. His bride was Hannah Harrison, a sister of a future signatory of the Declaration of Independence and a relation of John Dickinson, the so-called ‘Penman of the Revolution’, who probably acted as matchmaker.

Thomson remained Secretary to the Continental Congress until 1789. Through those 15 years, 343 men served as delegates to the Continental Congress, many of whom came and went but Thomson’s presence as Secretary provided continuity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Continental Congress was a fractious body. For example, in August 1779 John Fell, a delegate from New Jersey, recorded that the day was ‘marked by a disagreeable complaint of Mr Lawrence [actually Henry Laurens] against Secretary Thompson[sic]’. Biographer Boyd Stanley Schlenther described the incident as ‘a piece of congressional farce’ in which ‘the two men physically wrestled with a copy of the printed “Journal” in front of the whole Congress‘. In January 1780 James Searle, a close ally of John Adams, engaged in a cane fight with Thomson after alleging that Thomson had misquoted the minutes. Samuel Holten, a member of Congress recorded: ‘Yesterday Mr Searle cained [sic] the s[ecretar]y of Congress, & the s[ecretar]y of Congress returned the same salute.’

His role as secretary to Congress was by no means limited to clerical duties. Thomson’s thinking was allegedly very close to that of George Washington. According to Schlenther, Thomson ‘took a direct role in the conduct of foreign affairs’. Fred S. Rolater has even suggested that Charles Thomson was essentially the ‘Prime Minister of the United States’.

The American Declaration of Independence is written in Thomson’s hand. Although he did not sign the original document, his name (as secretary) appeared on the first published version of the Declaration.

In 1782 Thomson designed the first Great Seal of America and chose what was widely considered the de facto motto of the United States: ‘E pluribus unum’ (One out of many), an expression of Thomson’s fervent belief in the importance of the unity of the States.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThomson’s last official duty was to convey Congress’s invitation to George Washington at his Mount Vernon home in Virginia to become first President of the United States.

Thomson resigned as secretary of Congress in July 1789 and handed over the Great Seal, bringing an end to the Continental Congress.

An active Presbyterian, church elder and scholar of Greek, he produced the first English translation of the New Testament published in America and the first translation of the Septuagint into the English language (The Septuagint is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament made in the third century BC.)

In retirement, Thomson also pursued his interests in scientific research relating to agriculture and beekeeping.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough Thomson had his critics and detractors who prevented him securing employment in the service of the newly established United States after 1789, his widespread reputation for integrity gave rise to a proverb: ‘It’s as true as if Charles Thomson’s name were to it.’

There was no one better placed to write a history of the American Revolution than Thomson. He completed such a history but then unfortunately, to the chagrin of historians ever since, decided against publication and destroyed even his notes. Historians contrive to impose a greater coherence on the past than was obvious to those who lived through events, a point fully appreciated by Thomson in his explanation of why he declined publish his eyewitness account of the activities of ‘the Founding Fathers’:

‘I ought not, for I should contradict all the histories of the great events of the revolution, and show by my account of men, motives and measures, that we are wholly indebted to the agency of Providence for its successful issue. Let the world admire the supposed wisdom and valor of our great men. Perhaps they may adopt the qualities that have been ascribed to them, and thus good may be done. I shall not undeceive future generations.’

Charles Thomson died on 16 August 1824 at the age of 94, outliving all but three of the signatories of the Declaration, the exceptions being Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Charles Carroll.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn his memoirs Dr Benjamin Rush described Thomson as ‘a man of great learning and general knowledge, at all times a genuine republican’. Thomson also earned the admiration of Washington and Jefferson and in time even John Adams (who had not always been an admirer).

Although Thomson occupied a place at the very heart of the Revolution as the one and only Secretary of the Continental Congress, Thomson’s profile in American history is not great as it really ought to be because he chose to destroy the bulk of his papers relating to the Revolution and he played no part in politics for the last third of his life.