Malachi O’Doherty book extract: British-Irish relations hit a low in late 1971 over security at the Northern Ireland land border

Ten days after that big Chequers summit in September 1971, Edward Heath wrote to Jack Lynch to update him on progress.

He informed the Taoiseach, the prime minister of a neighbouring state, that he was about to bomb their shared border.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

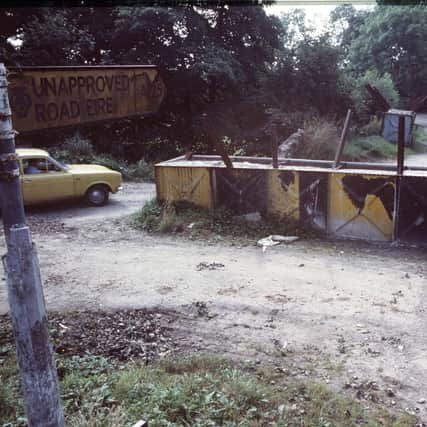

Hide AdHis message read: ‘Our intention is, as a first step, to block 84 of the so-called “unapproved” crossings.’

This plan seemed to the Irish to be more a political insult than a practical security measure, an appeasement of hardline unionists who wanted the Republic punished for what they saw as dilatory measures against the IRA.

The letter continued, ‘This will in most cases be achieved by cratering the roads, but care will be taken wherever possible to avoid unreasonable inconvenience, for example to farmers whose land lies on or athwart the Border. The second stage will be to “hump” the “approved” crossing places, so as to slow traffic down and facilitate stopping and searching.’

British army units had been crossing the border on occasions and the Irish were annoyed about that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdQuestions in the Dáil, the Irish parliament, on November 3 1971 revealed that the Irish were aware of 40 such crossings by armed soldiers, all of them illegal infringements on the sovereign territory of a supposedly friendly neighbour.

Soldiers had also been flown over Irish territory on seventeen occasions.

The British ambassador John Peck then wrote to Jack Lynch on November 5 to assure him that his government had thoroughly investigated claims ‘that British armed forces have crossed the border into the Republic’.

He wrote, ‘I expect you would prefer it if I did not burden you personally with them [the results of the investigation] at this stage.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo he was sending them to the Department of Foreign Affairs.

‘I am therefore writing to assure you most emphatically that British Army units are not crossing the border deliberately, that all units operating in the border area have strict instructions to this effect, and these instructions have been made even more explicit.’

The army had also bombed bridges on the border to inhibit the IRA moving back and forth between the two jurisdictions, smuggling arms or launching attacks and then retreating into territory on which the army could not lawfully pursue them.

Ambassador Peck assured the Taoiseach that ‘[w]here explosions near the border are deemed necessary, they are to be carried out so that no debris falls upon the territory of the Republic’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPeck added a message from the prime minister which reads like an elegant brush-off.

At their last meeting at Chequers, Heath and Lynch had agreed that they would meet again in the autumn, with dates yet to be confirmed.

‘Mr Heath has asked me to say how welcome you will be at any time; but he fully understands that your many preoccupations could make it hard for you to leave Dublin at present, and he does not want to add to your difficulties by proposing a definite date at this stage.’

So, gently phrased, the point was that there would be no return invitation to Chequers and if Lynch wanted another meeting he would have to ask for it himself.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis reads to me as if the British were punishing Lynch for annoying them with a concern that they probably thought he should have been more flexible about.

If Lynch was going to preoccupy himself with trivialities like soldiers stepping over the border while engaged in a war on the IRA, then Heath was going to leave him free to busy himself with the matter and get on with more serious concerns himself.

But a sovereign country is entitled to ask a foreign army to stay out of its territory without being sneered at.

One of the Irish complaints about border intrusions had followed an incident in which a man had been killed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA Department of Foreign Affairs note on the incursions reads: ‘On 29th August, 1971 a border incursion resulted in a fatal shooting within the Six Counties [the official Irish term for Northern Ireland] after a British army patrol had recrossed the border into the North. A strong complaint was conveyed to the British authorities on that occasion about their failure to control movements of their troops in border areas which could be prejudicial to the peace.’

One can be a bit more indulgent of the sniffy tone of the British ambassador’s letter and Heath’s reduced enthusiasm for another meeting with Lynch when it is clear that the fatality referred to in the note was of a British soldier, Ian Armstrong.

Armstrong and others had crossed the border at Crossmaglen in County Armagh. After going a hundred yards into Irish territory they turned around and found their way blocked by protesters.

There was a tense standoff for two hours, the army unable to use force to break through the protesters and the protesters knowing that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis gave the IRA time to organise an ambush in the North when the soldiers eventually returned. The protesters set fire to one of the army vehicles.

When the soldiers eventually got back into the North their troubles weren’t over. One of the vehicles suffered a puncture, compelling them to stop.

The soldiers got out to fix the puncture and exposed themselves to IRA snipers in the hills around them. Those snipers killed Armstrong and wounded another soldier.

So the army had a very good reason not to encroach on Irish territory. Having moved beyond the area in which they could legally operate, their weapons were useless to them and any Irish civilians might presume the right to detain them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe most recent incident had occurred when British soldiers faced protesters after bombing a crater in a cross-border road at Castleblaney in County Louth. The Irish complaint said: ‘British forces were observed in a firing position inside the 26-Counties.’

An armed Irish army soldier might have felt compelled to shoot a British soldier who appeared to be preparing to fire at an Irish civilian.

Serious indeed.

Confusion about the precise location of the border made life dangerous for the Irish police too.

A year later, Garda Samuel Donegan, 61, triggered a roadside booby trap near Newtownbutler, just a few yards inside Northern Ireland, and lost his life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere was a dangerous vulnerability in relations between the two countries with the potential to turn the Troubles into an armed conflict between Britain and Ireland, and this on the eve of both of them entering the European Community.

The IRA would have loved that to happen.

Years later a member of the Official IRA told me that his organisation had discussed plans to trigger such a crisis. Volunteers would join the Irish army then take armoured vehicles and drive them into Derry.

It never happened.

Ireland never had the capability to take on the British army, let alone the desire, but even a brief exchange of fire costing Irish lives would have resonated around the world as validation of the IRA campaign for British withdrawal.

The British believed that the Irish government was soft on the IRA and British ambassador John Peck came back at the Taoiseach with an angry letter after further murders close to the border.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKenneth Smyth was 28 years old and a part-time soldier in the Ulster Defence Regiment. He was off duty. His catholic friend Daniel McCormack had also been in the regiment but had left. Smyth had recently got married. McCormick was 29 years old and had five children and lived in Strabane.

They were planning to do a day’s work together, sitting in a civilian Land Rover waiting for another workmate to join them. It was nine o’clock in the morning, a couple of weeks before Christmas, near the village of Clady, right on the border.

It is a beautiful area, more verdant than the rugged north of County Donegal, but still you could feel when you crossed the border there that you had entered into a more placid agricultural region.

The predominant smell in the air at that time of year would have been turf smoke from domestic fires.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStrabane on the northern, British side had a strong IRA presence. Nearby in the Republic, Castlefin was also a base for activists and they were out to prove that day that they had free access to the border and could cross it as they pleased.

A casual assassin shot Kenneth Smyth and David McCormack dead. Ambassador Peck’s letter says the killer was joined by another man, and ‘then walked across the Border about 200 metres away’.

This was the second attempt to kill Kenneth Smyth, who had only been married for three months. In August 1971, while he lived with his parents, gunmen called at the house looking for him when he was out.

The British were livid about the ease with which the killers had been able to walk to safety, out of the reach of the army.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen two days later, in the same area, about 400 metres from the border, members of the Official IRA shot and killed Senator Jack Barnhill.

They said afterwards that they had not set out to kill him. They had only wanted to burn down his house but the man had had the temerity to try to obstruct them.

The account in Lost Lives says that Jack Barnhill answered the door to his killers and they shot him and laid his body beside their bomb, telling his wife she had two minutes to get out of the house.

The ambassador said, ‘HMG regard it as intolerable that the Republic should provide a refuge from which the murderers can operate with impunity, whether the men are from the south or the north.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd he set out details of the action that the British wanted the Taoiseach to take, which was to instruct the army and the Irish police, the Garda Síochána, to ‘take more vigorous action against the gangs operating across the Border, particularly near Strabane’.

The hope was that ‘this could provide the basis for close cooperation between security forces on both sides of the Border and for follow-up action should the RUC or Gardai obtain leads to perpetrators of these crimes’.

Perhaps he was hoping that ‘follow-up action’ would entail the right for forces on either side of the border to cross it in pursuit of suspects. That would never be agreed to.

Peck also demanded more effective extradition procedures. Lynch had already said he preferred to see suspects tried rather than interned.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPeck said he found it hard to accept ‘that those against whom charges have been brought, and will be brought to trial if caught, can enjoy a safe haven from which they can perpetrate further crimes’.

This was a low point in British–Irish relations with the British effectively accusing the Irish government of making life easy for the IRA.

The Irish, however, rejected the claim that they were soft on terrorism and denied that the ease with which gunmen could cross the border was part of the problem.

Even so, the Taoiseach Jack Lynch commended that the two governments should jointly ask the United Nations Security Council to provide an observer group on both sides of the border ‘to expose or prevent activities prejudicial to the peace’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was in a speech in the Dáil on 16 December, just four days after the killing of Senator Barnhill. He claimed that the whole question of border security was being raised to shift attention away from a failure of British policy: ‘Every objective observer is well aware that the causes of violence in the North lie in the refusal of civil and human rights to 40 per cent of the population in the area for half a century – a deprivation which current policies are not correcting.’

The blame, as he saw it, lay with the unionist government in Stormont.

• The year of Chaos: Northern Ireland on the brink of Civil War, 1971-72 by Malachi O’Doherty (Atlantic Books)

——— ———

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers — and consequently the revenue we receive — we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Subscribe to newsletter.co.uk and enjoy unlimited access to the best Northern Ireland and UK news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.newsletter.co.uk/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Ben Lowry

Acting Editor