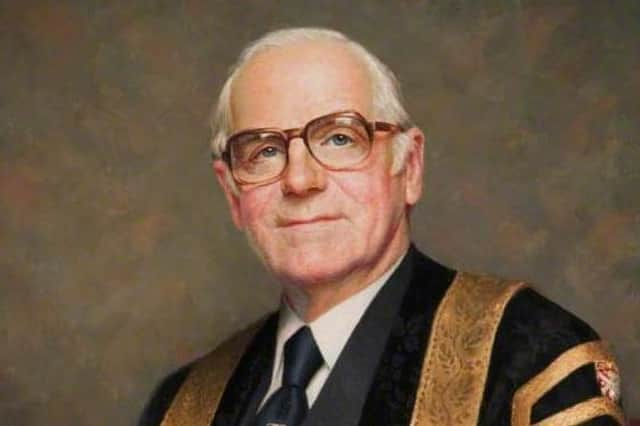

Sir Samuel Curran, the Ballymena-born physicist who was part of Manhattan Project that developed the atom bomb

Samuel studied mathematics and physics at Glasgow University before earning his PhD from Cambridge.

At Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory Ernest Rutherford (‘the father of nuclear physics’ under whose direction John Cockcroft and the Methody-educated Ernest Walton split the atom) was his head of department and he worked closely with C T R Wilson, who won the Nobel prize for physics in 1927 and inventor of the cloud chamber (which was widely used in the study of radioactivity, X rays and other nuclear phenomena).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the Second World War, he joined the Royal Aircraft Establishment along with his wife, fellow physicist Joan Curran (née Strothers), to work on the development of radar and the proximity fuse.

The Currans’ radar equipment would also be used by all Bomber Command aircraft and Coastal Command.

The proximity fuse would prove crucial in the destruction of over 90% of the German V-1 rockets.

Joan Curran was credited with having ‘the scientific equivalent of gardening green fingers’. One of her innovations was the scattering of strips of tin foil in the air disrupting enemy radar. In June 1944 the RAF dropped huge quantities of tin foil over the English Channel simulating an invasion force of ships heading towards the Pas de Calais, helping to convince the Germans to concentrate forces there rather in Normandy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1944, Samuel Curran went to work on the Manhattan Project (the codename for the US-led development of the atomic bomb) at the Radiation Laboratory in Berkley, California, where his specialism was the separation of isotopes of uranium.

In his spare time, he invented the scintillation counter, a device which is still used in laboratories around the world for measuring radioactive activity.

Reflecting on his role in the creation of the atomic bomb, Curran admitted to Tam Dalyell, the long-serving Scottish Labour MP, that he did not ‘agonise’ as much as some of his colleagues (and here he probably had Sir James Chadwick, who also worked on the separation of isotopes of uranium, in mind) but he did wonder about ‘where the ultimate results would lead’.

In the early 1990s, Curran told Sir Tom Devine, Scotland’s pre-eminent historian, that the Allies were in the dark about how far advanced the Nazis were in developing their own bomb but it was vital that the Allies built their bomb before the Nazis did.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCurran deplored the horrendous loss of life at Hiroshima and Nagasaki but maintained the dropping of the bombs was essential to bring the war in the Far East to a close.

After the war, Curran returned to the UK to work at the University of Glasgow despite being offered a post at the University of California.

Between 1955 and 1958 he worked on the development of the British hydrogen bomb at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment, the main centre for nuclear power research in the UK, and then became chief scientist of the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston for a year.

In 1959 Curran became the principal of the Royal College of Science and Technology, a prestigious institution which produced many of the great engineers and scientists of the 19th and first half of the 20th century. He steered the institution through to full university status as the University of Strathclyde in 1964.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCurran was appointed the university’s first principal and vice-chancellor.

Strathclyde was the first new university in Scotland for almost 400 years and the first technological university in the UK.

Curran was passionate about the importance of technology.

He blamed much of the industrial and manufacturing decay of the UK on the failure of government and the universities to appreciate the importance of technological education. He stressed the importance of co-operation with industry and was a pioneer in the appointment of top industrialists as visiting professors.

At the Labour Party Conference of 1963 Harold Wilson, the new party leader, spoke of his party’s plans to harness a ‘scientific revolution’ to modernise British industry and drive economic progress: ‘the Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods on either side of industry’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe influence of Sam Curran may be readily discerned in this.

As prime minister, Wilson told Tam Dalyell: ‘Sam is one of the people in higher education whose good opinion of our policy I really covet.’ Dalyell seems to have acted as a conduit between Curran and Wilson.

Curran served on a wide range of governmental bodies relating to science and technology.

He was responsible for the creation of Engineering Laboratory in East Kilbride whose facilities were available to all the Scottish universities. Access was later extended to QUB, a development perhaps attributable to his Ulster birth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs honorary president of the Scottish Polish Cultural Association, he forged an extremely successful working relationship between Strathclyde and the technical University of Łódź. This was even more remarkable because it was achieved during the Cold War when Poland was still part of the Soviet bloc.

Following the birth of their handicapped daughter, the Currans established the Scottish Society for the Parents of Mentally Handicapped Children (now known as Enable Scotland). He served as its president from 1964 to 1991.

According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, two things particularly irked Curran: the very low salaries paid to scientists by comparison with businessmen and the state’s failure to recognise how science and technology had contributed to WWII.

Sir Samuel Curran died on February 15 1998. Tom Devine described him as ‘a man of gravitas and intellect’ but without ‘pomposity or side’. Tam Dalyell regarded him as ‘one of the great Scots of the 20th century – in the tradition of the heroes of the 18th-century Scottish Enlightenment’. No one would seriously quibble with either assessment.