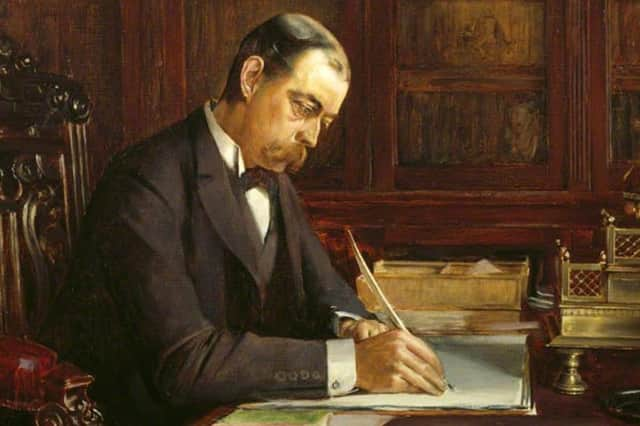

Why Lord Randolph Churchill agreed to play the ‘Orange card’ in famous Ulster Hall speech of 1886

However, these significant Ulster-Scots family relationships played no significant part in accounting for Churchill’s famous speech in the Ulster Hall on February 22 1886.

Although fluent and articulate, Lord Randolph was a political opportunist rather than a conviction politician. Prior to the revelation of Gladstone’s conversion to Home Rule in December 1885, Churchill’s conduct overall evidenced admiration for C S Parnell and far greater sympathy for Nationalism than Unionism, so much so that the Rev Dr R R Kane, Orange County Grand Master of Belfast, suspected that Churchill had a secret commitment to Nationalism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHence Kane’s declaration that if Churchill, after the manifest failure of the Conservative Party nationally to look after the electoral interests of Ulster Conservatives between 1884 and 1885, ever set foot in Ulster ‘things would be made very hot for him’.

As recently as November 1885 Churchill had disparagingly referred to ‘those foul Ulster Tories who have always been the ruination of our party’. Even between December 1885 and February 1886 Churchill’s unionism was so irresolute that he was flashing orange and green like a defective traffic light.

Then how do we account for his unequivocal declaration in favour of Ulster and the Union in February 1886?

Actually, Churchill, who was born 175 years ago on February 13 1849, was subject to far more extensive and continuous unionist influence behind the scenes than was appreciated at the time, and the credit must disproportionately go to Gerald Fitzgibbon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFitzgibbon was the most brilliant of a brilliant generation of political and legal minds produced by Trinity College, Dublin, which included Michael Morris, David Plunket and Edward Gibson.

All four were Tories and committed unionists. (Admittedly Morris, a Roman Catholic unionist from Galway, was very briefly a Liberal.) Plunket and Gibson both served as MPs for Trinity. Gibson even became Lord Chancellor of Ireland. Although Fitzgibbon never became an MP or Lord Chancellor, he was the dominant figure in Irish legal circles, both as a barrister and a judge, for more than a generation.

In the late 1870s Fitzgibbon had befriended Churchill who was then acting as private secretary to his father, the 7th Duke of Marlborough, who was the lord lieutenant of Ireland from 1876 to 1880.

Fitzgibbon became Churchill's Irish political mentor, and for the rest of his life Churchill regularly attended Fitzgibbon's celebrated Howth Christmas parties which might be regarded as ‘the haute école of intelligent Toryism’ – even more so than TCD.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was Fitzgibbon who between December 28 and 31 1885 persuaded Churchill to play the ‘Orange card’ in 1886. Although Fitzgibbon viewed popular Ulster Protestantism with some distaste because it constituted an obstacle to some of his plans for winning Roman Catholic support for Conservatism, he constantly reminded Churchill that, in a crisis, Ulster Protestants were the only reliable popular element of Irish society which would never willingly sever the Union. His mother’s family background – Ellen Patterson was the daughter of an Ulster-Scots Belfast merchant family – gave him a heightened appreciation of this.

Considering Churchill’s public conduct, rancour existed between Churchill and Edward Saunderson, the MP for North Armagh and the rapidly emerging leader of Irish Unionism.

Saunderson did not trust Churchill and in this he was not mistaken. Churchill was perfectly capable of playing both sides of the street and that was exactly what he was intending to do by intriguing with the Roman Catholic archbishop of Dublin. (The 15th Earl of Derby’s assessment of Churchill has merit: ‘thoroughly untrustworthy: scarcely a gentleman and probably more or less mad.’)

Nevertheless, in January 1886 Hugh Holmes, the Dungannon-born Irish attorney-general, introduced Churchill to Saunderson and succeeded in achieving a rapprochement.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn January 27 Churchill placed himself at Saunderson’s disposal for a meeting in Belfast whenever Saunderson thought necessary. Therein lies the immediate origins of the Ulster Hall speech, the meeting in the Ulster Hall being the climax to a series of province-wide public meetings, organised by the Orange Order and Ulster Conservatives, expressing opposition to Home Rule.

Contrary to the received wisdom, Churchill’s Ulster Hall speech came close to being a model of restraint and responsibility, especially when compared to a bellicose speech he gave to his Paddington constituents on February 13 – his 37th birthday. Furthermore, Churchill did not say ‘Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right’. His message in the Ulster Hall was essentially that Ulster need not fight but should leave matters to the politicians. The oft-quoted slogan was first deployed in an open letter to a Glasgow Liberal Unionist on May 9 1886.

Churchill did not attach too much significance to his brief excursion to Belfast. Certainly, he had no plans to maintain contact with ‘those abominable Ulster Tories’.

Churchill’s nationalist friends, apart from Thomas Sexton, the MP for West Belfast, were not especially upset. They dismissed Churchill’s antics simply as Churchill being Churchill.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUntil comparatively recently, subsequent generations of nationalists have taken a different view. Believing unionists to be incapable of independent thought and autonomous action, they naively credited Churchill with creating an ‘Ulster Question’ which would not have otherwise existed. The reality is that Ulster unionists had perfectly good and cogent political, economic and religious reasons to resist Home Rule. They most emphatically did not require Churchill’s encouragement to do so.

Churchill (or perhaps more accurately Fitzgibbon) was correct in discerning that Ulster was a cause which could mobilise opinion against Gladstone and Liberalism. The ‘Orange card’ did prove stunningly successful electorally: the Conservatives (and their Liberal Unionist allies) enjoyed office for 17 out of the next 20 years, almost entirely due to the Home Rule issue.

For Ulster unionists, Churchill’s Ulster Hall speech inaugurated a relationship with the Conservative Party which lasted almost a century until it was finally sundered by Margaret Thatcher at Hillsborough with the signing of Anglo-Irish Agreement on November 15 1985.