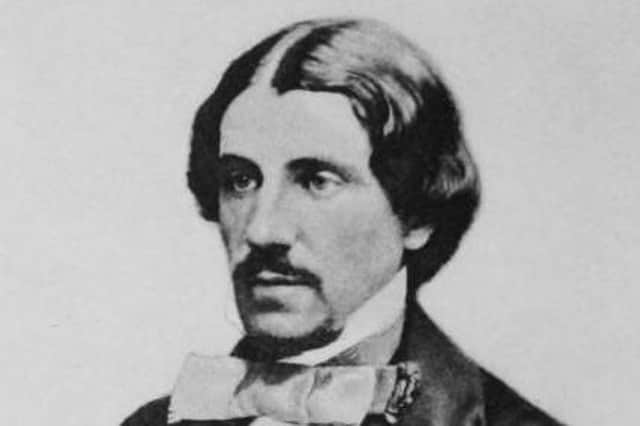

William Allingham, son of Ballyshannon, was a friend of many 19th century literary giants

Thus, he merits inclusion in ‘The Oxford Companion to English Literature’. It is also claimed that he was a significant influence on W B Yeats and John Hewitt.

Allingham was born on March 19 1824 in Ballyshannon, Co Donegal, eldest of five children of William Allingham, a merchant and bank manager, and Elizabeth Allingham (née Crawford).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis Ulster-Scots mother died when Allingham was nine. He was educated locally and then boarded at Killeshandra. He left at 14 to work in the Provincial Bank in Ballyshannon. Subsequently he served in its branches in Armagh, Strabane and Enniskillen.

Seven years later he became principal customs officer for Co Donegal at £80 a year, making returns on cargoes, emigrant ships, and wrecks.

A budding poet, he published poetry and in 1843 began corresponding with the prolific and influential poet, essayist and journalist Leigh Hunt.

By 1847 he was paying annual visits to London and through Hunt was introduced to many leading literary and cultural figures of the day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis friends included Nathaniel Hawthorne, Robert and Elizabeth Browning, Coventry Patmore, W M Thackeray, Francis Sylvester Mahony, and Edward and Georgina Burne-Jones, but his most important friendships were with Alfred Tennyson, D G Rossetti, and Thomas Carlyle.

As he corresponded with these people and recorded his encounters with them in his letters and diaries, these have value in our understanding of Victorian literary culture.

In 1850 he published a volume entitled ‘Poems’ which included ‘The Fairies’ which he had penned in Killybegs in 1849.

Up the airy mountain, Down the rushy glen,

We daren’t go a-hunting for fear of little men;

Wee folk, good folk, Trooping all together;

Green jacket, red cap, And white owl’s feather!

Down along the rocky shore some make their home,

They live on crispy pancakes of yellow tide-foam;

Some in the reeds of the black mountain-lake,

With frogs for their watchdogs, All night awake.

High on the hill-top the old King sits;

He is now so old and grey He’s nigh lost his wits.With a bridge of white mist Columbkill he crosses,

On his stately journeys From Slieveleague to Rosses;

Or going up with music on cold starry nights,

To sup with the Queen of the gay Northern Lights.

They stole little Bridget for seven years long;

When she came down again her friends were all gone.

They took her lightly back, Between the night and morrow,

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey thought that she was fast asleep, But she was dead with sorrow.

They have kept her ever since deep within the lake,

On a bed of flag-leaves, Watching till she wake.

By the craggy hillside, Through the mosses bare,

They have planted thorn trees for pleasure, here and there.

Is any man so daring as dig them up in spite,

He shall find their sharpest thorns in his bed at night.

Up the airy mountain, Down the rushy glen,

We daren’t go a-hunting for fear of little men;

Wee folk, good folk, Trooping all together;

Green jacket, red cap, And white owl’s feather!

Those who recall the poem from childhood may be struck by how much darker it is than the whimsical poem lodged in their hazy memory. These fairies were not benign but capricious and menacing beings.

Many 19th-century people still believed in fairies and newspapers carried reports of fairy sightings, curses and abductions (such as that of ‘little Bridget’). As late as 1895 Bridget Cleary, a real-life Bridget from Co Tipperary, was killed by her husband, family, and neighbours because they thought she was a fairy changeling.

Having found journalism in London in the early 1850s disagreeable, he returned to work in the customs in Coleraine and at Ballyshannon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, to maintain his contacts with the literary scene in London, he transferred to Lymington on the south coast of England – adjacent to the New Forest.

‘Laurence Bloomfield in Ireland’, his most ambitious work, dealing with the Irish land question, appeared in 1864.

Admired by Gladstone and Turgenev, Gladstone even quoted it in the House of Commons and Turgenev claimed that it transformed his understanding of the Irish question.

‘The Eviction’ was inspired by ‘Black Jack’ Adair’s eviction of 44 families, making 244 people homeless, including 159 children, from his Derryveagh estate in order to clear 11,600 acres to make way for sheep and deer in 1861.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAdair, an Ulster-Scot, may have been motivated by his aesthetic appreciation for the beauty of the landscape rather than economic considerations. He claimed that he had purchased the property because he had been ‘enchanted by the surpassing beauty of the scenery’. This may even be true but the tenantry presumably spoiled the view.

As the historian W E Vaughan points out, John George Adair was an atypical landlord. Although the 3rd Earl of Leitrim, another Donegal landlord, was allegedly ‘notorious’ (and certainly obnoxious) and was murdered in April 1878, both the 2nd and 4th Earls of Leitrim were conspicuously good landlords.

John Hamilton of St Ernan’s, an estate between Ballyshannon and Donegal town, was a landlord celebrated for his ‘conscientious benevolence’. The parish priest praised him for going around doing good ‘like his Master’.

In August 1874 Allingham married Helen, daughter of Alexander Peterson, a doctor and a member of an extremely well-connected Derbyshire Unitarian family. On her mother’s side she was related to Joseph Priestly and Mrs Gaskell. She was 24 years younger than he was and an accomplished watercolourist and illustrator.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAllingham always viewed Ballyshannon with affection, recording in his diary: ‘The little old town where I was born has a voice of its own, low, solemn, persistent, humming through the air day and night, summer and winter.’

He took great pleasure in hearing his poems sung as ballads in its streets. Although he died in Hampstead in November 1889, his ashes were interred in the grounds of St Anne’s Parish Church in Ballyshannon.