Collapse of Stormont 1972: Unionism rallied when Westminster said ‘direct rule’

and live on Freeview channel 276

With the level of terrorist violence in Northern Ireland in early 1972 spiralling towards an all-out civil war, the UK Government took the unprecedented step of collapsing Stormont and introducing ‘direct rule’ from Westminster.

The Cabinet of NI Prime Minister Brian Faulkner, unionist political representatives and the wider unionist community, having stood firm against the terrorist onslaught, were left reeling at this shock “betrayal” by Downing Street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn March 24, 1972, UK Prime Minister Edward Heath announced that a one-year suspension would be imposed on the government of Northern Ireland with all security decisions taken in London.

Unionists refused to serve on a newly formed Advisory Commission under the control of new Northern Ireland Secretary William Whitelaw, and Mr Faulkner said that his Cabinet would resign when the direct rule emergency legislation had passed thought the UK Parliament by the following week.

As direct rule was announced in the House of Commons, Brian Faulkner read a statement outside Hillsborough Castle.

He said: “This is a serious and sad situation, reached after three years of the most strenuous efforts to reform our society on a basis at once thought fair and realistic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I thought by our actions and our attitude we had earned the right to the confidence and the support of the United Kingdom Government.”

Mr Faulkner also expressed fears that the terrorist violence would continue to escalate.

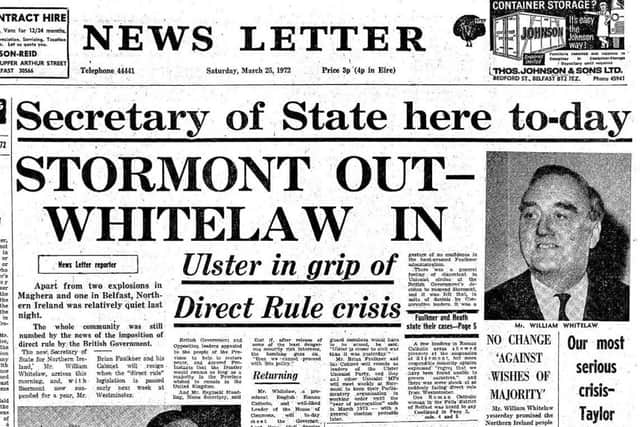

The day after the direct rule announcement, the News Letter’s headline said: “Stormont out - Whitelaw in,” and “Ulster in grip of a of Direct Rule crisis.”

The paper’s editorial reflected the anger being felt among all shades of unionism. This was the first time Stormont had been collapsed since the formation of the state in 1921.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Betrayal is a bitter, dangerous word that is not used carelessly except in anger,” the Morning View column stated.

It went on to say: “No assurances that Edward Heath may give, or has given, as to the duration of the suspension of Stormont, or any other dealing with the future of the Province, will remove that word from the minds of at least one million British citizens”.

In its main front page report on March 25, the News Letter described a collective state of shock affecting the unionist community, however, the “numbness” it reported was soon replaced by palpable anger and calls of mass protests.

Ulster Vanguard Movement leader William Craig (pictured above) urged workers to down tools for two days on Monday, March 27 and Tuesday 28, declaring that a situation was developing that could led to Vanguard members having to arm themselves in defence of Protestant areas.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe is quoted as saying: “Ulster is closer to civil war than it was yesterday.”

On the streets terrorist violence continued to escalate, with an upsurge in support for loyalist paramilitary organisations.

Although both the Provisional and Official IRA wanted the Stormont institutions dismantled, they also rejected the idea of any new arrangements short of a full British withdrawal.

In a statement following what had been described as “crisis talks” between Edward Heath and Brian Faulkner on March 22, PIRA chief of staff Sean MacStiofian issued a statement saying that no matter what initiative the British Government adopted, the campaign of violence against Northern Ireland would continue.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Central Citizens Defence Committee, described by the News Letter as “representing moderate Roman Catholic opinion,” in west and north Belfast welcomed direct rule. The Vatican also issued a statement saying it hoped the initiative would “contribute to a peaceful solution to the problem”.

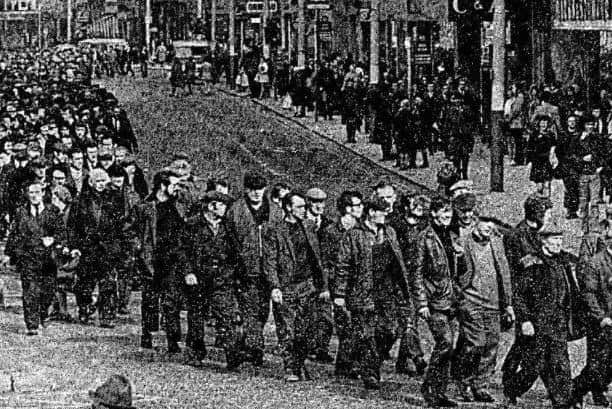

But the daily cycle of bombings and shootings continued and the first of the mass unionist protests began when 10,000 workers marched from Harland & Wolff to Belfast City Hall and back to the shipyard.

Tens of thousands of protesters then gathered at Stormont on March 28 as the NI Parliament sat for the last time before direct rule was ratified by Westminster (main picture).

As the Northern Ireland (Temporary Provisions) Act 1972 was being rushed through the UK Parliament, several unionist MPs launched scathing attacks on the government’s decision. South Belfast MP Rafton Pounder said there was almost universal feeling among unionists that they had been “betrayed, sold out and gravely let down”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn one of his last acts as NI premier, Brian Faulkner signed into legislation new laws prohibiting the leaving of unattended vehicles in many town and city centres.

That bill was a direct response to the first major car bomb of the Troubles – a 100lb device that exploded opposite the News Letter’s offices in Belfast’s Donegall Street claiming seven lives on March 20.

Although initially designed as a temporary measure, Stormont remained closed for much of the following three decades.

The NI Assembly Act of May 1973 allowed for the restoration of a devolved government and, following the Sunningdale Agreement, a powersharing executive was established in January 1974.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was a fierce unionist backlash against those powersharing arrangements and an anti-Sunningdale coalition secured a majority of votes in 11 of the 12 constituencies. The Ulster Workers Council general strike soon followed, leading to another collapse of the executive.

Apart from a largely dysfunctional executive operating between 1982 and 1986, Stormont would remain in mothballs until after the 1998 Belfast Agreement.

——— ———

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the coronavirus lockdowns having had a major impact on many of our advertisers — and consequently the revenue we receive — we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Subscribe to newsletter.co.uk and enjoy unlimited access to the best Northern Ireland and UK news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content.

Visit https://www.newsletter.co.uk/subscriptionsnow to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Ben Lowry, Editor