Inside the self-deception an unrepentant killer needs to stay sane – but at what price? Ex-UVF man Billy Hutchinson admits: My life is full of contradictions

What contorted complexity lies at the heart of Northern Ireland’s politics.

There is not only a macabre element to interviewing a killer about how they ended human life, but an inevitable insensitivity towards the relatives of his victims who may well read their words.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet each year carries away in death or dementia more of those most heavily involved in the Troubles, and with it the chance to unearth new insight into what they did, why they did it, why they gave it up, and to help future generations to comprehend the futility of it all.

Six years ago when I last interviewed Hutchinson, he defended what as a 19-year-old he and an accomplice had done, claiming that his murder of Edward Morgan and Michael Loughran helped prevent a united Ireland and insinuating that he had intelligence that they were not random innocent civilians (as said by the judge at his trial and as recorded by the bible of Troubles’ killings, Lost Lives) but linked to the IRA.

A cousin of the half-brothers who were slain by Hutchinson wrote movingly in response to that interview, recalling “the sobbing, the uncontrollable sobbing, of my father bent over his coffin, in front of thousands in a packed St Paul’s on the morning of the burial, that brought embarrassment to a selfish 12-year-old boy”.

Writing about Hutchinson, he said: “He’s still stuck in his world of victimhood as much as he was when he was jailed – with my father, a man proud of his WWII medals, in court to hear the self-pitying cry of ‘my only crime was loyality’. No Billy. It was murdering Catholics. For being Catholics.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHutchinson claimed he had been misquoted, but this newspaper published a transcript of his exact words.

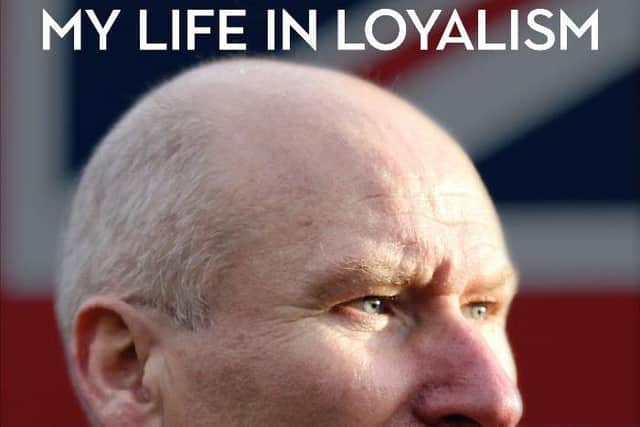

Even though he has a book to sell – My Life In Loyalism – I half-expected him to say no to an interview request. Instead, although knowing that hard questions were coming, unlike some politicians who run away from such situations he took question after question for well over an hour.

The first fact about the book points to how Northern Ireland has progressed. Hutchinson chose Gareth Mulvenna, an academic specialising in loyalist paramilitarism, to help write his memoir, which was published last week.

Mulvenna is a Catholic from North Belfast but that doesn’t bother Hutchinson, even though he accepts in the book that the UVF of which he was a key leader sought out random Catholic victims in the crude belief that this would weaken the IRA.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIndeed, he speaks with real conviction about Mulvenna’s professionalism and the rapport between them (“I liked his style, and I liked him as a person”). The academic makes clear in the preface that he is not endorsing all that Hutchinson has done, something the PUP leader says he asked him to include out of concern that Mulvenna would be professionally tainted by association with some of what he says in the book.

Hutchinson says: “In my view, if we’re going to move on it doesn’t matter what religion or what race somebody is – you want the best person to do the work”.

For those seeking hope, the fact that this ex-UVF leader seeks out a Catholic to help him write his memoir based on a judgement that he is the best person for the job encapsulates much about how Northern Ireland has progressed over the last half century.

It is a well-written book which conveys the mindset of the author. But it is riddled with questions that are not even asked, let alone answered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen those questions are at least partially answered in this interview, the answers say much about Hutchinson and the book would have better reflected the truth in all its unpleasant complexity had those issues been addressed head-on.

Hutchinson seems to hover between denial and cryptic acceptance that his position is constructed with the sort of logical weaknesses which render it an unstable habitation.

Nowhere does Hutchinson confront the enormity of what he did early that autumn morning in 1974.

Just four of 288 pages deal with the murders and trial for those murders which determined that 15 years of his life would be in the compounds of Long Kesh prison.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEven in those four pages, almost nothing is said about his victims. Hutchinson does show empathy for the impact of his actions on his parents: “I was full of bravado, perhaps...my mother [a strong unionist] remained stoic and didn’t directly address what I had been involved in, but my father [a socialist] was more to the point.

“He came to visit me and would ask, ‘Why did you get involved with this sort of thing?’...I think my father found it particularly difficult, as he had spent a lot of time in the company of Catholics, many of whom were good friends and work colleagues. I’m sure he must have worried about what they would think of him and the way he had raised his son.”

I ask him whether even now – as a man approaching his 65th birthday, when telling the story on his own terms and with no legal fear, given that he and his accomplice have already served their sentences – it is too uncomfortable for him to deal with.

“It’s not about being uncomfortable myself but I suppose in a sense it’s about other people that would have been involved on the periphery or wherever and I’ve always felt I need to be careful that I don’t create a jigsaw for the police to arrest them, so that’s why I did it [that way].

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It’s not about being uncomfortable about what I did, but it’s about protecting myself and protecting others”.

He goes on to offer another explanation: “I thought I could describe this very quickly and get it out of the way where it doesn’t cause problems for the victims’ families that are alive, or others”.

But that professed concern for his victims’ families sits uneasily with his continued public justification for their murders, something which Hutchinson must know will cause them pain.

One of the few things which Hutchinson does say about his victims in the book is that they had been identified by the UVF’s youth wing, the YCV, as “active republicans”, but he then adds: “How accurate the information was, I don’t know.”

Did he ever try to check the accuracy of the information?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Well, I had to accept the accuracy of it in terms of where it came from and things like that...I had the information, but I can’t stand over it to be 100%; it could have been 80%, it could have been 70% it could have been 98% – I don’t know. But the point is, you make a judgement call on the information that you’re given and in those situations you don’t really have an opportunity to – unless something looks really stupid – to actually challenge that to make sure what the accuracy was.”

The book is drenched in the sort of allegations familiar to anyone with even a superficial understanding of loyalism, the most significant of which is that senior unionist politicians not only whipped loyalists into an emotional frenzy, but actively urged them on behind the scenes while publicly condemning them.

But the book fails to deliver new evidence for his charges. It’s not that there is no evidence. It was known at the time, for instance, that in 1974 senior unionist politicians sat with UDA and UVF leaders to coordinate the Ulster Workers Council strike which brought down the power-sharing Stormont executive established by the Sunningdale Agreement – even though it was known that the groups had been involved in murder.

I put it to Hutchinson that there is scant evidence to back up his claims and he accepts that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen asked if he does have knowledge of politicians’ involvement with paramilitaries but does not want to reveal it now for legal or other concerns, or whether the absence of such evidence in the book is because he had no direct knowledge of what is said to have happened, he said: “Exactly. My knowledge was second hand”.

I put it to him that one of the themes which seems to permeate the book is that he was a creature of his circumstances and was more or less pushed towards paramilitarism and then murder, rather than that being something he chose.

He says that is an “excellent” summary, adding: “People talk about choice; not everybody has a choice.”

But he then goes on to somewhat contradict that, saying: “I’m not saying that everybody, including me, made the right decision at that time, but you have to make a decision.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet surely his argument is undermined by the fact that most of those with whom he grew up, with the same fear of the IRA as him, and who in some cases saw their relatives killed by republicans, chose to go a different route?

He partially accepts that, but contends: “If you do a survey of all those people, and ask them why they didn’t, I would guarantee you that most of them said ‘I couldn’t have done it’ – the difference is that you need to make up your mind whether you can do something or not”.

But rather than being cowards, does he understand that many of those individuals who shunned violence did so out of moral opposition to murder?

“People could have been morally opposed to it as well and anybody who was from a Christian family was certainly morally against it but there were also people who [did join paramilitaries]...they thought it was the morals of society that was allowing people to do what they were doing”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlluding to a belief in morality being relative rather than absolute, he says that the sudden escalation in murders in Northern Ireland during the Troubles was not because “we all woke up and wanted to be bad – no, we didn’t; people found themselves in circumstances and did some horrific things but they all have a story to tell”.

In the book, Hutchinson says that he had the view that “as a political prisoner I could not be rehabilitated as it was society that was wrong, not me”.

When asked if he still thinks that it was society at fault, rather than him, he says: “Yes, well society was wrong at that time and I think that has been changed because of the political process”.

The book deals in great detail with how as a schoolboy he entered gang life and eventually the UVF, but it does not address when he left the UVF – if indeed he did leave.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen asked about that, he is somewhat vague, saying that “it is evident that when you go to prison for a long time, when you get out the UVF aren’t really interested in you – maybe they’re not interested in you because you’re a risk”. He laughs briefly before adding: “I got involved in politics when I was in prison and when I got out I was working on cross-community work but I was also still working on politics...I didn’t go to UVF headquarters to get my P60 if that’s what you get.”

There is in the book a subtle linguistic contrast between how UVF and IRA actions are described. The IRA are said to be “murdering people”. I ask him if he would refer to UVF killings as murders.

He pauses momentarily before saying: “I don’t know why I used that word...but yes, the UVF did murder people. But I’m not so sure that I actually thought about using that word. It’s probably not a word I would have used normally.”

Similarly, Hutchinson recounts the poignant story of how 27-year-old Sergeant Michael Willetts of the Parachute Regiment stood in a doorway at Springfield Road police station to shield men, women and children being frantically evacuated while knowing that a bomb was in the room.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSgt Willetts was killed in the blast and the book records the words of the memorial to the young soldier which says that “his duty did not require him to enter the threatened area”.

Saying that he was moved by the soldier’s actions, Hutchinson then refers to him as having “shown extreme courage in protecting innocent people from terrorists”. Does he see what he and other UVF members did as terrorism? “Yeah, well you could argue about this and it’s for me a bit pedantic. I would say that we were counter-terrorists. Were we this, or were we that? We never saw ourselves as terrorists; that’s part of your psyche...I keep talking about using coping mechanisms and about having to hate the enemy and be all of those things and put them down.”

Then a chink open up as he goes on: “You will see people as terrorists; you will see them as bad people – even though you’re probably acting in the same vein and you’re probably just as bad as they are. But the point is you don’t allow yourself to think in those terms.”

The book does little to advance the argument for an amnesty in order to persuade former terrorists to tell the truth about what they did. Here there is no legal impediment to doing that, but Hutchinson provides an overwhelmingly self-serving justification of what he did.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen asked if he would say more under amnesty conditions, Hutchinson is coy, saying that “all the organisations should take corporate responsibility” rather than paramilitaries taking personal responsibility for helping their victims.

What of the future for Hutchinson? The PUP was in appalling shape when he took over as leader in 2011, polling just 3,858 votes in that year’s council elections. In the wake of the flag protests, that soared to 12,753 in 2014.

But the party has since atrophied and last year’s council election saw it poll just 5,338 votes – despite widespread dissatisfaction with the DUP.

If a future border poll saw a majority vote for a united Ireland, would he stay in Belfast?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYes, he says unequivocally, stressing that “we have to accept democracy”. He would stay “because I would want to make sure that I fought discrimination I know would come about [as a result]” before quickly adding that he would not be physically fighting.

Almost certainly, there would be some unionists and loyalists who in that situation would fight – even if they thought it futile. But he says they would need “to understand how much it costs to run a conflict against anybody...people need to be very, very careful about what they want and what they don’t want. I don’t want to live in a united Ireland and I think I’ll probably be dead before that decision is ever taken and I’m sure my daughter [now at university] will be a brave age”.

He says that unionism “needs to make sure that we make people feel comfortable in the UK – that’s everybody; not just a group of people who we think ‘oh, these are the people we like’ – everybody; all colours, all religions, all ethnicities”.

In a 1998 interview with The Irish Times, Hutchinson described himself thus: “Politically I am British, culturally I am Irish.” That is still his view and he recalls Irish dancing going on in unionist halls on the Shankill before the Troubles, and how “I wore a sprig of shamrock in my school jumper going to school every year when I was in primary school”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdComing back to the murders, does he at this point in his life have any regret about killing those two young men?

In a convoluted answer, he says that he “regrets the Troubles ever happened” and he “regrets all the deaths” – but beyond that generalised regret common to both loyalists and republicans he expresses no specific remorse for his actions that day. In other interviews he has straightforwardly said he justifies everything which he did.

I put it to him that surely as an intelligent man he can see a contradiction in that despite him having turned his back on violence and having been a firm opponent of loyalists returning to violence over recent years, even now when looking back from this late point of in his life he cannot say categorically that what he did was wrong – when even he that accepts he does not know if the two men he killed were involved in what he believed justified their death.

“Well, it depends what hilltop you’re on, but yes – if you’re not on my hilltop and you’re on someone else’s, certainly there’s a contradiction. I accept that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But my life’s full of contradictions. From my point of view...I talk about having coping mechanisms and I still use those to today. I am someone who doesn’t get close to people; I take them away...it’s how I’m wired.”

He goes on: “Until I die, I believe I’ll be wired that way; I’ll be wired to believe that what I was involved in was right; I’ll be wired to believe that to do that I had to actually have a way of life, I had to have a way of thinking – otherwise, you can’t get involved in this sort of stuff and not be affected by it so you need to make sure that you don’t allow your mental health to suffer.”

Then, referring to his day job as a community worker, he says: “And maybe I do this work as a sort of penance. I don’t know.” As with so many of Hutchinson’s answers, it appears to barely conceal a truth which he cannot speak, because penance is only done if the sinner accepts that they have sinned.

On the surface, Hutchinson is the archetypal loyalist hardman. But when facing the sort of obvious questions which he must have asked himself, this is a man who can see that he is riven with contradiction.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhy does any of this matter in 2020? Deconstructing the logic which still justifies driving up the Falls Road and murdering two Catholics is important not only because any justification for summarily taking human life needs to be interrogated, but because the history of Ireland suggests that in the right circumstances this behaviour may be repeated by another generation – on either side of the tribal divide.

And those who may consider such actions, should consider the aura of tragedy about Hutchinson. He says he does not want to be viewed as either a hero or a villain.

But there is an overwhelming sense from Hutchinson’s words that as he approaches retirement age, conscious self-deception is still the only way he can escape the lasting mental consequences of ending two young men’s lives that early morning in Belfast almost half a century ago.

* My Life In Loyalism is published by Merrion Press.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad——— ———

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers — and consequently the revenue we receive — we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSubscribe to newsletter.co.uk and enjoy unlimited access to the best Northern Ireland and UK news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.newsletter.co.uk/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Alistair Bushe

Editor