Russia's second revolution was all about Lenin, not the Bolsheviks

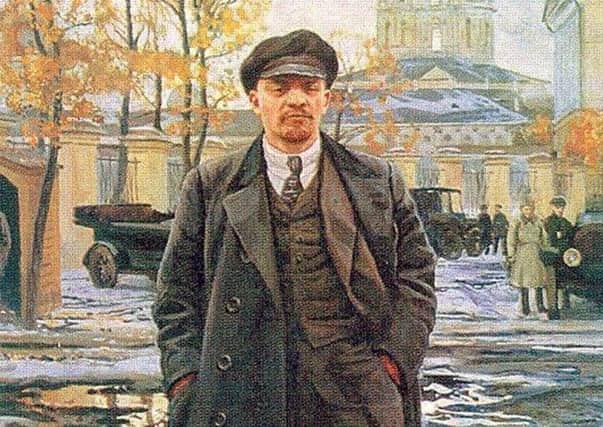

The Great October Socialist Revolution of 1917 is often referred to as the Bolshevik Revolution but actually it was Lenin’s revolution.

It was Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Lenin) who willed it and made it happen with little support from the Bolshevik leadership.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwo revolutions occurred in Russia in 1917, the first in February and the second in October; however, under the modern calendar, the latter has its centenary on November 7.

The February Revolution of 1917 deposed Tsar Nicholas II after more than 300 years of rule by the Romanov dynasty, ushering in a brief period in which hopes for a democratic future flourished.

Lenin’s Bolsheviks, a small, marginal faction of fanatics who were not taken seriously in the aftermath of the February uprising, took control in the October revolution.

Russian liberals and moderate socialists wanted a political revolution and in February 1917 that is essentially what they achieved.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe tsarist regime collapsed and with it, its supporting institutions: the bureaucracy, the police, the command structure of the army and navy, and even the Church.

However, radical or extreme socialists wanted a social revolution. Whereas for liberals – and moderate socialists – the ‘bourgeois-democratic’ February Revolution represented the end of the process, for more left-wing socialists it marked only a starting point.

Because the forces of liberalism and the middle classes were weak both numerically and politically, the ‘bourgeois-democratic’ revolution was not automatically doomed to failure but it was potentially vulnerable.

After the February Revolution there were two rival centres of political power in Petrograd (now St Petersburg): the Provisional Government and the Soviet.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe former was the embodiment of liberal and moderate socialist aspirations, the latter represented more extreme socialist opinion.

Although the Soviet frustrated the work of the Provisional Government at every turn, in retrospect the Soviet was remarkably timid but Lenin, the professional revolutionary and ideologue, was most emphatically not. He was determined to overthrow the Provisional Government.

He contended that Russia was passing from the first stage of revolution to its second stage. Because of the insufficient class consciousness and organisation of the proletariat, political power in the first stage of revolution resided with the bourgeoisie. To move on to the second stage power had to transferred into the hands of the urban proletariat and the poorest peasants.

The Germans had facilitated the return of Lenin from Switzerland to Petrograd in April 1917. They expected him to undermine Russia’s willingness to continue with the war and orchestrate Russia’s exit from it. In this Lenin surpassed their wildest expectations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Bolsheviks were not swept to power on a tide of popular support. On the contrary, the Great October Socialist Revolution was a coup d’etat masterminded by Lenin and supported by only a tiny minority of the population.

It was not even a Bolshevik revolution because hardly any of the Bolshevik leadership wanted it. It was Lenin’s revolution and without him it might never have happened.

The revolution was orchestrated from the Smolny Institute, Russia’s first educational establishment for girls, in Petrograd. The building was chosen by Lenin as the Bolshevik Party’s HQ.

Just before the revolution Lenin was stopped on his way there by police loyal to the Provisional Government but they mistook him for a harmless drunk and let him go. How different the course of history would have been if he had been arrested.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe popular perception of the Bolshevik revolution as a heroic fight by the masses owes more to John Reed’s ‘Ten Days That Shook the World’ (1920) and Sergei’s Eisenstein’s brilliant propaganda film ‘October’ (1927) than to historical fact.

The Bolshevik Revolution involved at most somewhere between 10,000 to 15,000 workers, soldiers and sailors – most of whom were surplus to requirement.

The cruiser Aurora fired a single blank shot. Theatres, restaurants and trams functioned much as normal as the Bolsheviks seized power.

The only damage to the Winter Palace was a chipped cornice and a shattered window on the third floor. It sustained greater damage during the filming of Eisenstein’s film than during the revolution.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInitially Lenin had at best a tenuous grip on Petrograd. The novelist Maxim Gorky thought the Bolsheviks would survive no longer than a fortnight but he underestimated Lenin’s ruthlessness.

In power Lenin moved rapidly to eliminate all opposition. He closed down the press and arrested the leaders of all the opposition parties. The prisons were soon so full of political prisoners that Lenin released criminals to make room.

He established the Cheka (Extraordinary Commission for Struggle against Counter-Revolution and Sabotage), the precursor of the KGB.

Lenin, who had nothing but contempt for democracy, ignored the results of the elections to the constitutional convention in which the Bolsheviks secured only 24% of the vote and closed down the assembly because he did not control it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe carried out a major distribution of land and the nationalisation of the banks and property.

An armistice was arranged between Russia and Germany and crippling peace terms were eventually agreed at Brest-Litovsk. According to the historian Orlando Figes, by the terms of the treaty Soviet Russia lost 34% of its population, 32% of its agricultural land, 54% of its industrial enterprises and 89% of its coalmines.

A ‘Red Terror’ was unleashed on the bourgeoisie which was denounced as ‘parasites’ and ‘enemies of the people’.

Gorky thought that Russia was reverting to medieval barbarism. In December 1917 Gorky claimed to have counted 10,000 cases of summary justice since the collapse of the old regime. Gorky concluded: ‘The Russian people, having won its freedom, is in its present form incapable of using it for its own good, only for its own harm and the harm of others.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA bloody civil war would follow between 1918 and 1921, and thereafter 70 more years of communist dictatorship.

On December 31, 1917 Leighton Rogers, a clerk in the Petrograd branch of the National City Bank of New York and an eyewitness to the events of 1917, observed that “the Bolsheviks have stolen the Russian Revolution and may endure”.

He continued: “I hope not, fervently, but it is a possibility that must be faced … the future in Russia is dreadful to contemplate.

“Not only is she out of the war [the First World War] but she is out of our world for a long time to come.”