Top tips for tip top calvings

Reasons for difficult calvings include both cow and calf factors.

About 80 percent of all calves lost at birth are anatomically normal. Most of them die because of injuries or suffocation resulting from difficult or delayed calving. Factors contributing to calving problems fall into three main categories — calf factors, cow factors and foetal position at birth.

Calf factors

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Heavy birth weights account for most of the problems related to the calf. Birth weights are influenced by breed of the sire, bull within a breed, sex of the calf, age of the cow and, to a slight degree, nutrition of the cow. Shape of the calf may also have a small effect on calving problems. Selecting bulls with low calf birth weight, shorter gestation length and good calving ease EBVs can help to reduce the overall number of difficult calvings.

Cow factors

Several factors associated with the cow influence dystocia (difficult birth), the major ones being her age and pelvic size.

Reducing dystocia rates through improved management

First-calving heifers require more assistance at calving than do cows, because they are usually structurally smaller. Therefore it is important to ensure target weights of minimum 65% of mature bodyweight at bulling and 85-90% of their mature weight at calving. Heifers should be weighed occasionally and diets adjusted to produce desired gains without making heifers too fat.

Heifers and cows with small pelvic areas are likely to require assistance at calving. However, even heifers with a large pelvic area sometimes require help delivering large calves.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFitter cows will have more fat around the birth canal, increasing calving difficulty. Therefore body condition scores (BCS) have to be managed throughout the year and cows should ideally be calved in BCS 2.5 to 3 for spring and autumn calving cows respectively.

The calf’s birth weight and cow’s pelvic area have a combined effect on dystocia. Calving problems could be reduced by decreasing birth weight through bull selection and/or increasing pelvic area by selecting the larger, more growthy heifers.

Foetal position at birth

Most calves are presented with the front feet first and the nose resting on the front legs.

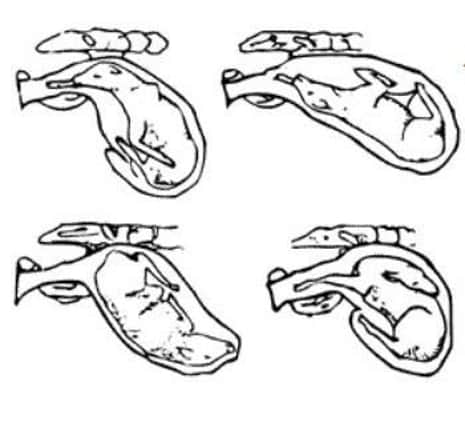

About five percent of the calves at birth are in abnormal positions, such as forelegs or head turned back, breech, rear-end position, sideways or rotated, etc. (Figure 1).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis requires the assistance from your vet or an experienced herdsman to position the foetus correctly prior to delivery. If foetal position cannot be corrected, your vet may have to perform a caesarean section.

During pregnancy, the foetal calf is normally on its back. Just prior to labour, it rotates to an upright position with its forelegs and head pointed toward the birth canal (figure 2).

Imminent parturition is indicated by separation from other cows in the group for up to 24 hours before calving, udder development, accumulation of colostrum, and slackening of the sacro-iliac ligaments which can easily be felt in between the tail head and the pin bones.

1. First stage labour

First stage labour is represented by dilation of the cervix (neck of the womb) which may take three to six hours. Any unusual disturbance or stress during this period, such as excitement, may inhibit the contractions and delay calving.

2. Second stage labour

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSecond stage labour is represented by expulsion of the calf, and takes from five minutes to several hours.

Delivery normally is completed in one hour or less in mature cows.

Proper judgement should be used so that assistance is neither too hasty, nor too slow. Intervention should be performed approximately two hours after the onset of stage 2, as defined by the appearance of the foetal hooves in the vulva. In herds where intervention is conducted less than one hour after the onset of stage two there was significantly higher use of a calving aid and incidence of downer cows. Thus the “two feet-two hours” rule of thumb has been adopted.

With the calf coming forwards, reasonable traction will deliver the calf when two people pulling can extend both front legs such that the fetlock joints protrude one hand’s breadth beyond the vulva within 10 minutes’ traction. Such movement of the calf’s forelegs represents extension of both elbow joints into the cow’s pelvis. Veterinary attention is necessary if greater traction is applied without obvious progress and the elbows are not extended easily.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf the calf is coming backwards and two strong people can extend both hocks more than one hand’s breadth beyond the cow’s vulva within 10 minutes pulling on calving ropes, further traction should deliver the calf safely.

Care has to be taken when using the calving aid as the maximum tractive force applied by a calf puller is approximately 400kg which is five times greater than that of one man pulling (75kg).

3. Third stage labour

Third stage labour is completed by expulsion of foetal membranes (afterbirth or cleansing) which usually occurs within two to three hours after birth of the calf.

Starting the calf

Whether the calves are assisted or not during calving and the degree of assistance will affect the new-born’s vigour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOnce delivered, clear any mucus from the calf’s mouth and throat with your hand. Then, if necessary, stimulate the calf to breathe either by rubbing it briskly, tickling the inside of the nostril with a straw or slapping it with the flat of the hand on the chest. Immediately after calving the calf should be briefly suspended upside down to drain the pulmonary fluids out of its lungs.

Artificial respiration can be applied to the calf as follows: place a short section of garden hose into one nostril, hold mouth and nostrils shut so air enters and leaves only through the hose, then alternately blow into the hose and allow expiration of air. Repeat at five to seven-second intervals until the calf begins to breathe.

Once the airways are cleared and breathing stimulation has commenced, the calf should be placed in sternal recumbence in the ‘dog sitting position’.

Finally, in order to make informed decisions on which cows to keep for the following year and how to breed them, keep some records in your calving book.

Make a simple table with six columns showing:

l Cow ID

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adl Date of calving. There is a tendency for later calving cows to have more difficulty.

l Sire of calf.

l Cow condition at calving. A simple F for fat, L for lean and A for average is sufficient.

l Age of cow.

l Sire of cow. This is particularly important in herds breeding their own replacements. Both Calving Ease Direct and Maternal/Daughter are important in determining how easily a cow will calve.