W B Yeats had only a marginal role in the evolution of Irish history and politics

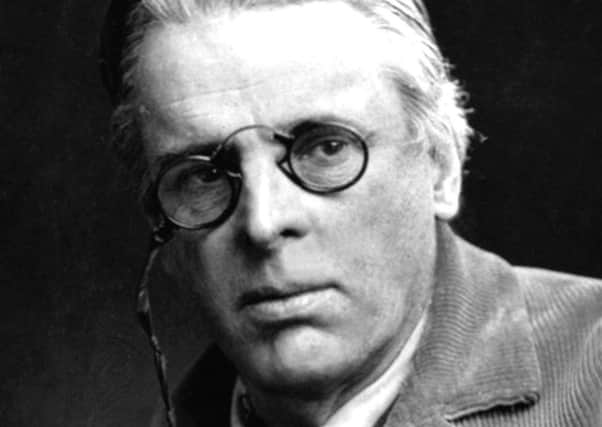

On his 70th birthday W B Yeats received congratulatory telegrams from around the world.

He was the guest of honour at a dinner at which the other guests included John Masefield, the Poet Laureate, who presented him with an original drawing by Dante Gabriel Rossetti on behalf of the writers and artists of England. Undoubtedly a pillar of both the British and Irish literary establishments, was Yeats the greatest poet of the 20th century?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are no objective criteria to determine such matters so ultimately it is down to a matter of taste and opinion. While T S Eliot regarded Yeats as the greatest poet of the 20th century, there are many who would award that accolade to Eliot himself.

Indeed the philosopher Roger Scruton has described T S Eliot, rather than Yeats, as ‘indisputably the greatest poet writing in English’ of that century.

It would be fair to observe that both Yeats and Eliot loom large in 20th-century poetry. W H Auden, too, would have his advocates.

Perhaps the Encyclopaedia Britannica judiciously covers the matter when it opines that ‘by the time of Eliot’s death in 1965 ... a convincing case could be made for the assertion that Auden was indeed Eliot’s successor, as Eliot had inherited sole claim to supremacy when Yeats died in 1939.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen T S Eliot described Yeats as ‘one of those few whose history is the history of their own time, who are a part of the consciousness of an age which cannot be understood without them’ he was making a much more interesting observation. It was a proposition with which Yeats himself would have immodestly concurred – as demonstrated by ‘Man and the Echo’ in which Yeats speculated: ‘Did that play of mine send out/Certain men the English shot?’

In his autobiographies Yeats provided further confirmation. Paul Muldoon, the Portadown-born poet, irreverently punctured this conceit by observing: ‘If Yeats had saved his pencil lead/Would certain men have stayed in bed?’

Yet it remains remarkable how many eminent historians and critics (for example, Conor Cruise O’Brien, Richard Ellman and George Dangerfield) have been willing to subscribe to T S Eliot’s thesis.

In 1999 Patrick Maume, in his The Long Gestation: Irish Nationalist Life 1891-1918, reproduces part of Yeats’ address on December 15 1923 to the Royal Swedish Academy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Nobel laureate claimed: ‘The modern literature of Ireland, and indeed all that stir of thought which prepared for the Anglo-Irish War, began when Parnell fell from power in 1891. A disillusioned and embittered Ireland turned away from parliamentary politics; an event was conceived and the race began, as I think, to be troubled by that event’s long gestation.’

As Maume demonstrates, this is not a thesis which survives detailed research or close scrutiny. Whatever Yeats’ merit as a poet, and his merits are considerable, his role in the evolution of Irish history and politics was fairly marginal.

Yeats’ famous speech on the subject of divorce – We … are no petty people. We are one of the great stocks of Europe …’ – in the Senate of the Irish Free State in 1925 also underscores his marginality.

First, no-one took his speech very seriously. Secondly, to what extent can Yeats be regarded as Anglo- Irish? The Anglo-Irish controlled the economic, political, social, and cultural life of Ireland between the 1690s and the Act of Union but Yeats did not possess the land or professional and social status requisite to be taken seriously as Anglo-Irish.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYeats did not even measure up to Brendan Behan’s yardstick of being ‘a Protestant with a horse’. If Yeats was Anglo-Irish, he was very marginal to Anglo-Irish society and if he was a snob, he had very little to be snobbish about.

Does Yeats as a poet have any relevance to the politics of contemporary Ireland? Yeats’ politics leave much to be desired but at various times since the late 1960s there have been naïve but well-meaning souls who really imagined they could transform the situation in Northern Ireland by quoting some lines from Yeats’ ‘Second Coming’:

‘Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.’

As Joseph Brodsky, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1987, shrewdly observed: “The only thing politics and poetry have in common is the letter ‘p’ and the letter ‘o’.” Pace, Shelley’s famous claim, poets are not ‘the unacknowledged legislators of the world’.

Admittedly, some poets have had the ability to speak to people of radically different political hues. Robert Burns in particular possesses this quality. The breadth of Burns’ appeal is genuinely extraordinary. It is a rare poet who can speak to the founding fathers of the Labour movement and to Tory Cabinet ministers, to unionists and nationalists, never mind hard-line communists and hard-nosed American plutocrats.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBurns’ appeal is most emphatically not political. He was never a rigorous or systematic political thinker. This is not intended as adverse criticism: most politicians are equally incapable of rigorous or systematic thought.

Burns’ great strength lay in his warmth, humanity and generous impulses. It was these qualities which appealed to Keir Hardie at the Labour Party conference in Belfast in January 1907 when Hardie told delegates that as members of the Labour Party they aspired to embody the principles of Burns in their daily lives and in their politics; and when they had achieved that, Burns’ ‘well-worn prayer’ would then be realised:

‘Then let us pray that come it may,

As come it will, for a’ that,

That man to man the world o’er

Shall brithers be for a’ that.’

And it was the same qualities which prompted Iain Macleod (‘A Very Liberal Tory’ according to his biographer Robert Shepherd) at the Tory Party conference in Brighton in October 1961 to quote ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ That’ and declare his belief in ‘the brotherhood of man’.