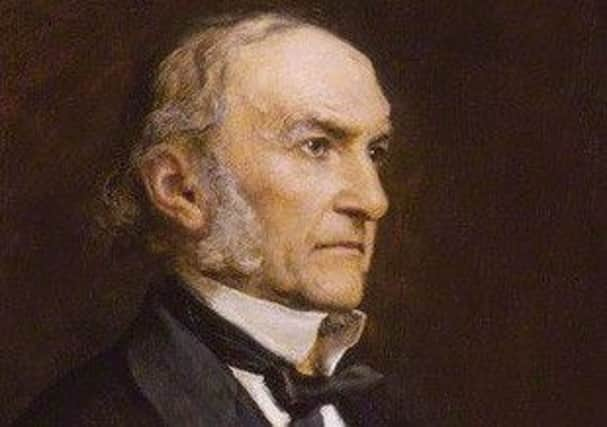

William Gladstone believed his mission as prime minister was to pacify Ireland

Liberal historians writing about W E Gladstone’s Irish policy tend to emphasise his insight and moral purpose whereas conservative historians focus on his political calculation and self-interest.

Thus A B Cooke and J R Vincent preface ‘The Governing Passion: Cabinet Government and Party Politics in Britain 1885-86’ with a quotation from ‘The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold’: ‘In a democracy,’ said Mr Pinfold with more weight than originality, ‘men do not seek authority so that they may impose a policy. They seek a policy so they may achieve authority.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe subtext is surely that Gladstone embraced Home Rule to achieve political power rather than he sought political power to implement Home Rule.

In the late 1860s virtually identical considerations were at play when Gladstone took up the cause of disestablishing the Church of Ireland as an electoral strategy to win political power. He deliberately placed disestablishment at the heart of his election campaign in November 1868 in order to unite the forces of English nonconformity, Scottish Presbyterianism and Irish Roman Catholicism to create a Liberal parliamentary majority.

It was probably the only issue capable of creating such an alliance and proved stunningly successful because his Liberal Party emerged with a majority of 112.

However, Gladstone managed to go down to spectacular defeat in his own South West Lancashire constituency because South West Lancashire was staunchly Orange/Protestant in sentiment and did not take kindly to the disestablishment of the Irish Church.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough defeated in South West Lancashire, he had also taken the precaution of contesting Greenwich where he was comfortably elected.

Early in December 1868, just before Gladstone became prime minister for the first time, he had been staying at Hawarden, his home in north Wales, cutting down a tree with an axe (his preferred form of exercise) when he received a telegram informing him of an imminent invitation from Queen Victoria to form an administration.

Opening the little buff envelope, his only response was ‘Very significant’ and he continued to attack the tree with gusto. Then he said, ‘My mission is to pacify Ireland.’

Ireland in 1868 was not conspicuously in need of pacification. The Fenian rebellions of February and March 1867 could be perfectly reasonably viewed as damp squibs. In April and May 1866 there had been mildly farcical (or ‘Ruritanian’ according to Roy Jenkins) Fenian invasions of Canada.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn September 1867 armed men had assisted in the escape of two Irish prisoners from a police van, killing a policeman in the process. In December 1868 Fenians had blown up the wall of Clerkenwell Prison and killed 12 people. Gladstone’s Irish policy was surely a disproportionate response to Fenianism.

The historian Vincent Comerford has even emphasised the social and recreational role of Fenianism rather than its nationalist commitment. Yet ‘to draw a line between the Fenians and the people of Ireland, and to make the people of Ireland indisposed to cross it’ provided Gladstone with a personally satisfying rationale for his Irish policy.

A few years before his death Gladstone speculated that, if providence had endowed him ‘with anything which could be called a striking gift’, it consisted of ‘an insight into the facts of particular eras, and their relations one to another, which generates in the mind a conviction that the materials exist for forming a public opinion, and for directing it to a particular end’.

He believed that he had experienced this ‘striking gift’ on four occasions. The first of these was the reintroduction of income tax in 1853; the second was his decision to disestablish the Irish Church; the third was his Home Rule bill in 1886; and the fourth was his wish for a general election in early 1894.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1838, as a young man (then ‘the rising hope of the stern unbending Tories’ and an Anglican evangelical) Gladstone had published ‘The State in its Relations with Church’ (in two volumes) in which he had defended the Established Church in England and Ireland.

In brief, Gladstone in 1838 contended that the Church possessed truth and the State was not morally neutral. Therefore the State had a duty to uphold moral good as revealed by the Church and that an Established Church was an essential part of national government. In Ireland it was irrelevant that a majority of the population did not subscribe to Anglicanism. Truth, not popular approval, was the justification of Establishment.

By the 1860s Gladstone was a Liberal and a High Church Anglican. He now produced a pamphlet entitled ‘A Chapter of Autobiography’ in which he repudiated his former views and sought to explain his remarkable volte face.

It is worth pointing out his interest in disestablishment was confined to Ireland. He was completely deaf to demands for the disestablishment of the Anglican Church in Wales (where Nonconformists constituted a majority of the population).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGladstone claimed that he had been ‘alive to the paradox‘ of the Irish Church’s huge endowments and its modest membership as early as the 1830s.

The 1861 census, the first reliable Irish religious census, revealed that the Church of Ireland had only 693,300 adherents and accounted for only 11.96 % of the population.

In embarking on the disestablishment of the Irish Church, Gladstone was setting out on a journey via the Land Acts of 1870 and 1881 and the Kilmainham treaty which would lead to his conversion to Home Rule in the early 1880s.

Gladstone was a compulsive diarist who used his birthdays as occasions on which to examine his life and take stock (as earnest evangelicals and High Churchmen did). On December 29 1868, his 59th birthday, he perceptively observed: ‘This birthday opens my 60th year. I descend the hill of life. It would be truer to say I ascend a steepening path with a burden of ever gathering weight. The Almighty seems to sustain me for some purpose of His own deeply unworthy as I know myself to be. Glory be to his name.’

Even he did not realise how steep the path would be or how heavy the burden.