The unlikely link between Halloween ghouls and World War One's flu pandemic

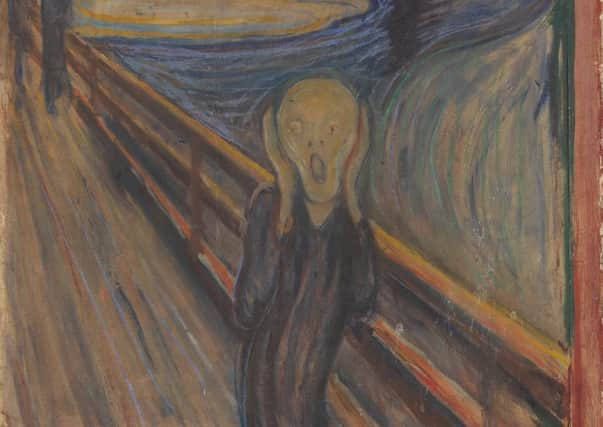

The mask is based on a painting called The Scream by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, said to be the second most famous image in art history, after Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

Munch painted a number of versions of his macabre, eerie-faced figure between 1893 and 1910.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStanding on a bridge beneath a swirling, blood-red sky, the figure is clasping its head in its hands, crying out in despair, with two other figures lurking in the vague mid-distance.

Munch, a troubled character with severe mental issues, was scarred by illness and the early deaths of his mother and sister.

He recounted his inspiration for The Scream in his diary in 1892, when he was out walking with two friends – “the sun was setting, suddenly the sky turned blood red. I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence - there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city. My friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety, and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature”.

The reason for mentioning Munch’s Scream here today, apart from its current links with Halloween, follows on from recent references on this page to the world-wide Spanish Flu pandemic that overshadowed the end of the First World War.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMore than a few News Letter readers shared Roamer’s bewilderment that the illness, which took the lives of between 50 and 100 million people, has apparently been ignored by history.

Over 800,000 caught the flu in Ireland and over 20,000 died.

It was sad to share Stephen Wallace’s e-mail here about his grandfather’s account of the Rea family from Moneymore – “the Spanish flu wiped out the mother and two or three daughters.”

And Selwyn Johnston shared other tragic accounts from Fivemiletown, Enniskillen and Clones where multiple deaths occurred in 1918 in more than a few homesteads, and schools and workhouses couldn’t function due to numerous fatalities and rampant, chronic sickness.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“No other epidemic or pandemic has claimed as many lives as the Spanish Flu, not even the Black Death in the 14th century or AIDS in the 20th century,” wrote Brooklyn-based medical historian Allison C Meier recently in a magazine article for funeral industry professionals, academics, and artists.

Meier continued: “One hundred years later, why have we forgotten the deadliest pandemic in history?”

“It could be considered the greatest catastrophe of all time.”

Irish historians Patricia Marsh and Ida Milne wrote in 20th Century Social Perspectives in 2009, also admitting – “remarkably, it has been mostly forgotten. In contrast to the worldwide large-scale commemoration and memorialisation of the First World War, there are no museums, heritage centres, exhibitions, national monuments or remembrance days dedicated to the pandemic”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCuriously, Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, painter of The Scream, is the exception!

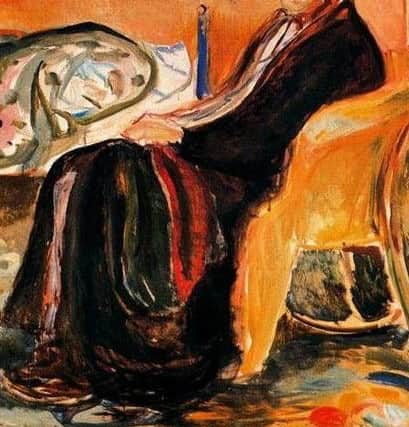

“Unlike the extensive cultural memory of the Great War, the Great Flu has barely had a passing mention in literature,” Marsh and Milne’s article continued, stressing, “Edvard Munch’s self-portrait is one of the few works of art on the subject.”

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George contracted the flu and like Munch, lived to tell the tale.

Other notable survivors included cartoonist Walt Disney, US President Woodrow Wilson, Mahatma Gandhi, Greta Garbo, and Kaiser Willhelm II of Germany.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAustrian painter Gustav Klimt, his protégé Egon Schiele, and French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, all contracted and died from the 1918 flu.

Groucho Marx, Haile Selassie, T S Eliot, Lillian Gish, Franz Kafka, D H Lawrence, Béla Bartók, Ezra Pound and Amelia Earhart all survived, but only Edvard Munch painted his ‘Self-Portrait after the Spanish Flu’ in 1919, in his dressing gown, within easy reach of his bed, haggard and pale-faced.

In ‘Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World’, author Laura Spinney notes that there are “very few cemeteries in the world that, assuming they are older than a century, don’t contain a cluster of graves from the autumn of 1918 – when the second and worst wave of the pandemic struck – and people’s memories reflect that. But there is no cenotaph, no monument in London, Moscow, or Washington, DC. The Spanish flu is remembered personally, not collectively.”

In another book about the pandemic and the search for the virus that caused it, author Gina Kolata described the horrible death it brought – “Your face turns a dark brownish purple. You start to cough up blood. Your feet turn black. Finally, as the end nears, you frantically gasp for breath. A blood-tinged saliva bubbles out of your mouth. You die – by drowning, actually – as your lungs fill with a reddish fluid.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA wide-ranging conference about the 1918-19 killer-pandemic (with speakers including Patricia Marsh and Ida Milne) was held earlier this week at Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery Museum, with an ongoing exhibition till next April, and there’ll be more on Roamer’s page between now and next month’s centenary of the Armistice.

Reader’s information is welcomed in my mailbox, and I’m looking forward to reading Ida Milne’s book Stacking the Coffins, about the epidemic in Ireland, including the intriguing theory that “political turmoil in Ireland during this period may also be a factor in its omission from Irish historiography”.