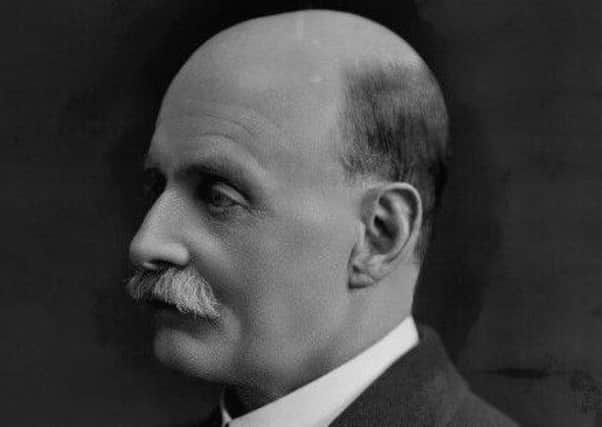

Walter Long, a hugely influential but little-known shaper of unionist and Irish affairs

On October 7 1919 prime minister Lloyd George established a Cabinet committee under the chairmanship of Walter Long to advise on Irish policy and to draft legislation which would become the Government of Ireland Act (1920). But who was Walter Long?

Born in Bath in 1854, Long was a member of a long-established Wiltshire landowning family with a parliamentary tradition stretching back to the reign of Henry V. He entered the House of Commons as a Conservative in 1880 and was an MP for 41 years, representing a wide variety of different constituencies, including South County Dublin between 1906 and January 1910. He was a Cabinet minister for 16 years. Apart from the 10 years of Liberal government from 1905 to 1915, he was continuously a Cabinet minister between 1895 and 1921.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBoth Long’s mother and wife were southern Irish unionists and were responsible for his life-long interest in Irish affairs and his enthusiasm for the unionist cause.

Significantly, he made his maiden speech on July 26 1880 during the third reading of the Compensation for Disturbances (Ireland) Bill. Although Long observed (on the day that Gladstone introduced the first Home Rule bill) that the great majority of English MPs, and Englishmen in general, ‘would be inclined to use strong language if they had been subjected to the same trials and tribulations as the Ulstermen had experienced of late’, Long’s connections were primarily with southern Irish unionism rather than Ulster unionism.

Between March and December 1905 Long was chief secretary for Ireland.

Prior to taking up the post, A J Balfour, the prime minister and leader of the Unionist Party, explained to Long that he wished him to bring the increasingly recalcitrant Ulster Unionist MPs back into line because George Wyndham, Long’s immediate predecessor, had comprehensively alienated them. Long swiftly managed to regain their confidence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLong lost his Bristol seat in the Liberal landslide of 1906 but was subsequently returned as MP for South County Dublin. Following the death of his friend Edward Saunderson on October 21 1906, Long became leader of the Irish Unionist Parliamentary Party on November 1 1906.

As an Englishman, Long may at first sight appear a curious choice to succeed Saunderson but it was a reflection of the esteem in which he was held by Irish unionists.

In the general election of January 1910, to the consternation of many Irish unionists, Long abandoned the ultra-marginal South County Dublin seat for the safe London constituency of the Strand, which had the added advantage of being conveniently close to Westminster.

When A J Balfour stepped down as leader of the Conservative Party in the autumn of 1911, most Irish unionists favoured Long rather than Austen Chamberlain when Sir Edward Carson indicated he was not in the running.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the event neither Chamberlain nor Long inherited Balfour’s mantle because Andrew Bonar Law emerged as an acceptable compromise candidate.

During the third Home rule crisis Long was more hardline in his unionism in private than he was in public. While Carson was prepared (for tactical reasons) to support the Agar-Robartes amendment to exclude Antrim, Armagh, Down and Londonderry from the operation of the third Home Rule bill, Long was adamant that the Agar-Robartes amendment was a trap designed to divide the forces of unionism and insisted that ‘as an Englishman connected by the closest ties with … Leinster and Munster’, he was not prepared to ‘sacrifice his friends there’.

This was only one of a number of occasions when Long sought to embarrass and to outflank Carson on the right. Another obvious example occurred in the summer of 1916. Much to Carson’s intense annoyance Long sabotaged Lloyd George’s attempt to ‘solve’ the Irish problem in the immediate aftermath of the Easter rebellion. Carson’s anger is evident in a letter to his wife: ‘The people who oppose this settlement don’t realise how hard we fought to get Ulster excluded and what an achievement it is to have got that’. Carson feared having to fight that battle all over again.

Long’s appointment to chair the Cabinet committee tasked to draft the Government of Ireland Bill came as a great surprise to him because of his life-long opposition to Home Rule and also to others.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLong’s committee proposed the establishment of Northern and Southern Irish parliaments, with a view to restructuring the whole of the United Kingdom on a quasi-federal basis, often inaccurately described before the war as ‘Home Rule all round’. Long favoured a nine-county Northern Parliament but James Craig’s insistence on a six-county Ulster prevailed at the last minute.

The views which Long held after the Great War were conspicuously different from his pre-war worldview. Before 1914 Long was unsympathetic to the ‘Home Rule all round’ but by 1918 ‘Home Rule all round’ had become his favoured option.

Up to at least the autumn of 1916 Long was a great champion of the southern unionist cause. Yet by January 1920 he was bitterly complaining about ‘the attitude of the [southern] Irish unionists, which consists of crying for the moon and appealing to us here [in England] to protect them from their local enemies’. He accused them of refusing ‘to face patent facts’ and ‘crying like spoilt children for that which they cannot get’. Ironically, Carson – despite his southern Irish birth, upbringing, family ties, education and early professional life – had sadly reached a broadly similar conclusion as early as the autumn of 1913.

How may we explain the change in Long’s worldview? The Great War, especially the death of his eldest son, Brigadier-General ‘Toby’ Long, in January 1917, went a long way towards undermining Long’s hitherto uncomplicated and straightforward unionism.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough Long was an influential voice in Irish affairs for several decades, drafting the Government of Ireland Bill was his last major contribution to Irish politics.

Raised to the peerage as Viscount Long of Wraxall, he died on September 26 1924. Few men can have been so influential in shaping Irish history and yet so quickly forgotten.