War memories of the tragic bombing of Belfast and provisions for child evacuees

Along with News Letter readers’ memories of children being evacuated to the country, and several Air Raid Precautions (ARP) handbooks that have arrived in Roamer’s mailbox, there have been a number of other interesting notes and emails about the blitz.

Please keep sending these wartime stories, accounts and reminiscences – they’re much appreciated and they’ll all be shared here.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

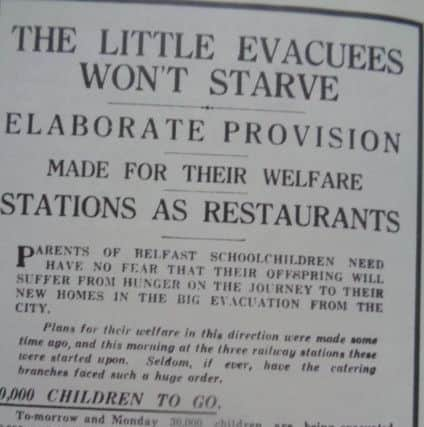

Hide AdMitchell Smyth has sent another poignant reminder of the traumas faced by the child-evacuees and their parents – a newspaper notice announcing that “elaborate provision” had been made for all the youngsters for the train journey “to their new homes in the big evacuation from the city”.

I couldn’t help but speculate on the provisions that might be offered to today’s young folk faced with similar circumstances!

Fizzy drinks instead of milk; burgers instead of ham sandwiches and even if barley sugar is still available would there be an outcry because there are no mobile phones or computer games on the list of rations?!

“We have in our possession a brass hand bell with the letters ARP on it,” began Jim Wallace’s email, adding: “When I stayed with my grandparents in the 1950s near the airport it sat on the hall table.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJim and his family have been wondering what the letters ARP stood for “and it was only reading your recent article in the News Letter that we realised it stands for Air Raid Precautions.”

Some details from two Second World War ARP booklets have been reproduced on this page, particularly about the precautions that should be taken when a family home was hit by a German incendiary bomb.

Jim Wallace’s mail ended “do you know any more about these ARP bells and you could enlighten us”?

I checked back on the little green ARP booklet number 8 – ‘The Duties of an Air Raid Warden’ – and discovered Jim’s bell on page 14, along with a wooden rattle and a whistle!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese were all put into action when there were “local gas warnings”.

If a gas bomb was dropped, or if the local gas supply was damaged by a bomb – there were various levels of ‘preliminary warnings’, ‘preliminary cautions’ and ‘action warnings’, all given by sirens – “either a fluctuating or warbling blast”.

Wooden rattles and whistles were used by wardens “to signal to anyone who remains out of doors and appears to ignore the sirens”.

According to the ARP Handbook, Jim’s handbell was a much more comforting sound – “the cancellation of the local gas warning will be by handbells, rung through the streets. Handbells may also be used to repeat the ‘raiders passed’ signal, but only if there’s no gas. Handbells will in fact be an ‘all clear’ signal.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnother reader’s email this week comes from Hugh McGrattan, about “the tragic events of Easter 1941, when Belfast suffered one of the most devastating air attacks on any British city outside London”.

The rest of today’s page is a compilation of extracts from Hugh’s email, which began by explaining that the severity of the attack “was the result of inadequate defence planning in the years preceding the Second World War”.

“Perhaps there was the forlorn hope that the Nazis would not risk sending their bombers so far to the west. As a result, the anti-aircraft guns defending Belfast and Londonderry were far too few in number and the Province was without radar stations or observer posts to give early warning of the approach of the enemy.”

“Although the Royal Air Force appears to have had little effect in stemming the hordes of Nazi bombers attacking Belfast, it should be remembered that the Province’s airborne defence consisted of a single Hurricane fighter squadron based at Aldergrove.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The dozen or so aircraft comprising No 245 Squadron had been sent to the Province from Turnhouse in Scotland the previous July, charged with the defence of Belfast and for convoy protection duties. However, it was not a night squadron and therefore was only fully operational under daylight conditions.”

“To make matters worse, when the entire telephone system was disabled in the raid of 15/16 April, co-ordination between land and air forces was lost and, although Hurricanes did take off, they could not be directed to where they were most needed.”

“However, the officer commanding 245, Squadron Leader J W C Simpson, DFC, did succeed in shooting down two of the intruders on other raids – a Heinkel 111 over Downpatrick on 8 April and a Junkers 88 near Ardglass on 6 May. He later shot down a Dornier near Stranraer when flying from Aldergrove and was awarded a bar to his DFC.”

“Squadron Leader Simpson survived the war with a total of 12 enemy aircraft destroyed. Tragically, he committed suicide in London in 1949.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The effect of the Belfast blitz was felt throughout the Province, of course, with substantial numbers of city people who had been bombed out of their homes seeking refuge in various parts of the Province. The pain of the deaths sustained in Belfast was also to be felt far beyond the city’s boundaries.”

There’ll be more from Hugh McGrattan’s very moving writings about the blitz, and other folks’ wartime memories, in the near future.