Anniversary date marks record-breaking result in history of Ireland and England

and live on Freeview channel 276

The match was something of a humiliation: beaten 0–13 by England. 667 matches later, it remains to this day Northern Ireland’s worst ever result (the Ireland team continuing today as Northern Ireland) and England’s best ever result.

Football was a young sport in Ireland at this time. Although the association code of football was being played by some in other parts of Ireland, it was only in Belfast and parts of Ulster that it had become properly organised through the formation of the Irish Football Association fifteen months previously. The IFA was small: in 1882, it only had thirteen member clubs, all in Ulster. In England, by contrast, the FA was in its nineteenth year, football had been experiencing a huge boom since the 1870s, and the international team had thirteen matches under its belt against Scotland and Wales.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first priorities of the IFA in its first season, 1880–81, were establishing itself as an effective governing and administrative body and organising the Irish Cup competition. In April 1881, however, the Association was invited to attend a conference in Manchester of the ‘kindred associations throughout the United Kingdom’ (the second such event, hosted by the Lancashire FA and including the English county associations as well as the national associations).

Amongst other business, the delegates to the conference agreed amongst themselves various inter-association fixtures, and the Irish delegate and IFA Treasurer, John Sinclair of the Knock club, returned home to Belfast with matches arranged against England and Wales for February of the following season. It was hoped that these matches would promote interest in the relatively new sport, and ‘stimulate the players to more assiduous practice’.

Organisation of the match began in December 1881. Following ‘lively conversation’ at the IFA Committee meeting on 5th December, it was resolved: ‘That the International Colours be Royal Blue Jersey and Hose and white Knickers,’ (the first-choice colours were not changed to green until 1931). Upon the shirt would be a ‘beautiful badge’ consisting of ‘an Irish cross, with harp in centre surrounded with a wreath of shamrocks’ and ‘embroidered with golden floss on a blue silk ground,’ designed by Committee member Mr McMillan of the Queen’s Island club.

At the next meeting on 22nd December, there was ‘an animated and lengthened discussion’ about who should be eligible to represent Ireland, the decision being that the qualification should be birth or seven years’ residence in Ireland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs preparation for the big day, the Association arranged a representative match at Cliftonville for a ‘Belfast and District’ team against an Ayrshire F.A. team on 21st January. Rather worryingly, the Belfast team lost to the Scots by twelve goals to nil. Next, the Committee asked member clubs to send in the names of players ‘competent for selection for a trial match on Saturday 11th February’ to enable the Association to select a team to play against England and Wales. The Committee selected eleven ‘Probables’ and eleven ‘Improbables’ for the trial match, to be played for an hour, after which the Committee would convene to select the international team, who would then immediately play a practice match against a ‘Scotch XI’ made up of Belfast-based Scottish footballers.

An offer from Knock of the use of their ground at Bloomfield for the international match and the trial was accepted. Only four of the humiliated Belfast and District team played in the trial, which the Improbables won by a single goal. A 1–4 defeat for the international team in the ensuing match against the local Scots didn’t bode well for the real thing in a week’s time.

Admission prices were set at sixpence for men, threepence for schoolboys and ladies free. A sub-committee was tasked with arranging the advertising of the match and the entertainment of the England party, while another was appointed to look after the ground arrangements. The Castle Restaurant in the newly opened Queen’s Arcade, Donegall Place, was selected to host the post-match dinner, the proprietor George Fisher submitting in advance a menu for approval costing four shillings and sixpence per head. The Irish players were charged five shillings each and required to pay in advance (whether attending or not). The extra sixpences would have helped allay the cost of the English party’s dinner.

Sinclair arranged with the Belfast & County Down Railway for special trains to be run between Queen’s Quay and Bloomfield on the day of the match.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe choice of Bloomfield as the venue prompted criticism from an anonymous correspondent to the Belfast News-Letter. The writer considered that the grounds at Cliftonville were ‘obviously more suitable and convenient’ than those at an ‘out-of-the-way place like Bloomfield’, and predicted that gate receipts would be disappointing as a result. This prompted two replies in defence of the chosen ground, noting the availability of public transport in the form of tramcars and trains.

The Bloomfield ground was a new one – it had been acquired by the Knock football and lacrosse clubs in May 1881 – but was very basic. It had a pavilion, but no stands or turnstiles, and the best view was apparently obtained from an adjacent railway embankment or the roadway. A contemporary account refers to it as being enclosed by a wire fence, and one from much later mentions a hedge. Its precise location is unclear, though we know that the entrance gate was beside Bloomfield railway station, which means it was on the south-eastern side of the Beersbridge Road, close to the Upper Newtownards Road. It was never used again as an international venue, the Ulster Cricket Ground at Ballynafeigh being the preferred choice for the next number of years. It hosted the 1883 Irish Cup final and a Charity Cup semi-final in 1884, but nothing of note after this. Its last use was by the Albion rugby club in the 1891–92 season before being built over.

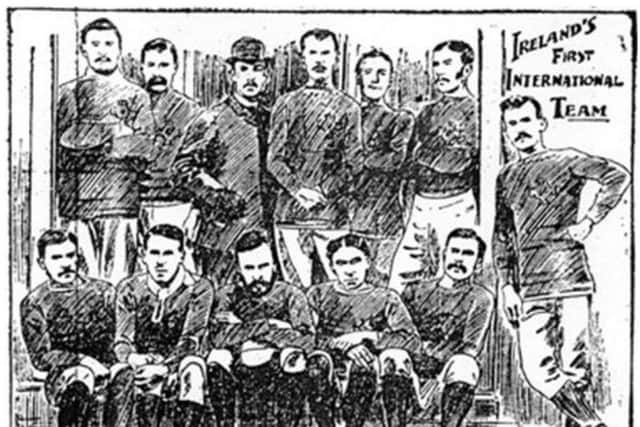

The chosen team had a very middle-class aspect. Of the eleven players given the honour of representing Ireland in this historic match, nine were from the professional and commercial classes, including an accountant, a doctor and a future Presbyterian minister.

Two of the team, however were working men. Rattray, a shipyard worker, and Johnston, a blacksmith, represented the future working-class character of football in Ireland. Johnston, at only fifteen years of age, remains the youngest ever person to represent Ireland or Northern Ireland. All eleven belonged to Belfast clubs: five from Knock, four from Cliftonville, one from Avoniel and one from Distillery. The team also featured three United Kingdom lacrosse internationals: Billy McWha, John Sinclair and Alex Dill.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe England team was made up of similar men. This was still the era of the gentleman amateur, though it was coming to an end (professionalism would be legalised in England in 1885), and eight of the team were former public schoolboys with current or future careers in business and the professions. Three, however, were from more modest backgrounds: Aston Villa’s Arthur Brown was an earring-maker and his club-mate Howard Vaughton a machinist, while Jimmy Brown of Blackburn Rovers, the son of a publican, was a solicitor’s clerk.

It was, however, a relatively inexperienced team at international level: seven of the team were making their debuts, while for two it was their second cap. The most experienced player was Charles Bambridge of the Swifts, who was making his fourth appearance, and who would go on to earn eighteen caps and score twelve goals. Jimmy Brown would captain the Blackburn Rovers team that won three successive FA Cups between 1884 and 1886.

The match kicked off at 2.45 in very unpleasant conditions, but nonetheless attracted an unquantified ‘large attendance’. Wind, rain and hail continued for the first fifteen minutes, before abating. Within that time, England – wearing white jerseys with the FA badge embroidered on the left breast – had scored three times, Vaughton getting the first goal after only three minutes. The improvement in the weather seemed to assist the Irish team a little: they managed some forays into English territory via the wings, and reduced the scoring rate so that England only managed another two goals before half-time. In the second half, however, matters only got worse and another eight goals were conceded as the English forwards ‘dribbled and passed in a specially clever manner’ and the Irish defence became demoralised. The speed of Bambridge, Jimmy Brown and Harry Cursham drew particular praise from the local reporter. And so it finished 13–0, the Aston Villa forwards Vaughton and Arthur Brown scoring respectively five goals and four goals each.

Of course, it was never expected that the Irish team, made up of relative novices, would pose any kind of serious challenge to the England team, but the magnitude of the defeat must have been dispiriting. While the backs, and in particular the goalkeeper, were criticised (the Sporting Gazette described them as ‘weak in the extreme’), there was some praise for the forward play of McWha and Jack Davison on the right wing. Of the defenders, Rattray, was considered to have done best and appears to have prevented an even greater score by clearing the goal line on more than one occasion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe post-match dinner, presided over by the IFA president Lord Spencer Chichester, came off successfully, after which the English team retired to the Queen’s Hotel, on the corner of York Street and Donegall Street.

A week later, the Irish team travelled to Wrexham to play Wales. Another heavy defeat ensued, though it was possible to discern improvement: the first ever Irish goal, scored by Sam Johnston, was an equaliser; the team was only 1–2 down at half-time; the five further goals conceded in the second-half collapse were blamed on the previous day’s rough passage across the Irish Sea; and Wales would go on to defeat England two weeks later. While it was an inauspicious start to international football, nonetheless Ireland now had its own team and would soon join the other home nations in the annual International Championship. In 1886, the IFA would become a founder member of the International Football Association Board, the body that continues today to write the rules of the world’s biggest sport and of which Northern Ireland remains a permanent member.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.