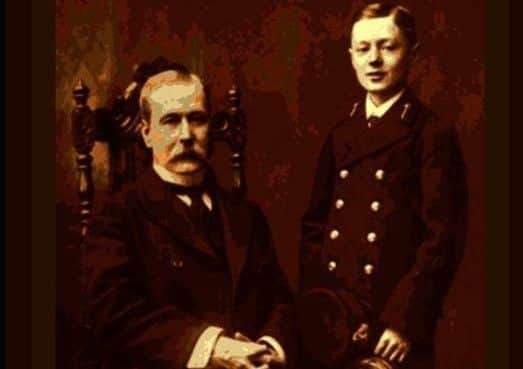

Edward Carson was the brilliant lawyer in remarkable real-life trial that inspired The Winslow Boy

Today Sir Edward Carson is remembered as the foremost opponent of Home Rule.

But before he became Ulster Unionist leader Carson established another reputation – that of the pre-eminent barrister of his time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe began as a Crown prosecutor in Ireland; having been called to the English bar after his election to Parliament in 1892, he became known as a defence counsel, acting for Lord Queensberry against Oscar Wilde’s suit for criminal libel and for Standard newspapers against the Cadbury brothers in another defamation case.

Courtroom success brought Carson wealth and its trappings: a house in Eaton Square, a mansion in Kent, holidays at fashionable continental spas.

Few of Carson’s cases show his abilities and character to better effect than his defence of George Archer-Shee between 1908 and 1910, an affair now most widely known as the basis for Terence Rattigan’s play (later twice filmed) ‘The Winslow Boy’.

In October 1908 George Archer-Shee was 13 and a new cadet at the Royal Naval College Osborne, a preparatory school for the senior establishment at Dartmouth; Osborne was housed in Queen Victoria’s sometime home on the Isle of Wight.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe boy was the only son by his second marriage of Martin Archer-Shee, agent for the Bank of England in Bristol. George’s grandfather was Sir Martin Archer-Shee, a Dublin-born Catholic who was a leading portraitists of the early nineteenth century, his sitters included William IV and Queen Victoria.

The boy’s half -brother was Major Martin Archer-Shee, a retired officer with a Boer War D.S.O.; he was also a Unionist (Conservative) parliamentary candidate who was elected to the Commons in 1910.

The Archer-Shees had stayed Catholic; before entering Osborne George had been at Stonyhurst, the Jesuit school.

On October 7 young Archer-Shee was permitted to visit a post office with another cadet. George wanted to buy a postal order for 15s 6d to buy a model train.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSoon afterwards it emerged that a P.O. for 5s had been stolen from another cadet, one Terence Back, and cashed.

George’s locker had been broken into along with Back’s. Archer-Shee was accused and an inquiry was held at which he was un-represented.

Thomas Gurrin, a handwriting expert, declared that Back’s signature on the stolen P.O. was in George’s hand; George, when asked to write Back’s name, produced a signature similar to that of the other boy.

The post mistress, Miss Tucker, stated that the stolen P.O. had been cashed by the same boy who bought one.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn October 17 Martin Archer-Shee was asked to remove his son; before his father could arrive two days later the boy was held for some hours under armed guard. His former headmaster at Stonyhurst declared he would be happy to receive George back.

The Archer-Shees wanted to see George vindicated; from the start Martin Archer-Shee was certain his son was innocent.

His older son suggested that his party colleague, Sir Edward Carson K.C., was “the one man to help us”.

On December 3 George was taken by his half-brother to see Carson. Carson asked to interview the boy alone.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMajor Archer-Shee could hear but not see his half-brother’s cross examination at the hands of a barrister who knew how to break witnesses down – Wilde having been but his most famous victim.

Carson made it clear that the older brother could not intervene; if he did, the case would be dropped.

The cross-examination lasted three hours; at its conclusion George Archer-Shee was in tears.

Carson’s purpose was not to be cruel; he wished to test both the boy’s resilience and his honesty.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThroughout George maintained his innocence and Carson, satisfied that he was not guilty, took on the case. In the opinion he wrote afterwards (now preserved in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland) Carson stated that he had seen nothing that would “lead me to the suspicion that he [George] was otherwise than an honest and truthful boy”.

He also identified at this early stage the important points in relation to the case.

He believed that the opposition’s evidence in the matter came down to two main pieces of evidence.

One was the allegation that the signature on the stolen P.O. was George’s. The other was the testimony of the post mistress regarding the two postal orders. Carson gave little weight to either.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFirst, the forger would evidently want to imitate Back’s signature. (Carson might have added that Gurrin, the supposed expert, had made mistakes before).

Second, Carson noted that while there was “no suggestion of want of veracity” on the part of the post mistress, she had not been able to identify George.

Carson noted further points in the boy’s favour.

At school and home his character had been irreproachable. He had no need to steal. George had had £ 1 7s in the hands of the Osborne paymaster and £4 3s 11d in the Post Office Savings Bank.

The person who had cashed the stolen P.O. had been given two half crowns but George had not used any half crowns to buy his P.O. or at any other time that day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was clear also that he did not know how to fill in a P.O.; on his own order he had signed in the payee’s section.

Furthermore he had never concealed his visit to the post office. In any case he had drawn 16s from the pay master to buy the P.O.

Carson took on the case but matters stalled. There were obstacles to progress.

George could not have a court martial as he only been a cadet. At length Carson found a solution.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe hit on the idea of using the procedure of a Petition of Right – a direct appeal to the Crown. This document was submitted in May 1909 and was duly endorsed “Let Right be Done”.

It took a further year for a first hearing to be held. In the meantime Carson, already an MP, became Ulster Unionist leader. The case was heard before Mr Justice Ridley on July 12 1910.

Sir Rufus Isaacs K.C., Solicitor-General (an office Carson once held), represented the Crown. Isaacs asked for the case to dropped as George had been in service of the Crown (despite the refusal of a court martial). His request was accepted and Carson stormed out.

Nevertheless leave to appeal was granted and the case was next heard by three Lords Justice of the superior court. This time Carson had his way and late in July a fresh trial commenced before Mr Justice Phillimore.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn his opening remarks at the trial, Edward Carson stressed that boys at Osborne were “mere children”.

Carson examined George Archer-Shee and his father. He also questioned Cadet Patrick Scholes who remembered that his friend had never spoken of cashing a Postal Order (P.O.), only of buying one.

Carson went on to cross-examine the Crown’s witnesses including Miss Tucker, the post mistress.

As Carson’s early biographer Edward Marjoribanks wrote, he “almost coaxed her into candour”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe damaged her evidence without impugning her honesty — just as his initial opinion had suggested.

Cadet Terence Back, the theft’s victim, admitted George had never seen the stolen P.O. before it was taken.

On July 29 Isaacs announced that the Crown was withdrawing the case, admitting also that George had neither stolen nor cashed the P.O. The previous day Isaacs and his junior had seen the Secretary to the Admiralty; they agreed that it would be better to abandon the case than to face an almost certain acquittal.

Carson, sentimental despite his adamantine reputation, cried. George had not been in court; he had overslept having been at the theatre the evening before.

After the case he saw Carson at the Courts of Justice.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCarson asked why he had not been too nervous to go the theatre. George answered:

“When I got into the court of law I knew I’d be all right. Why I never did the thing”.

Two days later Carson wrote to his confidante, Lady Londonderry. “It has been a great victory and I feel quite tearful over it.” He added that he had always been certain of the boy’s innocence – the more so because “of the blundering suggestions of the officers in charge”.

The Archer-Shee case displayed Carson’s great talents. He was no profound legal scholar but he had gifts of clarity of thought and expression in abundance. At the very start of his involvement he identified the main points of defence. He stuck to George’s side despite all difficulties.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor him the matter was not just a case but also a crusade. As Professor Alvin Jackson has written, the affair convinced Carson both of the bureaucratic tyranny of Asquith’s Liberal administration and of the possibility that such behaviour “might be overcome by moral strength and political persistence”.

It took another year for recompense to be made –something achieved only after the matter had been debated in the Commons. In the summer of 1911 George’s father was paid £7,210 in costs and compensation, much less than the £10,000 originally demanded.

Victory had been won but the rest of the story is inexpressibly sad.

George left Stonyhurst in 1912 but his father died the following year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEarly in 1914 George joined a Wall Street firm. Before leaving for New York he had been commissioned in the Army’s Special Reserve and when war came in August 1914 George was recalled. He left for England becoming a second lieutenant in the South Staffordshire Regiment.

By the last day of October 1914, as a Colonel Savage Armstrong later reported to the young man’s mother, George was in command of a platoon on an exposed section of the front line at Ypres.

Other units retired but Archer-Shee refused to move without express orders. His platoon retired only when such instructions came. George was the last to go.

The doggedness which had saved his reputation cost him his life: one of his men looked back to see George lying on the ground, his head facing the enemy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLater in 1914 Carson visited the War Office to ask after a nephew who had been reported dead. There he met George’s mother; she had just been told of her son’s death.

George’s body was never found; after the war his name was inscribed on the Menin Gate at Ypres.

Mrs Archer-Shee did not live to see either the peace or the memorial to her lost boy: she died in 1917, still only in her 40s.

Martin, George’s half brother, also served in the war, rising to lieutenant-colonel. He remained in the Commons until 1923 and was knighted that same year.

He died 12 years later.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe theft of a postal order for five shillings in October 1908 may have condemned George to an early death.

Had he stayed at Osborne going on to serve in the wartime Royal Navy, his life might have been less tragic. Service at sea in the Great War had its dangers but it was safer than the life of a subaltern on the Western Front. Of all groups in British service in that conflict, junior officers had the lowest life expectancy.

No culprit for the theft was ever found; none was ever sought. Had the police been involved at the start – their services were never requested – the truth might have been discovered at an early stage.

The damaged lockers and the stolen P.O. might have been examined for finger prints – a technique not used in Osborne’s own, flawed, investigation. Instead reliance was placed on a dubious handwriting expert and the uncertain memory of a post mistress.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThirty years after George died his story came to the notice of Terence Rattigan, a young playwright and wartime RAF officer. He wrote his play ‘The Winslow Boy’ as a version of the case. The play opened in 1946.

‘The Winslow Boy’ was a huge success both in the West End and on Broadway. Within 18 months theatre takings and the sale of film rights made Rattigan £65,000. A film version appeared in 1948. Fifty years on the play was adapted again for the cinema, this time by the American author David Mamet who has described ‘The Winslow Boy’ as “one of the most immaculately written texts in theatre history”.

The play differs from the original cases in a number of respects. The Winslows are prosperous but lack the connections of the Archer-Shee family; they are not Catholic; Sir Robert Morton, the play’s Carson, is not Irish; Morton is described as foppish and supercilious – qualities it would be hard to ascribe to Carson.

Great as ‘The Winslow Boy’ is it is hardly more interesting than the affair which was its inspiration; as is so often the case, the truth is no less enthralling than fiction.

• ‘The Winslow Boy’ is on at The Grand Opera House, Belfast, until tomorrow, Saturday night

• C D C Armstrong is a visiting research associate in history at Queen’s University