The EU misuse of the Belfast Agreement is the biggest threat to stability in Northern Ireland since 1998

The protocol forms part of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal agreement of October 2019, made with the European Union, followed by the free-trade agreement of December 2020 ... some two thousand pages drafted in Brussels, which restored national sovereignty at 23.00 (Greenwich mean time) on December 31 2020.

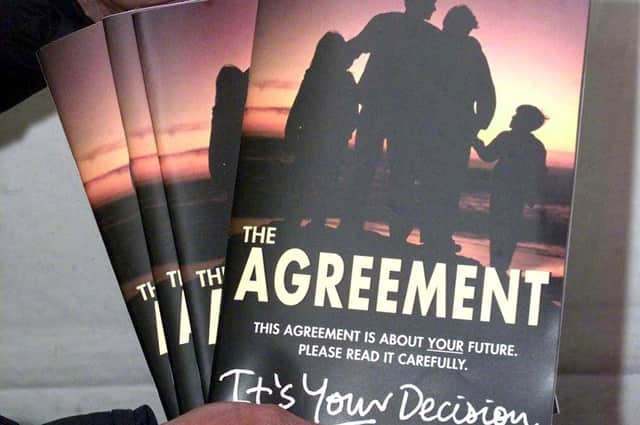

There will be reference in coming weeks and months to the 1998 Belfast Agreement, which ended the Troubles in Northern Ireland (‘NI’) after thirty years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIronically, while the EU was legally incorrect to play the Belfast Agreement card, after the 2016 Brexit referendum, the UK government is right to now follow suit — as Liz Truss did in the commons on May 17 2022 — given the east-west Irish sea border created by the protocol.

The Belfast Agreement is in fact two agreements: one, a short treaty between London and Dublin; and the other a multi-party agreement — neither of which is called the Good Friday Agreement!

Legal obligations and political aspirations interact in the related text of the two agreements.

The noun border appears nowhere in the Belfast Agreement, which left the international frontier between the two states expressly unchanged.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is because it was the 1986 Single European Act, which provided for the single — or internal (in EU terminology) — market.

At 23.00 on December 31 1992 (shortly after the Maastricht treaty), customs controls were removed by the EU on both sides of the Irish border.

I was one of those after the 2016 referendum who argued for a virtual border — advocating bilateralism between London and Dublin — to protect both the EU’s internal market and the UK’s single market while allowing trade (not that there was much) to continue flowing.

Bilateralism was legally arguable, because the Belfast Agreement had established the British-Irish intergovernmental conference: ‘The Conference will bring together the British and Irish Governments to promote bilateral co-operation at all levels on all matters of mutual interest within the competence of both Governments.’

All levels.

All matters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEnda Kenny (Taoiseach until June 2017) held to this position, until Leo Varadkar, his successor, took a EU-multilateral approach to Brexit. The Irish state finally admitted its destiny was EU dependency.

The two governments had a mutual interest in keeping a hard border out of Ireland, and it was practically doable. (The little-noted Irish walking away from the Belfast Agreement has been reciprocated by number 10: the Northern Ireland troubles [legacy and reconciliation] bill now before parliament was not negotiated with Dublin).

The economist Graham Gudgin has recently recalled the expert work done on an electronic Irish border, including by Lars Karlsson (former director of the world customs organisation in Brussels), the European parliament publishing his Smart Border 2.0 in November 2017 (Spiked, May 25 2022).

Michel Barnier — a Hibernophile French Gaullist — and his taskforce 50 within the commission adopted a nationalist interpretation (the Good Friday Agreement!) in the negotiations with the UK.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was to claim, in his Secret Brexit Diary: ‘My strategy has been to make sure that the British ... recognize their responsibility for the continuation of North-South cooperation in Ireland, set up under EU law, with EU funding, and supported by EU policies.’

This is simply untrue.

First, NI’s trade was substantially within the UK; a mere 5% of turnover went to the Republic of Ireland, and a further 3% to the rest of the EU.

Second, Barnier was generalising from a special EU programmes body to six later north-south implementation bodies.

And third, these bodies were — relatively small — bilateral international organisations, legally belonging to the two states.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNeither Theresa May as prime minister, Gavin Barwell her unlikely Sancho Panza nor (Sir) Olly Robbins stood up to this Brussels Behemoth on the Irish question. Their contribution – a major failure of statecraft – was acquiescing in the Irish backstop of unblessed memory. It took Boris Johnson, with Sir David (Lord) Frost, to replace the Irish backstop – related to a future trade agreement –with the NI protocol, followed by the trade and cooperation agreement without tariffs or quotas.

The October 2019 withdrawal agreement provided for an orderly withdrawal (which happened eventually) and legal certainty in the UK and EU afterwards, which shapes how we should interpret the NI protocol.

The protocol — with 19 articles and seven annexes amounting to 132 pages — is a drafting nightmare.

The UK has quit the EU, but it has left NI behind in the single market. The UK is recognised as a third county in the protocol, with its own customs territory, but the protocol scatters EU law (including customs but also regulation) across the province in five of the seven annexes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe real problem is governance, with the UK acting as agent of the EU – whether light-touch EU customs controls on east-west trade or heavy-handed tracking of every consignment? There are better ways of preventing British goods leaking across the Irish border into the EU.

The so-called Irish Sea border is an imagining of popular unionism, not its political leaders. Trade from Great Britain to NI has become constitutional. In February 2022, the first minister (Paul Givan) resigned over the protocol. The assembly did not come back after elections in May 2022.

The lesson from history is clear: the EU’s opportunist and confused use (with Irish support) of the Belfast Agreement – in order to shift customs functions from the Irish border to the Irish Sea — has led to the greatest challenge to stability and even peace in NI after 24 years.

Bien joué, Michel.

• Austen Morgan is a barrister and author of Pretence: why the United Kingdom needs a written constitution, to be published this September

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad• Ruth Dudley Edwards June 14: Boris has flaws but I still hope he’ll unlock protocol

• Peter Robinson June 14: DUP should stay out of Stormont until protocol bill is fully enacted

• Owen Polley June 13: Billy Bingham should have had a knighthood

• Ben Lowry June 11: BBC NI is downgrading its Twelfth output but pretending otherwise