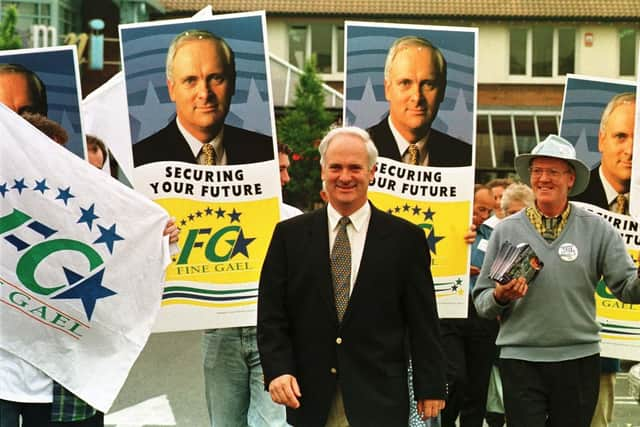

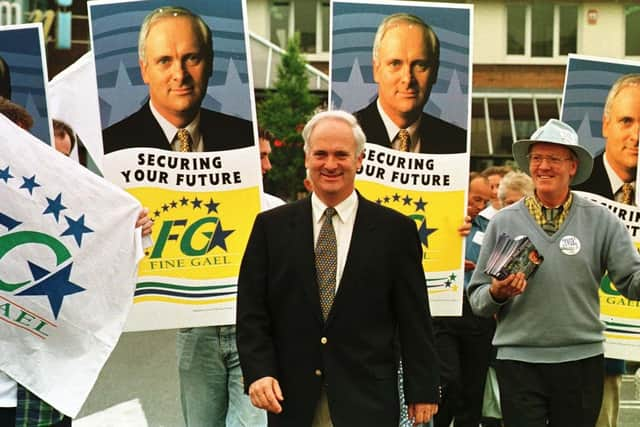

John Bruton: Former taoiseach has been remembered as 'the best friend unionists had for years' in the Irish government

and live on Freeview channel 276

The former taoiseach died, aged 76 in hospital in Dublin on Tuesday morning after a long battle with illness.

Mr Bruton took office as taoiseach in late 1994, two months after the UVF and UDA had joined with the IRA in declaring the first really major ceasefire of the Troubles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe headed a government comprised of his own party Fine Gael, plus Labour and the Democratic Left (the latter being a now-defunct Marxist-leaning party).

In February 1995, two months after taking power, he and the then-Prime Minister John Major published the "framework documents".

They set out a kind of roadmap for the peace process, and contained traces of what would later become the Good Friday Agreement.

In them, both governments stated their recognition of Northern Ireland's right to determine its own future, either in or out of the Union.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey said the Irish Government would "support proposals for change in the Irish Constitution" so that "no territorial claim of right to jurisdiction over Northern Ireland contrary to the will of a majority of its people is asserted".

Paul Bew says this was the first major hint that the Irish claim of dominion over Northern Ireland would be dropped – something which eventually took place by referendum in 1998 (with 94% of voters opting to drop the historic claim from the constitution).

Lord Bew, a historian and confidant of Lord Trimble, had met Mr Bruton a number of times.

He said the taoiseach had regarded "the territorial claim as ridiculous" and "radical republicanism" as "incoherent".

See also:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

Lord Bew said that his research had uncovered that Mr Bruton's ancestors in the Catholic Co Meath gentry had been pro-Union.

He also recalled that Mr Bruton had put a picture of constitutional nationalist John Redmond up in his office when taoiseach – a picture which his successor Bertie Ahern replaced with 1916 rebel Padraig Pearse.

Some nationalists had seen him as a "slobbering git" for welcoming then-Prince Charles to Ireland in 1995, and he was sometimes mockingly referred to as "John Unionist" by his more hardline detractors.

"[His] government did a lot to build up relations with the unionist community," said Lord Bew, who affectionately referred to him as 'The Brute'.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"He was always very sceptical of Fianna Fail. Always in a small way Anglophile. And Bruton strongly believed the Irish government should not be tribal in his attitude to the north.

"For a long, long time he was the best friend London or unionists in Belfast had in mainstream Irish politics.

"But Brexit did change that. He was a strong pro-European.

"He was ambassador for the EU in Washington DC [from 2004 to 2009] and he regarded Brexit – as many Irish people do – as not just wrong but more-or-less insane."

He also had "a pretty shrew eye for a horse"; for example Lord Bew recalls that Mr Bruton had predicted Hilary Clinton would fail in her 2007 bid to become US president, contrary to the expectations of many, including the UK Embassy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile Graham Gudgin, an advisor to David Trimble during his term as First Minister from 1998 to 2002, told the News Letter: "I have a high opinion of John Bruton.

"I think he was a fine taoiseach and a fair-minded man – and particularly fair on Northern Ireland.

"People in the south referred to him derisively as 'John Unionist'. But it wasn't that he was a unionist. He was a patriotic Irishman.

"He was fair-minded, highly intelligent, and always in my dealings with him polite.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I remember once he passed me in the Dail and said 'oh, hello Graham'.

"I thought: gosh, I haven't seen him for about three years, and he must meet tens of thousands of people. Yet he remembered, and was polite enough to say something.

"So I regret his passing and think it's a considerable loss to Ireland as a whole."

Irish state broadcaster RTE reports that he “detested the IRA’s use of violence and distrusted Sinn Fein – and he made little effort to hide his views,” adding that “Bruton’s dislike of Sinn Fein was fully reciprocated”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the IRA broke the ceasefire in 1996, “the resumption of violence proved that the IRA and Sinn Fein could not be trusted”.

He is survived by his wife, Finola, son Matthew and daughters Juliana, Emily and Mary-Elizabeth, grandchildren, sons-in-law, his brother, Richard, and sister, Mary, nieces, nephews, many cousins and extended family.