Lord Howell: After the Gerry Adams ruling, Parliament must act to reaffirm its clear, obvious and original intention on internment orders

In its recent judgment, R v Adams (Northern Ireland), the Supreme Court quashed Gerry Adams conviction for escaping from lawful custody.

The Supreme Court held that the interim custody order (ICO) made in relation to Mr Adams was not lawfully made.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe judgment records that the ICO was signed by a minister of state – but never says which minister of state — and says further that there was no evidence before the court that the secretary of state, Mr Whitelaw, had personally considered whether this ICO should be made.

It seems that the case was argued on the assumption that he had not been involved in the decision to detain Gerry Adams.

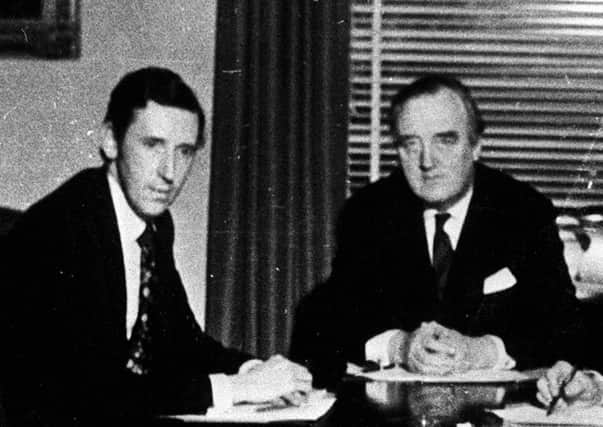

I do not know if my signature was on the ICO that was made in relation to Gerry Adams. It may have been. The Detention of Terrorists (Northern Ireland) Order 1972 came into force on 7 November and I served as one of the ministers of state for Northern Ireland from 26 March 1972 until 8 January 1974.

While I cannot speak with authority to the ICO that was made in relation to Mr Adams, I do have something to say about how the 1972 Order should have been interpreted and, especially, about the nature of ministerial government, both in general and in relation to the difficult circumstances of Northern Ireland in 1972-1974.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Supreme Court’s judgment seems to me, as Professor Richard Ekins and Sir Stephen Laws argue in their recent paper for Policy Exchange, to have badly misunderstood the nature and the practicalities of government.

Article 4(2) of the Detention of Terrorists (Northern Ireland) Order 1972 authorises a secretary of state, minister of state or under secretary of state to sign an ICO. As minister of state, I was one of the ministers authorised by that order to sign, and thus to make, ICOs.

The Supreme Court’s judgment does not say which minister of state signed the ICO in relation to Gerry Adams. As I say, it may be that my signature was on some of the ICOs made in this period, although they could have been signed by David Windlesham or Paul Channon.

Most likely, they would have been signed by David Windlesham as he was specifically assigned by Mr Whitelaw to oversee security issues, although we all worked together as a team on all aspects of Northern Ireland’s administration.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI note that it was David Windlesham who on 7 December 1972 moved the motion in the House of Lords that the 1972 Order be approved. He remarked then that “applications for interim custody orders are by no means automatically granted by the secretary of state.

There is a thorough process of scrutiny before he, or anyone on his behalf, decides whether or not to sign one at all.”

It is clear to me that the Supreme Court has misinterpreted the nature and scope of the 1972 Order.

The court misunderstands the significance of Article 4(2), which specifically provided for a minister of state or undersecretary of state to sign an ICO in the name of the secretary of state.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis provision was understood by government in making the order and in exercising it, and by Parliament in the debates about whether to approve the order, to authorise the minister of state or under secretary of state to decide whether an ICO should be made.

In so doing, we acted in the name of the secretary of state, who was responsible for the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) and the ministerial team and who was, of course, closely involved in many ICO decisions himself, as well as directing which ministers should oversee which aspects of Northern Ireland’s administration.

The fundamental failure of the Supreme Court’s judgment is its total misunderstanding of the nature of ministerial and departmental government and methods of operating.

A junior minister on duty at Stormont is in effect the persona of Her Majesty’s government and is thereby empowered to act for and as the secretary of state in the latter’s absence. And the secretary of state was often unavoidably absent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn relation to Northern Ireland, it was inherent in the nature of direct rule that the secretary of state had to be frequently in London – in Parliament or the cabinet – and that his responsibilities would often have to be exercised by a junior minister on the ground.

On the weekends, one of us was always the duty minister. One minister always had to be available to Parliament, including to answer urgent questions. And those of us who were members of the House of Commons had also to return to London frequently to vote (at one stage I crossed the Irish sea by air six times in a week!).

When the order was made, on 1 November 1972, and when it was approved by Parliament in December 1972, it was certainly contemplated that there would often be cases in which an ICO would need to be made by the minister of state or under secretary of state rather than by the secretary of state himself. The order clearly provides for this to happen.

The high number of ICOs that the government anticipated would have to be made, and were in practice made, also helps explain why the order provides that junior ministers may order temporary detention.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Supreme Court’s assertion that it would not have been difficult for the secretary of state to consider each case personally and to make each ICO himself simply does not match the reality.

As it happens, almost all signing of ICOs, where the actual signing of the document took place in Stormont Castle, was discussed directly with other ministers and usually with the secretary of state by telephone or message, if he had to be in London or his constituency home in Penrith.

The secretary of state could not always be directly involved and even when involved in some cases it would often be the minister of state or under secretary of state, in Stormont, who had reviewed the grounds for making an ICO in detail and who was satisfied that an ICO should be made.

The minister on duty in Stormont was fully entitled to act in the secretary of state’s name.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOther ministers were consulted, to the extent possible, not because this was what the law required, as if the junior minister were simply the mouthpiece of the secretary of state (SoS), but because that is how any team of ministers, operating as a team, would act in relation to important matters with political implications for which the secretary of state would have to accept constitutional responsibility.

In any case, in relation to Gerry Adams one can be absolutely sure that it would have been discussed most fully and confirmed by the secretary of state before the ICO was made.

The political salience and security implications of detaining Mr Adams would have made this unavoidable.

I do not know whether there is a record of the secretary of state’s involvement in this case or any other case in which his signature does not appear on the ICO itself.

The Supreme Court’s judgment implies not.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis may be unsurprising in view of how ICOs were often made, which is to say by a minister of state or under secretary of state in Stormont, with the secretary of state often consulted by message or telephone from London or Penrith, but without a record of that involvement necessarily being kept or now being available.

There would have been no reason, and perhaps no capacity, to record the secretary of state’s personal involvement, save in those cases where he himself signed the ICO, because Article 4(2) authorised the minister of state to sign the ICO and this signature had itself to be sufficient to authorise detention on the ground in Northern Ireland.

But it is a travesty to conclude that because ministers complied with the terms of the 1972 Order, and did not go above and beyond it to somehow record the secretary of state’s involvement, the ICO must now be quashed and the detention ruled unlawful.

It is quite startling to see the Supreme Court reasoning that the prosecution had failed in Gerry Adams’s case to prove that the secretary of state had personally authorised his detention.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe shape of the 1972 Order makes very clear that an ICO signed by a minister of state or snder secretary of state is the same as an ICO signed by the secretary of state himself and authorises detention.

It would have been utterly unworkable for the Royal Ulster Constabulary to have refused to detain suspected terrorists unless and until proof had been provided that an ICO signed by the minister had also been personally considered by the secretary of state.

Or for commissioners determining whether there should be continuing detention to have held that they did not have jurisdiction unless and until the secretary of state had provided evidence that he had personally considered whether to make the ICO in question.

This would have made the scheme of the 1972 Order simply unworkable.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Supreme Court’s reading of the 1972 Order was not what government intended, or understood, or what Parliament approved.

The whole point of the signature requirement in Article 4(2) is to make clear who is authorised to make an ICO and thus whose signature on the face of an ICO makes it lawful to detain the person in question.

The making of ICOs in 1972-1974, which the Supreme Court has now denounced as unlawful, was entirely in line with the law, with the wishes of Parliament, with normal ministerial practice and with the immediate security needs of protecting the public from acts of appalling violence and bloodshed (too many to enumerate).

Like Professor Ekins and Sir Stephen, I take the case for legislation to overturn the effect of the Supreme Court’s judgment – to make clear that ICOs signed by a minister of state or under secretary of state were lawful — to be overwhelming.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn so legislating, Parliament would be reaffirming its clear, obvious and original intentions and the absolutely normal practices of departmental governance and ministerial responsibility.

• Lord Howell of Guildford is the last surviving member of the ministerial team in the Northern Ireland Office, with responsibility under the Detention of Terrorists (Northern Ireland) Order 1972. He served as minister of state for Northern Ireland from 1972-1974 and as secretary of state for Energy and then for Transport under Margaret Thatcher. He was elected to the House of Commons as an MP in 1966 and has sat in the Lords as a Conservative Life peer since 1997. He was minister of state in the Foreign Office from 2010 to 2012

• Morning View: Lord Howell’s paper reiterates need for MPs to make clear the legal position on internment

• Other reactions to the Supreme Court ruling below

• Prof Ekins: A summary of the Policy Exchange paper

• Trevor Ringland: Supreme Court ruling on Adams walked on graves of judges murdered by IRA

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad• Jeffrey Dudgeon: Supreme Court ruling on Adams didn’t reflect violent context of the time

• Brian John Spencer: If we are to stop the rewriting of history, we need to say what IRA did during internment

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad• Kenny Donaldson: Victims of terror are dismayed by the Supreme Court ruling

——— ———

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Subscribe to newsletter.co.uk and enjoy unlimited access to the best Northern Ireland and UK news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.newsletter.co.uk/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Alistair Bushe

Editor