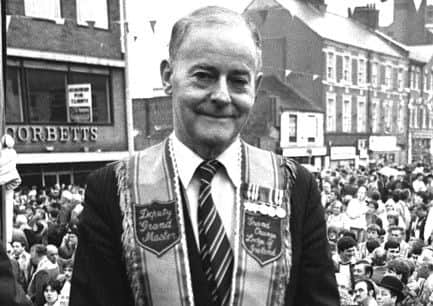

OBITUARY: Molyneaux – an outspoken and passionate unionist

He led the party from 1979 until 1995, having steered the Unionists through one of the most difficult and tumultuous periods in the history of the Province.

Like all politicians in Ulster, he lived in constant fear of the assassin’s bullet. He survived two INLA attempts in one day to murder him in October 1982 when he was elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut he was a courageous and persistent debater and was never afraid to criticise even those on his own side of the “Irish argument” if he felt they were falling short of the Unionist principles which he promoted with such conviction, commitment and fervour.

Nor did he allow himself to be overshadowed as the party leader when Enoch Powell was an Ulster Unionist colleague of his in the House of Commons. He certainly did not become - nor was any attempt made that he should become - a puppet on Enoch Powell’s string.

And although sometimes by sheer force of personality and rant, he was eclipsed by Dr Ian Paisley, the Democratic Unionist leader, Mr Molyneaux was always his own man and in many ways a more effective politician than his more boisterous compatriot.

Molyneaux’s attachment to the concept of the Union with Great Britain was no less fervent than his opposition to integration with the Republic of Ireland was ferocious.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis toughness, some say his obduracy, was invariably more than a match for those, in Whitehall as well as in Stormont, who tried to budge him from his chosen course. They tried in vain.

James Henry Molyneaux, an unsung statesman, was born on August 27, 1920 in County Antrim, and educated at Aldergrove School - a Catholic school - in the same county. He served in the Royal Air Force in World War II and went ashore on D-day in Normandy in 1944.

Molyneaux developed into a traditional right-wing Orangeman. He represented South Antrim from 1970 to 1983 and the new seat of Lagan Valley from 1983 onwards. He was parliamentary leader of the Ulster Unionists from 1974, and leader of the party itself from 1979. He was a Northern Ireland Assemblyman for South Antrim from 1982 to 1986.

Like Dr Paisley, he was prepared to endorse civil disobedience in extreme circumstances, but preferred to act within the law and concentrate on legitimate political action.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut his overall suspicion was that Ulster would be cheerfully sold out to Dublin by the British government without a care in the world, had it not been for the deterrent effect of himself and the party he led.

He saw his role as that of a general with an army “that is not making anything much in terms of territorial gains but has the satisfaction of repulsing all attacks on the citadel”.

His opposition to the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement remained vitriolic, but he was a man who always played a waiting game.

He was a straightforward devolution-of-power-to-Ulster man, feeling sure this could provide the basis for reconciliation and goodwill between the nationalist and unionist communities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMolyneaux was “appalled” by the 1972 decision to abolish Stormont and impose direct rule, and a few years later proposed the step-by-step restoration of Stormont’s powers, starting with self-administration.

And it was in 1977 that the links with Dr Paisley began to be cut, first over Paisley’s alleged connections with the paramilitaries. Molyneaux also opposed the extreme Loyalist strike of that year.

Soon after this he began to show his irritation with the British government. He refused Mrs Thatcher’s invitation to a conference on Northern Ireland local government in 1979 and boycotted a constitutional conference the following year.

Then he attacked as a “monstrosity” the Thatcher-Garret FitzGerald Anglo-Irish inter-governmental council of 1981. Molyneaux’s party leadership came under threat at this time, because of the successes of Paisley’s Democratic Unionists. But terrier-like, Molyneaux clung on.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMolyneaux did not mince words about Jim Prior when he was Northern Ireland Secretary in 1983. He demanded the removal of this “pig-headed and stupid” minister.

As far back as that, Molyneaux was already criticising John Hume, the SDLP leader, for “grubbing around the back-streets of Belfast” to meet Gerry Adams, the Sinn Fein president. And he denounced the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement as a “sell-out”.

As a telling and risky protest against the Agreement, he and 14 other Unionists resigned from the Commons and fought by-elections. He and all but one other recaptured their seats. And in a further protest against the Agreement he led an illegal march through Belfast and was “hopping mad” when a well-wisher paid his fine to stop him going to jail.

Under his leadership the Ulster Unionists broke their traditional links with the Conservatives and during the Thatcher and Major regimes Molyneaux and his colleagues sat on the Opposition benches.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was highly sceptical of the Downing Street declaration, of December 1993, describing it as a “tortuously-worded statement with many contradictions”.

Two months later, after numerous demands by Sinn Fein for “clarification” of the declaration, Molyneaux claimed it was a failure, a message he was prepared to deliver “loud and clear” despite protestations to the contrary from Dublin and Whitehall.

But he was not dismissive about the IRA “cease-fire” of September 1994, although he remained cool about the possibility of all-party round-table talks “which accentuate differences instead of reconciling them”, he claimed.

And he said at that time he hoped to live and see “a people at ease with each other in an Ulster at ease with itself”. He became a life peer in 1997.

But he remained an optimist, leaning on Harold Macmillan’s working motto: “Quiet, calm deliberation disentangles every knot.”

Lord Molyneaux was unmarried.