Abercorn bomb 50th anniversary: George Jones was on stage when explosion ripped through venue

and live on Freeview channel 276

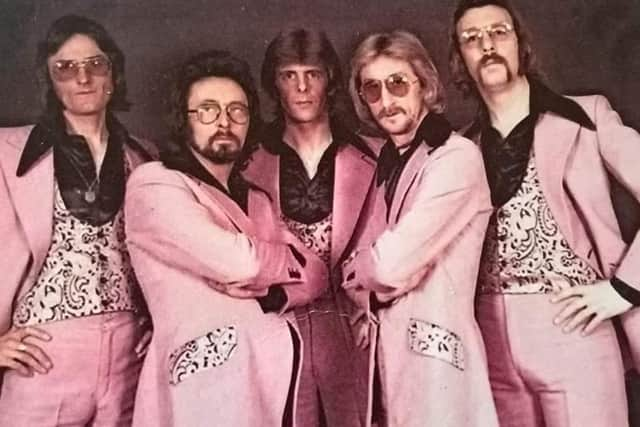

George’s band Clubsound were the houseband on the day of the IRA bombing, a day he said that he would never forget.

The 77-year-old, who was a familiar voice on the radio airwaves for decades, told the News Letter: “It never leaves me, psychologically you never forget it. Every time you’re down round that area it reminds you of it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When people talk about the Abercorn, you say, ‘I was playing the day the bomb went off’.

“It’s just always there, always with you, it’s imprinted on your brain.”

George said that Belfast was thriving in terms of cabaret clubs in the late 60s and early 70s: “At that particular stage there was 12 or 13 cabaret clubs, Belfast was buzzing in ‘68, ‘69.

“Dancing really came to a halt and cabaret took over, it was the big thing. All the bars were being extended to have stages or rooms for cabaret.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“All the acts were coming from England, from Australia, there were acts from Las Vegas coming over to us before they went to England. These 12 or 13 cabaret clubs were thriving in Belfast city centre, it was a wonderful collection of places for people who just wanted to go out and be entertained.

“It didn’t matter who you were sitting beside, what religion they were, you never really cared. At that stage, the Troubles were just kicking off. It was the heartbeat of the city at that time.

“There were still clubs for younger people like The Pound, they were able to do their thing. It was all happening, Belfast was thriving.”

He added: “I think it was the object of a certain branch of terrorists, they wanted to knock the heart out of the city by taking the entertainment centres out, that that would kill the city. It really did.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“A couple of places had been hit, but for some reason we thought we were immune.

“The Abercorn hit home the fact it was the first major bomb with fatalities in the city centre. People lost limbs, innocent girls had been killed, it was just a horrendous story.

“I know there were a lot more horrendous ones after that.”

Recalling the events of the day, he said: “In the Abercorn there was a wee one-staircase entry. There was an ex-boxer, big Terry Milligan, at the head of the stairs with my friend Trevor Kelly that day.

“Terry Milligan related to us before he died that he remembers them coming up the stairs and he was checking all their bags. There was a fella and girl came up and he wanted to look in their shopping bag, the guy wouldn’t let him. He said, ‘sorry, son I can’t let you in’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They walked down and seemed to turn in to the left into the restaurant. He reckons it was those two who planted the bomb. You imagine if that bomb had gotten upstairs with 250 people in there?”

Performing on stage when the bomb went off was Maxton G Beesley, whose son is the actor Max Beesley.

George said: “He was a great drummer and a brilliant impressionist. The whole week he’d been terrified, but as the week went on he’d relaxed and by Saturday afternoon he was brilliant.

“He was about 10 minutes into his act and ... that huge thud, the whole building shuddered. The next thing it was filling with what we thought was smoke.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I saw waiters flying through the air, bits of glass everywhere. That felt like it went on for a long time, it was probably only seconds, then it stopped and the alarm bells were going off, people were screaming.

“We had to try and get them out. I grabbed the microphone because the stage was the focal point, the lights on the stage were still on and we had an emergency door at the back.

“I tried to direct people out. We thought there was smoke from a fire but it was actually dust from about a five year old Guinness-sodden carpet.”

George said the carpet may have saved the people upstairs, and those downstairs from being crushed: “We were talking to some of the bomb guys about it, they said that the carpet actually took the impact.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It wasn’t a big bomb, it was meant to be put inside a large crowd, not to destroy a building but for some stupid or crazy reason it was meant to kill people.

“Subsequently when it went off down below it blew up through the floor, the carpet took the main impact which held the floor together really.

“They were saying, the bomb disposal guys, that if that had been only a few pounds heavier the whole floor would have come through, that’s 250 people you’re talking about. It doesn’t bear thinking about.

“Right at the very start of the Troubles it could have been the worst of the whole Troubles.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeorge remembers scrambling for a phone to call his wife before she heard the news on TV: “There were no mobile phones obviously, I wanted to get to my wife because they used to interrupt the programmes at that time to say ‘a bomb has gone off, would all key holders report back’. I didn’t want my wife to hear about the Abercorn and think the worst.

“I tried to get to a phone. The only phone was the paybox phone that was situated out in the foyer which was practically blown to bits.

“To get to the phone, I had to stand on the rafters. Looking down, that’s a sight I’ll never forget, the bodies and the mayhem down below in the restaurant.

“It was horrific. It brought home how serious this situation was and what it was going to turn out to be for years. The intent of the people who were planting these things, the value they put on human lives.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I never believed it would come to Northern Ireland or any part of Ireland that people would dream of doing this to innocent people.”

Clubsound called it a day in Northern Ireland soon after the Abercorn bomb.

George said: “Shortly after that, after a few more encounters with the Troubles with my family, we decided to pack up. We went to England, and then on to South Africa.

“We were looking for the promised land. They were crying out for English speaking acts in the holiday resorts like Durban. When we arrived we walked right into the middle of apartheid – we were going from one religious conflict into a race conflict.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It was a bad year. My young son nearly died of typhoid. My father died that year and I only got home an hour before the funeral.

“The bomb was the focal point, that’s what started it. I’ll never forget it.”

After the Abercorn bomb, owner Dermot O’Donnell, now deceased, was determined to reopen.

George said: “He was a great wee man, a great character, as all the bar and cabaret owners were.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It happened on the Saturday, he wanted to open again on the Monday. His intention was he wasn’t going to be beaten. I said, ‘Dermot, you have to think of the people who died and were injured’.

“He did get it all repaired and opened up about two or three weeks after that but it was never the same.”

Of the Abercorn bomb, George said: “It was one of the changes in my life that made me think more about my family – that this was going to be serious, these guys meant business.

“Anybody that would have had the heart to do that would have had the heart to do anything.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeorge said that having left Northern Ireland, the band eventually realised that by coming back to the Province they could actually have a part to play in helping people through the conflict.

He said: “After South Africa, we came back and we played right through the whole Troubles.

“The sad part about it was that people got hardened to it, they got used to it, they got on with it. Anybody outside Northern Ireland would never have understood this.

“When we came back we had a realisation that the humour that we were starting to develop, what James Young had been doing, the Ulster humour, a black humour, it kept people laughing during the dark days.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeorge said the launch of new trains by NIR in the 1970s meant people travelled to shows “no matter where the bombs were”.

He said: “We were packed every Thursday and Friday and Saturday. People had a yearning to escape. We gave them that opening to get away for the night.

“We felt we were doing something useful.”

——— ———

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers — and consequently the revenue we receive — we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSubscribe to newsletter.co.uk and enjoy unlimited access to the best Northern Ireland and UK news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.newsletter.co.uk/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Ben Lowry

Editor