Ulster-born sculptor carved her place in history with invention of plaster of Paris limb splints

Anne Crawford Acheson was born into a prominent Portadown Presbyterian family on August 5 1882 at Carrickblacker Avenue and was the second of the seven children of John and Harriet Acheson (née Glasgow).

Her father was a pharmacist and a partner in J & J Acheson (a linen firm with a factory on the Garvaghy Road), and later a JP. According to 1901 census he was vice-chairman of the Portadown Urban Council.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJoseph Acheson, her paternal grandfather had been the minister of Castlecaulfield Presbyterian Church. Her maternal grandfather, the Rev James Glasgow, was the Presbyterian Church in Ireland’s first missionary to India. A gifted linguist, he translated the Bible into Gujarati.

Harriet Acheson, her mother, was an accomplished poet and a formidably well educated woman.

Anne was educated at the Alexander School in Portadown and Victoria College in Belfast, where her mother had been both a pupil and teacher.

Like her mother, Anne too was an academic flyer. She studied at the Belfast School of Art from which she won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in Kensington, London where she studied sculpture under Edouard Lanteri from 1906 to 1910.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn completing her studies Anne toured northern Italy, visiting Rome, Assisi, Florence and Venice, prior to becoming a teacher in Putney in the autumn of 1910. When Acheson left Putney in 1913, she continued to take private pupils though she did not take up another teaching post. A year later, both Acheson’s parents died and Anne received a bequest of £3,000

Acheson began exhibiting her sculptures at the Royal Academy in 1913, when ‘The Pixie’ was accepted. From then until 1949 she exhibited 22 times, 30 works in all, with a mixture of statuettes, portrait heads and figurines for the garden. In the early years she worked in wood before turning to metal, stone and concrete.

She also exhibited at the Royal Hibernian Academy Annual Exhibitions in 1910 and 1914, the Annual Exhibitions of the Belfast Arts Society in 1926, 1927 and 1930 and the Ulster Academy of Arts in 1934, 1936, 1948, 1949 and 1950 as well as in other arts venues throughout the UK. She exhibited at the Paris Salon and in Rome, Brussels, Stockholm and Toronto.

She was one of the first women to become an associate member of the Royal Society of British Sculptors, the first woman full member in 1938 and a member of its Council in 1944. She received the Feodora Gleichen Memorial Award in 1938.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAmong other works, she was responsible for the portrait bust of the Gertrude Bell Memorial (designed by JM Wilson ARIBA), the original of which is in the National Museum in Baghdad. A truly astonishing woman, Gertrude Bell was a writer, traveller, political officer, administrator, spy and archaeologist, who played a significant role, for good or bad, in the creation of Iraq.

Acheson achieved success in the 1920s and 1930s as a sculptor of children, which had become fashionable among the well-off who wanted to immortalise their offspring.

The great majority of her works exhibited were garden or fountain figures under such titles as ‘The Imp’, ‘Water Baby’, ‘Watersprite’, ‘Mischief’ and ‘Boy with Puppy’. Acheson regarded playfulness as one of the requirements of garden sculpture but never descended to the mere quaintness. What precisely this means may be left to others to determine.

During the Great War Acheson had worked as a volunteer for the Surgical Requisites Association (SRA) at 17 Mulberry Walk in Chelsea.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a sculptor, Anne had a comprehensive appreciation of human anatomy and was fully conversant with how the human body moves. She developed arm cradles with the assistance of another sculptor, Elinor Hallé (whose father had founded the Hallé orchestra).

The cradles were made of papier maché (made from old sugar bags) soaked in a paste that could be easily moulded into shape.

Up to this point broken limbs had been roughly set using wooden splints.

These splints very often did not hold the bones in the correct position. As a result, the fracture healed badly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUsing a papier maché arm cradle made a significant difference to the healing process as it kept the bones in the right place.

Anne worked tirelessly to perfect her idea. Originally, the cradle was not made specifically for each patient, but Anne realised that it could be moulded to fit each unique fracture.

Patients who were able come to the SRA offices had their papier maché splint applied directly. Those patients who could not had plaster casts made of their limbs and then the papier maché splint was made in the plaster mould.

By 1917 it occurred to Anne that the plaster of paris that they had been using to create moulds for the papier maché would actually make for an even better splint.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor this important work she was awarded a CBE in 1919, as was Elinor Hallé.

During the Second World War Acheson retrained as a precision engineer and draftswoman to undertake voluntary work. She also worked for the Red Cross.

In the 1950s Acheson returned to live with her sisters in Glebe House, Glenavy, Co Antrim where she remained for the rest of her life. She died in Lagan Valley Hospital, Lisburn, on March 13 1962. She never married. According to Virginia Ironside, her great niece, she was ‘madly in love with someone in the [Great] War but he died’.

Although possessing an international reputation as a sculptor, until recently, Anne Crawford Acheson was a largely forgotten figure, not least in her native town. In 2010 David Llewellyn published a biographical study entitled ‘The First Lady of Mulberry Walk’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

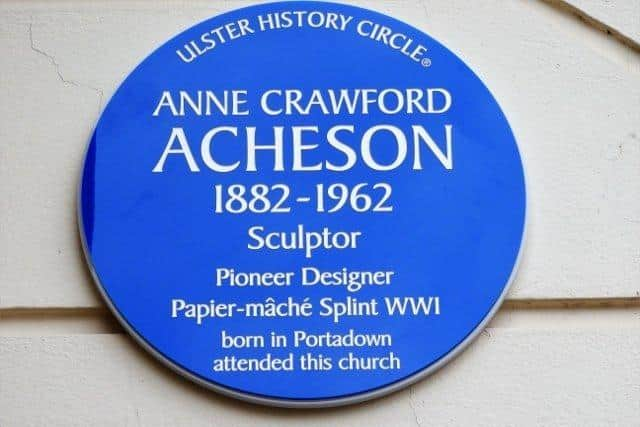

Hide AdIn October 2018 the Ulster History Circle erected a blue plaque at First Presbyterian Church, Bridge Street, Portadown, to commemorate her life and in May 2019 an exhibition entitled ‘Anne Acheson: A Sculptor in War and Peace’ was held in Millennium Court Arts Centre, Portadown. Belated recognition but welcome all the same.